Nothing spawns the creation and perpetration of conspiracy theories more effectively than an official obsession with secrecy, says Devangshu Datta

In India, the combination of archaic laws and an institutional reluctance to share information has meant the creation of innumerable secrets, stored in sundry files. Declassification has to be specifically requested and requests are usually refused.

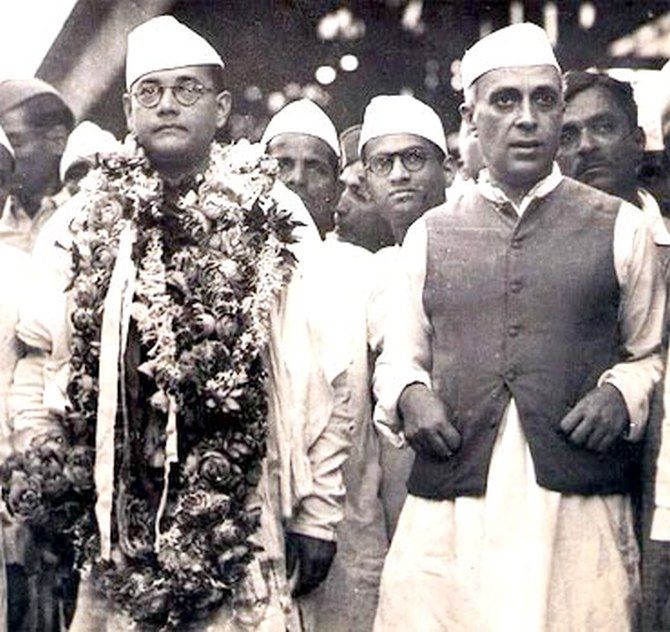

The most famous declassification requests revolve around a few incidents and individuals. There is the tamasha centred on Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. There is the Naval Mutiny of 1946.

The death of Shyama Prasad Mukherjee in Srinagar in 1953. The death of Lal Bahadur Shastri at Tashkent in 1965. The Henderson-Brooks Report, analysing the 1962 India-China military debacle.

In each case, declassifying pertinent files may lay some ludicrous theories to rest and perhaps exonerate unjustly vilified persons. The multiple theories about Bose, for example, cannot all be true. Perhaps he died in that plane crash. Perhaps he died in a Soviet gulag. Perhaps he became a sadhu.

We know that everyone concerned is dead. Officially, the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government refused to declassify related files about Bose, the Indian National Army and the Naval Mutiny, because the information would be detrimental to India's diplomatic relationships.

That is plain absurd: no nation will reboot its 21st century diplomatic relationships on the basis of events in 1945-46. Equally, there was no reason for the Narendra Modi administration to set up a committee to review the Netaji material.

Just release the files!

Bose made political errors. We know that. He allied with Japan, which had a bad war-crime record and ran oppressive regimes in occupied territories. The Indian National Army was raised by coercing prisoners of war. If information in those files throws light on what Bose did and why, the nation can live with it.

There are similar conspiracy theories about Shastri's death, hours after signing a peace treaty with Pakistan. Again, successive governments have refused to declassify the Tashkent-related documents. Ayub Khan of Pakistan and Leonid Brezhnev, who brokered the deal, are also dead.

The Soviet Union itself is dead. India doesn't have a great relationship with Pakistan. But it is unlikely to be affected, one way or the other. The release of the Henderson-Brooks report, too, may not reflect well on individuals from that time. Yet once again, they are all dead.

Apart from well-known incidents such as these, an obsession with secrecy about the daily business of governance is actually more insidiously damaging. The Right to Information Act barely makes a dent in this secrecy because information can be held back arbitrarily.

At a purely utilitarian level, the hoarding of information and the consequent lack of analysis guarantees inefficiency.

Every government and every arm of government makes mistakes. Smart governments try to prevent the same mistakes being made twice. For that matter, when difficult situations are tackled effectively, smart governments internalise and institutionalise the lessons.

In India, this doesn't happen due to the lack of institutional systems for automatic declassification and mandatory information releases. Successive administrations just repeat the same errors multiple times.

Look at inter-state disputes, disaster-relief, communal tensions, counter-insurgency, geopolitics. At the Centre and in various states, the same disastrous errors have been merrily repeated time and again.

Most advanced nations declassify and publicly archive confidential material by default, after a given time. Every nation has ‘escape clauses’. Documents can be held back from default release. But a specific senior bureaucrat, or politician, must give reasons for exclusion from release.

Britain had a 30-year rule. That was pared down to a 20-year rule recently and the process has been accelerated. he United States has a 10-year declassification rule. America also has an automatic 25-year review of any documents held back at 10 years. This is, in effect, a secondary 25-year rule.

India needs some legislation of that nature. An information-rich society is, invariably, a more prosperous society. We cannot pretend to aspire towards modernity and prosperity, while perpetrating a nouvelle caste system where information is hoarded by a small elite.