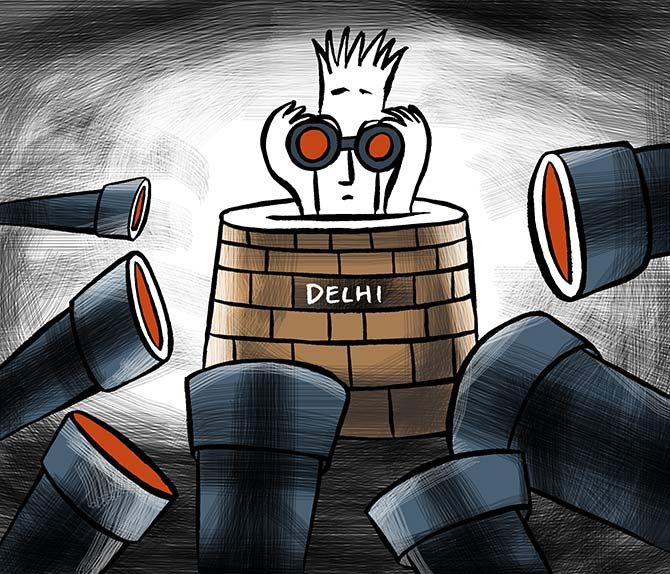

'There's nothing in the 2019 campaign air, the chunavi hawa that tells you it's a wave election, for anyone,' argues Shekhar Gupta.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

You have to get out of Delhi often if you want to understand that there are two ways of looking at India: Inside-out, that is, from Delhi and the heartland at the rest of the country; or outside-in, which is, looking at the heartland from beyond.

Essentially, when you look inside-out, it brainwashes you into seeing the picture purely in national party-national leader terms.

If you give yourselves the gift of distance and an open mind, you might see the change in this new India.

National parties as we knew them are in decline.

The concept of the Great Pan-National Leader ended with Indira Gandhi.

What about Narendra Damodardas Modi? We will come to that in a bit.

This new writing on the great political wall of India was read out to us by two of our strongest state satraps, not even regional leaders.

Telangana strongman K Chandrashekar Rao and young Y S Jaganmohan Reddy in next-door Andhra made the same point, each in his own chosen words: There is no such thing as a truly national party in India any more.

The ones you describe as national parties, the BJP and Congress, are also regional.

They just happen to have a footprint across a few states.

The Congress declining as a national party you can understand.

But how can the BJP not be called a national party? After all, it won a national majority of its own in 2014.

Get out of Delhi and see.

Sitting in Delhi, we confuse the Hindi heartland for the nation.

The BJP's 2014 majority tally of 282, for example, mostly came from UP, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Haryana, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand (190).

Of the rest, 49 came from the two western states, Maharashtra and Gujarat.

This accounts for 239 seats of the 299 in these states, a strike rate of 80 per cent.

From the rest of the country, which is the entire south (Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu), east (north eastern states, West Bengal, Odisha) and even including far north, Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab, the party only won 43 out of the 244, or just 17 per cent.

Plot this on the map of India.

This isn't the footprint of a pan-national party.

It is a 10-state party, which maxes out the seats there and gets a majority.

And pan-national leaders? Mr Modi is the only one today with that claim.

Everybody knows him. But can he get people to overwhelmingly vote for him in more than these 10 states?

Even within these 10 states, in the most important ones, his challenge comes from local parties and leaders.

He is now fighting a make-or-break battle in Uttar Pradesh with Mayawati and Akhilesh Yadav.

Bihar's equivalent of these state leaders is Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar.

Both the Congress and BJP have aligned with one, as a junior partner.

In Punjab, the BJP is an adjunct of the Akali Dal, in Haryana, both the BJP and Congress are searching for a local ally.

Even Mr Modi, with his phenomenal oratory, cannot swing a majority for his party, even hypothetically, by himself in more than seven states today.

Hypothetically, because these include Uttar Pradesh.

Check out the Congress.

If the BJP is a national party of seven-nine states, Congress has just six, albeit many of these smaller: Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, Punjab and Karnataka.

It is extinct in West Bengal, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, UP and Bihar.

That's why the maximum the Congress can aim for, if all the electoral Gods smile on it, is about 150.

I know it's unlikely and 100 will be an optimistic target.

But it serves our limited purpose of proving that if the BJP is half a national party, the Congress is no longer even a one-third.

You want a further reality check? Name a state, any one state, where Rahul Gandhi could swing this Lok Sabha election by himself.

The fact is, Indira Gandhi was the last truly national leader who could win in almost all states.

Since her passing, barring the unusual election of December 1984, no truly pan-national leader or party has emerged.

That space has been taken by charismatic, powerful leaders of states and castes.

To call any of them even a regional leader is a misnomer.

Vote tallies support this hypothesis.

From just about 4 per cent in 1952-1977 now regional/state parties's vote share has risen to 34 per cent (2002-2018).

This summer it will go higher.

What's even more important, because these parties' vogue is concentrated in a region, they get more bang for the buck, or seats for their vote percentage.

Today, with 34 per cent vote, these parties win 34 per cent of the Lok Sabha seats.

With each additional per cent, they get 11 more seats whereas the national parties get just seven.

I am taking this data from The Verdict by Prannoy Roy and Dorab Sopariwala -- just in case you thought I made it up.

In undivided Andhra Pradesh, the Congress vote share was traditionally around 40 per cent.

It has fallen to just under three in the new state.

The BJP's boasts of a coming boom in West Bengal and Odisha will be tested soon.

But, barring Assam and Tripura, it has conquered no new frontiers, despite a Modi with a majority and Amit Anilchandra Shah with his BJP membership of 100 million.

India, today, has about 20 leaders so strong within a limited geography or political demography that no national leader, including Mr Modi, can take their voters away.

Most of them have acquired administrative and political experience, and networked across regions.

They might have different concerns and ideologies, but are united on one point: Abomination of dominant national parties.

There is a large, populous and progressing world outside of our Hindi-Dilli dugout that doesn't share the insecurity of our elites in the polling season, of a 'khichdi' taking over if Mr Modi doesn't win.

You can spend days in the south and the east without hearing that familiar chatter: But if not Mr Modi, who?

For three decades now, as the Congress declined, India has been evolving into a truly federal republic, and the idea of a national election has been replaced by a sum of 30 state elections -- as it should be, with no party dominating even a third of the states, and the BJP plus Congress significant in less than a half.

Why does the TINA (There is No Alternative) factor dominate the politics of the heartland, but doesn't impress people beyond these?

One important factor is that in none of the states where the Congress and BJP fight for domination a true regional leader has grown.

In Bihar and UP, Lalu, Nitish, Mayawati and Akhilesh are formidable leaders, but each has his or her limitations.

The BJP either challenges them or compels them to share the turf with it.

Of the major states, national parties still dominate Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, and, to some extent, Karnataka, since they lack their own leaders.

The second reason is, of course, national parties do not like to build strong state leaders.

The Congress committed suicide in Andhra Pradesh rather than let the obvious successor for its state satrap grow.

It was so furious with his ambition that it didn't even treat him with basic respect after his father's death in a helicopter crash.

It has only one state leader of consequence, Captain Amarinder Singh.

The BJP today has just none, maybe a half, Yogi Adityanath.

The three others -- Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Vasundhara Raje and Raman Singh -- have been consigned to deep-freeze.

Indian politics, therefore, is at an interesting juncture with no truly pan-national leader or party and yet a declining insecurity over coalitions beyond the heartland.

As 2014 demonstrated, you can still produce a counter-intuitive full-majority government if one party can sweep contiguous states containing upwards of 200 seats.

There's nothing in the 2019 campaign air, the chunavi hawa that tells you it's a wave election, for anyone.

We can say now with confidence that this election will be fought state-by-state, more like 2004 than 2014.

Don't ask me who will lead the next coalition, because I do not know.

All I can tell you is, irrespective of who leads the next government, it will be a Cabinet in which Ram Vilas Paswan can also open his mouth.

By special arrangement with The Print