'We asked Shashank Arora to go at nine in the morning and shit on the beach. We wanted him to sense what it feels like to have no personal space.'

'We wanted my father not knowing what he was doing, because it reflects on the kind of character he is in the film. Not giving him the script added to the situation the actor is in.'

'We would not say good or anything encouraging to Ranvir Shorey after each shot. We would not even talk to him.'

'We were always trying to get people out of their comfort zone. I think that's when the acting stops and something organic starts to come out.'

Kanu Behl -- who has directed one of the most awaited films of the year, the most unusual movie Yash Raj Films has ever produced -- discusses Titli with Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com

Kanu Behl makes his directorial debut with the intense violent, and ironically named film Titli (Butterfly), a film inspired by his difficult relationship with his father and the dynamics within his family.

Behl, who had assisted director Dibakar Banerjee (LSD: Love, Sex Aur Dhokha and Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!), has taken his film to various festivals in the world, where the film has received rave reviews.

Behl tells Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com more about the film.

After watching a film like Titli, I think you come across as a very calm person. Where does all this violence that you portray in your characters come from? Have you witnessed violence like this?

Not as extreme as there is in the film.

You have to realise once you dive into a world of fictional film you are anyway enhancing for effect.

A lot of the physical violence actually happens in the early part of the film. It sets you up.

It's almost like nudity in some films where it is not exploitive and you see that they get it over with soon enough. Then you can move on to what is really the core of the film.

For me, the film is not about the physical violence. It's about the psychological, mental role playing violence that happens within families. So we wanted to finish the physical violence in the beginning. Let people settle down after seeing that.

Once you have seen violence committed by a particular character then each time he appears on the screen, you are sitting on edge.

Right. Everything is clouded by what you see. It's harrowing because you have seen it and now you know what these people are capable of doing. And now you are going into the domestic lives of these people.

What is interesting is that you do not present cardboard characters. You show their vulnerability.

The idea was to delve into these characters and where do they come from, rather than looking up at them as if they are god-like and judging them.

We wanted to look into their heads, including that of the father character, and see what are they made of.

In India, we make so much of the family. It is almost like the holy cow. Whereas in real life, you just go through situations which are very similar.

When we were writing we were saying why doesn't anyone talk about it? When we talk about the family dynamics, why just take one point of view?

Sure, we come into the film thinking it is the story of Titli, but it is the story of everybody else around him as well. Because everybody, at the end of the day, is the centre of their own world and is trying to achieve the best for themselves.

Having seen these relationships over the years in my family -- it might not have been this violent, (but) I have seen the unseenness, conscious looking away from things and denying things exists.

Lot of close relationships you see in the film I either directly witnessed in my own family or from people around me.

It's just heartbreaking to see people know that it is happening and that no one is acknowledging it. We wanted to speak about the unspoken.

How easy or difficult was to portray your family's story? Have your family members, your parents, seen it?

Yes, my parents have seen it. They were at Cannes with me.

My father is in the film. He plays the father in the film as well. His name is Lalit Behl. He's a trained actor, a graduate of the National School of Drama. But it's his film debut.

He was okay with it when you cast him initially?

Well yes, it was sort of a biggish decision.

Once Atul Mongia, my assistant and casting director, and I sat down, we said we have looked at everybody else and we are not getting what we want.

This choice of casting is loaded because he will bring to the film something that he knows. He knows the rhythm of the family that we are trying to create intimately. We don't need to tell him.

Did he actually talk to you during the making of the film?

One of the decisions Atul and I made was not to give him the script during the making of the film.

He was the only actor who worked without a script. We shot the climatic scene between Titli and the father on the last day and only on that day we sat him down and told him what the film was about, what we had been doing as well as what he had to do in that scene.

We wanted my father not knowing what he was doing, because it also reflects on the kind of character he is in the film. Not giving him the script added to the situation the actor is in.

Did you think he would be uncomfortable with the story?

Not really. That probably was one of the motivations, but we developed our own system of working with actors.

But this is your father after all.

Once you come on the set, everyone is an actor. So the father-son relationship was thrown out of the equation.

We approached Ranvir Shorey (who plays Titli's eldest brother) differently and the idea was to make him very uncomfortable to the point that on the third day, he walked up and asked if he was doing anything good.

We would not say good or anything encouraging after each shot. We would not even go up and talk to him. And both of us walked away at that point also.

Ah, so the insecurity in the actor came out.

Yes. So we were always trying to get people out of their comfort zone. I think that's when the acting stops and something organic starts to come out.

With Ranvir, we left him at sea and let him swim on his own, because we knew he was capable.

What did you see in Ranvir that he could bring out all that anger from within?

I have been a huge admirer of his from the time I was a kid. It's not so much about his film work, because he has not been used enough in Indian films.

It's about his theatre work. He has an amazing range as an actor. I had no doubt that he could do this role.

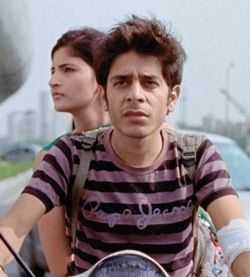

How did you find Shashank Arora?

How did you find Shashank Arora?

Shashank is a strange connection.

I knew him as a five year old because he is my best friend's little cousin. I had seen him as a kid and he used to hang out with us. They were our landlords, but then we moved to another locality in Delhi and I lost touch.

Several years later, when I was in Bombay, my friend called and asked if I remembered his cousin Sunny. He told me, 'He's grown and he wants to be an actor and he is coming to Bombay.'So my friend asked me to help him out.

I met Shashank around 2008.

Did he have any training as an actor?

He's a graduate of Whistling Woods (director Subhash Ghai's movie school).

Around the time of Titli, we were looking for our principal character, Atul asked me to give him a template of the character. I went back to that reel and said this is the closest kind of an actor we are looking for. Atul suggested why don't we test him.

When we started working with him, we realised that he is one guy who is the furthest from the part he was going to play, so the performance was a huge achievement for him. Like Neelu (Shivani Raghuvanshi who plays Titli's wife) is a non-actor, but she belongs to that world.

Shashank came from the opposite end of the spectrum.

It is not like I could tell he was acting, but it was fascinating to see the way he edges his face in front and squints, getting the facial lines. Those are thoughts you put in his mind?

Yes, that's him.

We were doing lots of wild exercises with him, not necessarily preparing him for the part.

We live in Versova (northwest Mumbai), right by the beach. We asked him to go there at nine in the morning and shit on the beach. We wanted him to sense what it feels like to have no personal space.

The idea of being in this house where it is crowded and he feels strangled. And everything else that came out, the performance is his own outlet of what he was put into.

Our idea was to get him into the mind space of this guy who has lived there all his life.

You had said you went through a couple of drafts of the script. Was that with the intent that each character had to have his breathing space?

We were also finding the script.

There is a quote by Jean-Luc Goddard that goes you don't make the film, the film makes you. That was the process. We were just stumbling around and asking the right questions. The script was writing itself.

The original idea was that I wanted to make a film about a boy being oppressed and wanting to break out. That's where it started.

Once we wrote that script, the film seemed to be working, but some of the characters were cardboard.

We knew we couldn't stop there and wanted to investigate more. We kept on writing, letting all the characters speak their voices, it emerged and it discovered it self.

By the end (screenplay writer) Sharat (Kataria) and I realised the film is about circularity and patterns running within a family and how people think that they can run away and escape it, but they don't realise that it is rooted within them.

The person they are running away from is already inside them.

What are your concerns of releasing the film in India because of the violence? Do you think parents should not bring their kids to see the film?

It is certainly not a film for young kids. But it should be shown to the youth. If it is seen correctly, it will save many people a lot of heartbreak in their lives. It is an important film for young adults and teens.

There have been a lot of violent films. Anurag Kashyap has been making and writing such films all the way from the days of Satya. But the violence you show is rare in Indian cinema.

It is not violence for the sake of violence. The physical part is carefully chosen to put the audience in a certain mood.

One thing we all were careful about was how we did not want the film to be exploitative because we were dealing with material that can end up being very exploitative.

How do you think Indians will react to this violence? You haven't made a mass scale film like Kick.

I think the psychological violence will make them uncomfortable.

It's a film that doesn't look away. But that is the film. I think it is still a very accessible film, because it is talking about people we know.

You made the film under Yash Raj Films. How did Aditya Chopra react to it? Clearly the company that he inherited from his father has a certain image and he continues that image with most of their films.

He was amazed and he really liked it. Everyone is busy and a lot of things are happening at YRF. He's been a huge supporter from the beginning.

We had gone to the shoot and then were in the edit for nine months.

When we screened the film, everybody was surprised by the sheer force of how it had transformed on the screen.

Hopefully, this is the beginning of something else they want to do.