Prasanna D Zore/Rediff.com reveals how the BMC has contained the spread of COVID-19 in Dharavi, India's largest slum, which WHO wants to know more about.

On July 7, Dharavi reported just one COVID-19 positive patient.

It was a significant achievement no doubt given the sheer scale of Dharavi's population and the abysmal living conditions posing severe challenges to hundreds of healthcare workers -- doctors, community workers, and paramedics -- that made this happen.

On May 3, India's largest slum cluster, with more than 750,000 people residing in cramped tenements, at places rising vertically up to four floors, had reported 94 patients.

For those oblivious to what Dharavi is all about, imagine a slum cluster spread over 2.5 sq km of prime real estate with 227,000 people crammed per sq km.

A slum where 80 per cent of the residents have to make do with 450 community toilets for their daily needs; where eight to 10 people live in space-starved eight by 10 sq feet tenements, without access to clean air or open breathing spaces just as they step out of their homes, and a place where most of the residents depend on outside food for want of adequate kitchen space or because most of the residents here are migrant labourers; a place where residents occupy the ground floor and about 1,500 single-room factories occupy the floors above them; a place that has 5,000 GST registered units and boasts of an annual turnover of over $1 billion.

That's Dharavi: A place that offers rozi-roti (livelihood) to lakhs of Mumbaikars; and against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, a place where social distancing and home quarantine is a practical nightmare.

It is in this situation, in a slum cluster as difficult as Dharavi, that the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai strategised, plannned and executed Mission Dharavi with solid support from hundreds of healthcare workers.

Doctors, voluntary medical healthcare givers, community workers toiled without much care for their own selves to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic that has now almost affected close to one million Indians.

Prasanna D Zore/Rediff.com spoke to doctors, community healthcare workers and volunteers working at Ground Zero to find out how the number of COVID-19 positive patients was brought down from 94 on May 3 to just one on July 7.

While the number of positive patients spiked thereafter -- about 23 were reported on July 15 -- after July 7, this story is about the ongoing efforts, in very difficult working conditions, to fight a novel virus that has brought the world to its knees.

The number of conversations with COVID-19 WARRIORS for this special report has been combined into the voice of one person. Every single person who spoke for this report began with: "This achievement is the effort of a committed team."

***

The beginnings

On July 7 we found two COVID-19 positive patients in Dharavi. But one of the patients' residential address was Dharavi as per his Aadhaar card. He lived somewhere else. That brought the figure to just one on July 7.

Before July 7, the figures kept fluctuating between five, eight and nine.

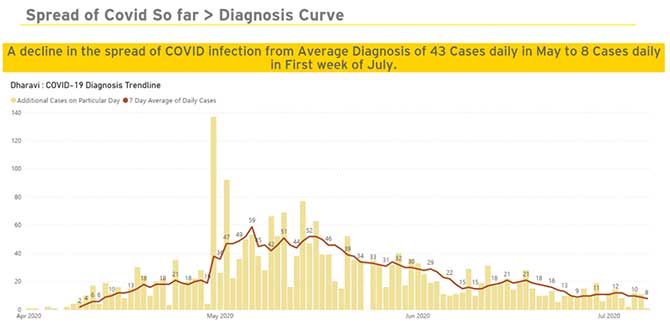

End of May and June first week (please see the images below) is when COVID-19 frontline warriors began to see a dramatic fall in the number of positive patients identified per day.

In the first week of May, the number of such patients kept fluctuating between the 50s and 80s. These were the figures only for Dharavi and not the entire G/North ward (Mumbai is divided into 24 such municipal wards).

In May the COVID-19 patients per day ranged between 94 on the maximum side and 18 on the minimum side.

It was in June that everybody began to see a huge ray of hope.

For the entire month, the number of patients maxed up to 43; it never went above this number.

And in the first few days of July, this number further fell down to under 20 every day.

For a few days in July we also had this number in single digits and that's when everybody realised that we can bring it down to one.

The two factors that made it possible

Of course, it is a team effort -- a massive one at that.

There are several highlights and several factors that worked together; one of them being our ability to forge public-private partnerships.

Initially, we had private doctors who did home-to-home screenings which led to a surge in identification of COVID-19 positive patients.

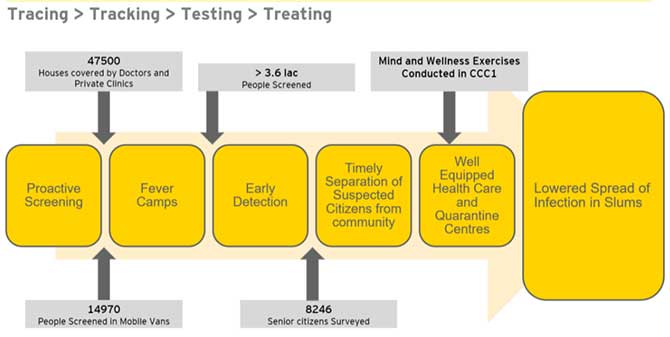

And it was, of course, the 4Ts: Tracing, tracking, testing and treating that just about sums up what this model can achieve.

Many more clusters like Dharavi are planning to follow the Dharavi model. Even WHO consultants are eager to know about the Dharavi model.

Tracing and tracking

Maximum identification of high-risk contacts and shifting them to quarantine centres played a big role in bringing down the number of positive patients gradually over a period of three months.

I remember the first case in Palika Nagar (a locality in Dharavi). We even managed to trace the milkman who would come to that society; the garbage collectors who visited the society; each and every person who came in contact with this first positive person in that society was traced, tracked and identified.

Every person who came in contact with this patient was treated as a high-risk contact.

Sometimes, many people who came into contact with a positive patient are neglected due to various reasons and they, in fact, act as spreaders.

Normally, everyone -- like the milkman or the garbage collector -- is not considered as a high-risk contact of the patient.

So, in effect, everybody who worked inside Dharavi was considered a high-risk contact, was traced and tracked. And, if that person turned out to be positive, was tested and treated.

Containing the chain: An illustration

Let me give you an example of a case where the man in the house worked in a garment factory. He would report to work every day even after the lockdown.

This was in the first week of May. Since his daughter had reported positive, we traced each and every garment worker and shifted them to the quarantine centre, even though this worker himself was not positive then.

But he was already a high-risk contact of his daughter and we decided to trace the high-risk contacts of the primary high-risk contact.

If any member of your family reports positive, then every member of your family who came in contact with this person will be treated as a high-risk contact.

Not just that, we also tracked and traced the people who came in contact with you or other members of your family.

That's how we managed to contain the chain of potential spreaders.

Screening the entire population; the risks at work

The other strategy that helped us achieve scale is we (the MCGM) went for public-private partnership.

General physicians, PMPs (private medical practitioners), and other doctors came on board voluntarily on an honorary basis.

These doctors actually went home-to-home for thermal screening (checking temperatures) and checking SPO2 (oxygen saturation) levels.

There were 24 doctors -- private practitioners -- who were accompanied by local health workers.

There were no BMC doctors because they were already stretched treating people at various COVID-only hospitals in Mumbai.

The screenings for temperatures and SPO2 levels was basically a special exercise for a special mission, Mission Dharavi, for which, these PMPs came together and actually screened the entire population of Dharavi phase-wise.

All the 24 private doctors did it on a voluntary basis, risking their lives for a noble cause. They would just get a bouquet or a rose at the end of the day, that's it!

In fact, four of them even tested positive. While four of them were treated successfully, one of them joined the fever clinics the very next day after his reports came out negative.

Wherever the doctors would go, a health supervisor and a number of health workers responsible for that particular area would accompany them. There were about 50 such health workers and 24 private medical practitioners, who were in the forefront of screenings in the biggest slum cluster.

These 74 people were actively involved in door-to-door screenings. Once their job was done and they had filed their reports for the day, the second rung of people got involved, which was the testing team.

The third T: Testing; in come the community health volunteers

The next day wherever we had the testing camp, those who were screened and had shown symptoms, would be referred to these testing camps. This team would make sure that they actually went there and submitted their swabs for testing.

This work was basically done by the community health volunteers who were given a list of people showing symptoms and were told that these people had to visit the testing camp and get tested without fail.

The community health volunteers would track these people and ensure they made it to the testing camps.

Once the reports came in after the tests were done, those who would test positive were taken to various isolation centres or to COVID-only hospitals depending upon their physical condition, co-morbidity levels, and other health parameters.

The clockwork

For testing we had hired Thyrocare (a private pathological laboratory that conducts COVID-19 tests). For testing we had not collaborated with any peripheral hospitals or BMC hospitals; we actually hired Thyrocare.

At these testing centres, we had three technicians: One for scanning their Aadhaar cards, one for filling the forms; the third person collected the patients' swabs.

Every day we had a fever clinic along with swab testings; swab testing camps happened at anywhere between two to six locations in Dharavi every day.

Every day at these swab collection centres, we would collect between 100 and 200 swabs and test them for the presence of coronavirus.

In the beginning even we didn't think this was possible. The general feeling was let's go cracking and see where we reach after three to six months.

We had a daily planning schedule according to which human resources were committed for performing various tasks.

We would minutely go through all pieces of data about the number of trackings done, number of people/contacts that were traced, number of people that had to be taken to the fever clinics or for swab testing, etc.

After such data was collated we would decide on the further course of action.

Every day at least one such camp was organised and depending on the data at hand we would also have three to four such camps every single day.

From March till the end of June we must have organised at least 400 such camps.

The day Dharavi reported just one COVID-19 positive patient on July 7, we had two such camps in which 78 swabs were collected.

And on July 6, we had collected swabs of 68 patients out of which just one patient tested positive on July 7.

Cutting down delays

With Thyrocare, if we collected the swabs today, we would get the result the next day.

In BMC-run or government hospitals, this time would be around 24 to 36 hours, given the scale that they have to handle, and so we decided to hire Thyrocare. With Thyrocare the turnaround time was drastically reduced.

If we took the swabs this evening between 10 am to 3 pm in our camps, then we would get the reports via mails by 5 am the next day.

Before we reached office, we would have the reports of people who tested positive on our tables and then the next leg of Mission Dharavi -- taking people to isolation centres, dedicated COVID healthcare centres and COVID-only hospitals -- would begin.

The testing times after the test reports come in

For every one lakh population we have one health post or aarogya kendra, which in rural areas are known as primary healthcare centres.

After the doctors complete their investigations by visiting homes or the factories of people who tested positive and after asking the patient about her/his travel history, the number of people s/he came in contact with to track and trace high-risk contacts, there is another team that takes these patients to various COVID centres and hospitals depending upon their medical conditions.

The final word

I would say we are not actually happy; in fact, we are a little tense and anxious wondering if this is really happening or it is just our imagination.

It is still unbelievable.

The second worry is if it is really happening, then we have a bigger challenge of sustaining this single-digit number (the numbers have since then again spiked).

Somewhere there is a sense of satisfaction that things are working out. But we still feel the pressure about sustaining this single-digit number.

We have a strong feeling that this trend will sustain.

Every day is a mighty challenge, but we are all committed to our jobs.

Bless us, bless the world, and pray that we get rid of this virus quickly by having a robust vaccine.