'It is the regional parties and their leaders who are the ones we have to watch.'

IMAGE: Congress national President Rahul Gandhi with Uday Shankar, now Chairman, Star & Disney India, left, and Ruchir Sharma, centre, in Pindra, Uttar Pradesh, at a 2017 rally. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ruchir Sharma via Penguin Random House India

This Lok Sabha election 900 million Indians will vote across 1 million polling stations.

They vote for 545 Lok Sabha seats and it takes 10 million election officials to handle the countrywide voting.

If one is even mildly curious, can one afford to stay away from viewing a stunning carnival of democracy like this? From understanding the world's greatest tribute to democracy?

It is a spectacle with a serious purpose, that finally, after six long weeks, gives, mostly without fail, India, a country with twice the population of Europe and as many languages, fairly and peacefully a new stable government that usually lasts its five-year term.

Ruchir Sharma, a senior investment banker at a top global investment firm in New York, whose first job was of a journalist, finds he can't ever keep away.

Every election season he shelves his voluminous financial reports, takes time off from work to head to India, the country of his birth, to cover something India does best: Vote.

How does he cover such an enormous country going to vote?

When on election tour, Sharma chooses his destinations carefully to make certain he comes away with the best flavour of the race. He often heads to Uttar Pradesh, the decider state with roughly 15 per cent of India's population and 80 Lok Sabha seats, that has turned out some of India's best known MPs, including Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi, Sonia Gandhi and her son Rahul Gandhi.

Sharma, the author of Democracy on the Road: A 25-year Journey Through India, is already in India for his 28th election odyssey.

After his Air India flight touched down in Delhi a few days ago, and he made his obligatory work trip to Mumbai, Sharma headed up to UP this time too. First stop: Lucknow.

Since it is difficult to get leave for the whole six weeks he had to forgo, he says ruefully, witnessing South India going to the polls. But he will head to eastern India and watch Bengalis cast their ballots.

"Despite all the advantages the ruling party may enjoy -- from much more money, much more sway over the media and clout over the business people -- the fact that the ruling party is always in danger of losing an election, shows me how vibrant democracy in India is, in a way that very few countries in the world can claim to be. That for me is really remarkable," Sharma tells Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel in the concluding segment of a two-part interview.

Do you think Rahul Gandhi is a leader to watch?

Rahul Gandhi, just by being the head of the Congress party, is a leader to watch.

We have seen Rahul Gandhi over the years and our first meetings that we had with him, obviously -- and I have documented in the book -- those were sort of abstract, academic kind of meetings, where he was going on about things, which we thought were not that relevant or sounded very academic. Over time, he seems to have changed.

I would say for me the real rise that we have seen in the 25 years watching election campaigns in India -- and they have become leaders to watch -- are the regional leaders. That's the real growth in India which is happening.

In India, a lot of focus and attention is paid to national parties. But both the national parties control half the vote. The other half is controlled by so many of these regional parties predominantly.

It is the regional parties and their leaders who are the ones we have to watch, whether it is in Andhra Pradesh like I have not seen much of Jagan Reddy (Andhra Pradesh politician Yeduguri Sandinti Jaganmohan Reddy).

Who is doing very well right now.

Exactly. So I think it is some of these regional leaders in general whether it is Akhilesh (Yadav, former UP CM) -- of course, Akhilesh we have watched many times -- to places in the South like Jagan Reddy or even people like (Tamil Nadu politician Muthuvel Karunanidhi) Stalin who we have seen only a few times, because in the past the entire focus in Tamil Nadu used to be on Jayalalitha and (former Tamil Nadu CM, Muthuvel) Karunanidhi.

So I would say it is those leaders who I would like to watch more now, because I think that's where the growth is happening.

What was the flavour of the places you were travelling through? Which were the places where you felt very at home at? Which state or which town has impressed you the most over repeated trips? And why?

One of the most memorable visits that I had on all these trips has been to Bihar. And one of the towns I remember most was Bettiah (north Bihar).

Image: Then Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi meets Ruchir Sharma's group in Rajkot in 2007. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ruchir Sharma via Penguin Random House India

The place with the horrible hotel?

Well, we stayed in many horrible hotels, but yes, Bettiah that Kishan Hotel was about as rough as it gets...

What I find very remarkable, like that entire trip I remember because it was this entire eerie feeling to be out there staying in a place which was not too far away from the Naxal hotbed at that point in time.

It was supposed to be, in those days, a completely lawless place. They wanted security guards to go with me when I went to that place. I would say Bettiah and that whole trip, which I describe in my book, where the only form of entertainment is one cinema showing films in Bhojpuri.

Like we drove to meet a landlord in the village of Dumaria. The 50 km journey from Bettiah to Dumaria I will never forget, because we were going through fields of elephant grass and sugarcane. By the light of the moon we could see these groups of women heading into the fields, working in teams, taking turns to relieve themselves, guarding against predators.

That entire trip, staying at Hotel Kishan, and that entire drive, and Bettiah, that has to be one of the most memorable trips we had....

That was the true backwater of India.

Any place that positively impressed you?

Bettiah in a way was not a negative impression. It was a sort of a very strong impression. It is a memory that is hard for you to forget

Positive is, like I have said, that when you get to see some of the hidden wonders of the world. I mention in the book how we were driving through Maharashtra. From Aurangabad we were going up to Akola and in the middle we came across the Lonar crater...

Hardly anyone knows even that such a significant crater exists out here. But for us to drive there and get to this Lonar crater, I think, was something which was great fun, in terms, of just discovering such an unexpected sight and how the locals have a different story of what caused the crater and there is a scientific reason to what caused the crater. That was one of those hidden discoveries.

Of course, we have been to such beautiful towns, along the way, obviously, like the likes of Jodhpur. I would say the drive from Pushkar to Jodhpur (Rajasthan) was one of the prettiest drives I have done anywhere in the world.

IMAGE: A meeting with Ashok Gehlot, now Rajasthan chief minister, at the Jai Mahal Hotel, Jaipur, in 2018. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ruchir Sharma via Penguin Random House India

What do you think Indian elections can teach the rest of the world? And what do you not get about the elections, even after 25 years of covering campaigns from a ringside kind of seat?

(Laughs) I would say in terms of what is remarkable about India for me is how elections now have become so fair and free of any violence. There is minimal violence compared to what could be there.

The rallies we go to, I always feel on the edge because there is hardly any proper crowd management technique and yet very rarely do you have any unfortunate incidents of stampede or the stage being broken and stuff.

So it is this organised chaos of India which I think is remarkable, which I think the rest of the world can learn from,)...

And also the fact also how deep the democratic impulses are in India. And I end on that in the book.

In a time when democracy is in retreat in many parts of the world, the fact that it is still thriving in India, shows how deep the democratic impulses are.

Despite all the advantages the ruling party may enjoy -- from much more money, much more sway over the media and clout over the business people -- the fact that the ruling party is always in danger of losing an election, shows me how vibrant democracy in India is, in a way that very few countries in the world can claim to be. That for me is really remarkable.

What I do feel we could do something about is this very long stretched out six week process of elections. I just feel that something needs to be done to shorten this time horizon.

I keep fearing what if you get another incident, like in 1991 where some major assassination happens, like Rajiv Gandhi's, all of sudden and half the country has already voted and the other half is voting with new information.

It is a very unfair way of having an election. I feel that the six week process of having elections is I think something we have to figure out.

You work in New York. So if you have to very briefly describe to people in America something about Indian elections, what do you say?

I think, stop thinking of India as one country.

Think of it much more like a European Union, where these 29 very different states of India, are all voting around the same time.

They have some national narrative, when it comes to big issues like national security. And the World Cup and stuff and cricket, where everyone comes together. Otherwise, the sub-national identities are very strong in India. I think this is a point which is very under appreciated by the outside world. Especially here (in New York).

IMAGE: Voters in Ahmedabad, India, April 2019. Photograph: Amit Dave/Reuters.

You used the term Un-Modi. I sense towards the end of the book you feel it is a toss up, on what India needs, between a strong leader and a more delegating leader. And you felt a strong leader wasn't that necessary.

There is this entire obsession in India, where (people feel) you necessarily need someone who is very strong (to run the country).

In India there is no one model that works. It is a country so diverse that different models work. At a state level you need strong leaders. But at a national level I feel more power needs to be given to the states because that's the only way to rule a diverse country.

I don't think it is a statement against Modi or against an Un-Modi. And Un-Modi that was my term for (former Madhya Pradesh CM) Shivraj Chauhan, someone like him is a very different personality as far as Modi is concerned...

My only (wish for) india is that it delegate as much power to the states as possible.

Modi used to speak about that when he first came to power as prime minister in 2014... and I wish he would go back to that mantra... because he understood that as a state chief minister.

As Gujarat chief minister and this is from some of the conversations we had with him, he was always upset by the amount of control Delhi had and the power Delhi would impose on states. He would speak about that.

Just a plea (to Modi) that 'You need to go back to that model, of delegating more power to the states, which you yourself used to speak about'.

That leads into my next question, which seems to the conclusion of your book that India would do well to listen to its states and allow its states and their CMs to rise and that might be the magic formula to India's progress?

How can any future PM, in your view, take this formula forward and allow the states to become much more powerful?

I think it is already happening. But it is (about) giving them much more power as far as economic decision making is concerned. So whether it is labour laws, land laws, just to sort of give them much more power to the states. That is what is required.

IMAGE: Ruchir Sharma's group meets then Congress president Sonia Gandhi at a rally in Patna, 2005. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ruchir Sharma via Penguin Random House India

You mentioned the maelstrom of caste, religion and socialism and its continuing effects on India. Is there anything good that can come out of caste and religion?

It is not about good. For me, this is the reality of India. What I say in the book is that these biases will fade over time as India becomes more urbanised.

The issue today is that India is still largely non-urban. Two-thirds of the population lives outside of truly urban areas. I would want some of these influences and effects to fade. But this will fade in influence over time. It is not going to happen just now.

For me, this is just the reality of India and there is no need for fighting against the reality of India.

What has your travels over 25 years shown, in your view -- in the most realistic view you can give -- about the popularity of Hindu nationalism and its ability to swing an election? Is it really part of India's DNA?

In the book I argue that the sub-national identities of India are strong.

Any nationalist movement has its limits. The idea of Hindu nationalism is very strong in the north -- in some of the north, and possibly some of the parts of the western belt of India.

But in places like the south of India, Hindu nationalism has virtually no appeal, in the way that it is perceived in the north. And in most parts of the east also I would say it doesn't have that much appeal.

I would say, as far as India is concerned, the sub-national identities, where most people think of themselves first in sub-national terms, the appeal of any nationalist movement is limited and the Hindu nationalist movement, in particular, is something which has echo in parts of north India.

But in south India, for example, the strain of Hinduism, even in a place like Tamil Nadu, which is deeply religious, there is no real pick up for the kind of nationalism that is practiced in the north.

So except for the north, the east, the south and even the west is fairly divorced from the idea of Hindu nationalism?

Ya. The south in particular and there are only pockets in the west and east which believe in it. The idea of Hindu nationalism, the way we think about it, has maximum echo in the north and in parts of the west.

IMAGE: Ruchir Sharma, centre, on the campaign trail in Chhapra, Bihar, in 2005. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ruchir Sharma via Penguin Random House India

Just like you said caste and religion is a sort of reality of India and we have to deal with it, so I think that is your reaction to dynastic politics? Dynastic politics does exist all over the world. Do you think it works for India and what do you think about it?

My favourite quote, which I use all the time, is the fact that politics is the downstream of culture. What it really means is that politics is a reflection and flows from the culture.

The family feeling and all that?

Exactly. Therefore in the book I have two statistics which sort of make this point really pop.

The one statistic which I say in the book is that two-thirds of the top 100 Indian private companies are family-owned.

And the other thing I find really remarkable is that if you look at the top 100 names on the Forbes billionaire list, 68 come from the mercantile castes like the banias, who are only one per cent of the national population.

This tells you about the fact that what is happening on the cultural aspect, which is in many ways reflected in the politics.

The fact that so many of Indian billionaires come from a few castes, that make up just one percent of the population, tells you something about the country.

Similarly when it comes to the dynastic rule as well. That is something that you see across the spectrum in India.

Congress leaders say the country will only accept the Gandhis as the head of their party, which could again be a downstream from what the culture is.

That is true of most regional parties in India.

It is true if you look inside the BJP. Apart from Modi, you have many other leaders in the BJP who sort of book their children as well for leadership roles.

Now whether it should be the Gandhis is a separate issue -- whether Rahul Gandhi is competent enough to lead the party is a separate issue for me. That's not what I am answering here.

Generally, dynasty and caste are reflected in any of the businesses which I find remarkable, in a way that few other countries are.

What were your great food experiences that you remember? I know you are vegetarian, but there can be great food experiences in India for vegetarians too.

Oh totally. This has been The Food Trail of India as well. We have had some of the most amazing meals.

I would say my best meal is having the Chettinad cuisine which is friendly for both vegetarians and non vegetarians in the area near Madurai. That area is (known) for Chettinad cuisine.

In fact, we were hosted there by one of the top business people in Madurai. Twice, we had breakfast at his home. For me, that was possibly the best meals I have had on the trip.

Chettinad cuisine and possibly having this Mughlai cuisine in Rampur in UP. Those have been a couple of the most memorable meals I have had on all my trips.

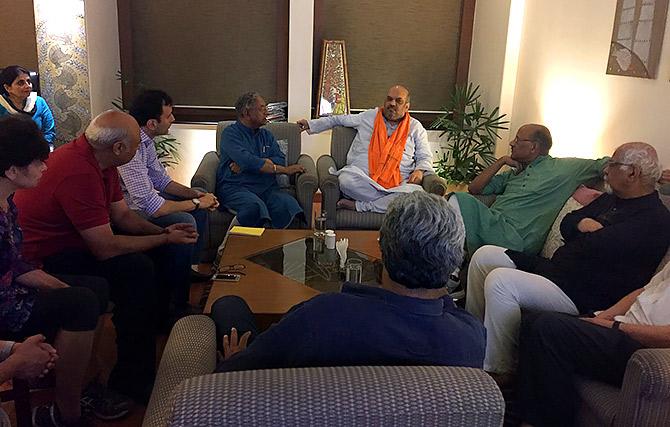

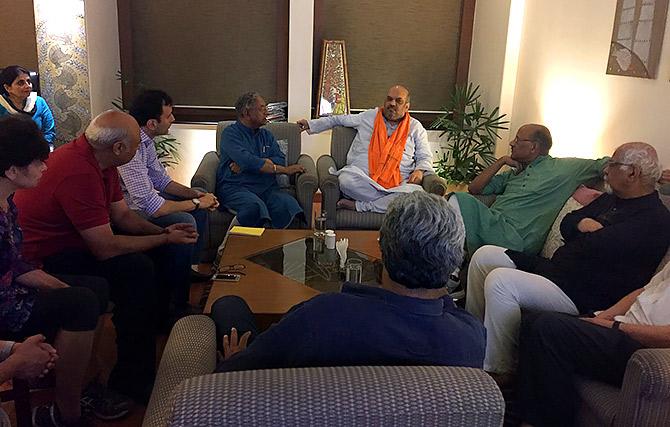

IMAGE: Ruchir Sharma and his group meet BJP national President Amit Anilchandra Shah in Patna in 2015. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ruchir Sharma via Penguin Random House India

Which states did you wish you had gone to? I was sort of waiting right through the book for Kerala to come.

We did go to Kerala briefly in the 2006 trip...

I think the states I have missed out are some in the east. Odisha and some of the north east states are obviously states that we missed out.

As I said there is no end to it right. Didn't have time. These trips are not over!

So you want to get there and you hope to get there?

Yes that's right. Still ongoing.

I wanted to know what you feel has been the secret of the south's success as compared to the north. Very often when you travel in the south you are quite taken aback by how much ahead it is. There is a huge contrast.

Do you think the secret has been that they started giving power to the lower castes early on, long before north India?

I hate giving generalisations... Some of the pecking order changes.

The south is generally more developed and cleaner. But the transformation that Bihar has had in the last 10 to 15 years has been quite remarkable.

On the other hand in Tamil Nadu you are seeing some regression out there, aren't we?. So I would say that is how it is. These things change. I don't think I would like to make a generalisation... I am averse to making these generalisations.

And the gap has been closing in recent years. That is something worth noting. The Bimaru states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, UP) have seen some of the fastest growth rates in the recent years, compared to the South, in fact, Bihar being a classic example. Even Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, you know their growth rates have been very rapid.

You spoke about India's thriving democracy. In your view what are the dangers that you perceive to India's thriving democracy? Anything that we should be worried about that might affect India's thriving democracy that we are so proud of?

We have to guard against this in terms of the fact we still want a free media, we still want our institutions to remain largely independent, whether it is the central bank or the Election Commission. So I think independence of the institutions and a free media, these pillars of democracy need to be protected.

That's something we absolutely need to look at because across the world these are the institutions that are coming under attack from the political class.