Celebrated for his stories laced with wry humour and folk wisdom and his way of making words come vibrantly alive, Rajasthani writer Vijaydan Detha passed away recently. Rajni Bakshi salutes the literary icon's memory.

Celebrated for his stories laced with wry humour and folk wisdom and his way of making words come vibrantly alive, Rajasthani writer Vijaydan Detha passed away recently. Rajni Bakshi salutes the literary icon's memory.

Few Indians are familiar with the writings of Vijaydan Detha. When the pre-eminent Marwari writer passed away on November 10, he was mourned primarily by fellow Rajasthanis, and a perhaps, a sliver of the literarily inclined in the Hindi belt.

Yet Detha, better known as 'Bijji' was an unsung figure of world literature. Bijji's voluminous body of work will live long because it is imbued with a wealth of experience, insight and modes of expression that lie outside the English-speaking world.

This may be why he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2011.

Bijji was a born storyteller in a somewhat literal sense. His family belonged to a sub-caste known as 'Charan' who were traditional story tellers and poets -- custodians of an oral literary tradition for as long as anyone can remember.

Bijji lived both within this tradition and expanded it. He was an excellent oral story teller as well as a prolific writer of both folklore and contemporary tales.

Writing, Bijji once told a reporter, was as natural for him as 'singing is for the koel (nightingale) or dancing for the peacock.'

Writing and speaking English was another matter. While he was in school, class mates jeered at his inept pronunciation of English words -- creating in Bijji a life-long resolve never to speak or write in that language.

But that didn't stop him from reading a wide range of world literature -- be it Miguel de Cervantes or Anton Chekov or Gabriel Garcia Marquez -- in English translation.

Early in life, he chose to settle in the village of his birth, Borunda near Jodhpur, and remained anchored there physically, spiritually and culturally all his life.

Along with his friend, Komal Kothari -- a folklorist and ethnomusicologist -- Bijji founded Rupayan Sansthan, established for collecting folk tales and songs to bring out the richness of the Rajasthani language at Borunda in 1960.

'My village was my university. My literary education, if there was any, came from rural women who always had so many interesting stories, anecdotes and wisdom to share,' Bijji told a reporter from The Hindu in 2011.

'Unlike conversations of men, who were corrupted by their travels outside the village and their interactions with different people, feminine gossip was such a landmine of interesting ideas,' he had said.

"Bijji's writing retained the colourful bouncy quality of oral story telling," says Mukund Lath, a senior fellow of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

"When you consider the vast volume of folklore that Bijji committed to writing," says Lath, "you have to marvel at the depth of knowledge, creativity and learned self-awareness among the village communities that Bijji knew so well."

At Sandhan, a Jaipur based non-governmental organisation working on education, some 600 short stories by Bijji have been translated from Marwari to Hindi and used both for teacher training and workshops with children.

At Sandhan, a Jaipur based non-governmental organisation working on education, some 600 short stories by Bijji have been translated from Marwari to Hindi and used both for teacher training and workshops with children.

"These stories help us train people to reflect on and question relations -- particularly on caste and gender," says Sharda Jain, director, Sandhan.

'There is a Hitler in every one of us. It draws its strength from condescension for another being and the realisation of the power to overpower and destroy it,' Bijji once told a reporter while describing what may well be his most famous story -- Alekhun Hitler (Untold Hitlers)

This is a story about five men riding on a tractor who are outraged that a cyclist has overtaken them. They give chase and finally crush the cyclist. Only overtly the tale of a chase, the story was inspired by a heated moral discussion among villagers that Bijji once overheard while riding the bus between Jodhpur and Borunda.

Bijji's stories were marked by a sensitive depiction of power relations and gross injustices but laced with wry humor, adds Jain who was also a friend of the author. Though he tackled many stark issues, his characters were never black and white.

By narrating traditional folklore in a modern lingo, Bijji transformed the folklore itself -- turning it into major literature with its universal themes, says Arun Kumar, a one-time journalist and Delhi-based social activist.

"Bijji's stories were narratives about the complex value structures and social systems of what Bharat (pre-modern India) understood in its own terms and with its own categories of thought," says Kumar.

Aruna Roy, the well known Right to Information activist, said about Bijji, "He was one of the most progressive voices of our times."

Though Bijji had no overt political convictions, says Roy, he encompassed the best of tradition -- particularly that part of tradition which was a commentary on social inequalities and injustices.

Bijji's stories were earthy, born of the soil, and layered with irony. On the gender issue, adds Roy, he broke all boundaries with a story about a girl who pretends to be a man and marries a woman. The story was told with a poetical mysticism that was more evocative than descriptive, recalls Roy.

Decorated with a Padma Shri in 2007, Bijji also won the Sahitya Akademi Award for Batan ri Phulwaari (Garden of Tales), a 14-volume collection of stories drawing on the folklore of Rajasthan.

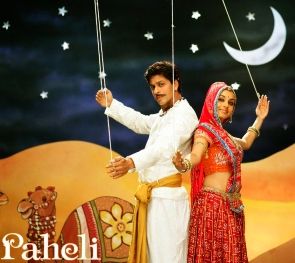

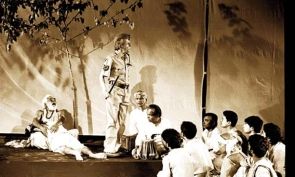

Some of his stories were adapted for plays and movies including Habib Tanvir's play Charandas Chor, left, Prakash Jha's film Parineti, Amol Palekar's film Paheli, left, above, and Mani Kaul's film  Duvidha.

Duvidha.

Over the last two decades some of his works were translated into English by Christi A Merrill, who teaches in the Department of Comparative Literature and the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Michigan.

Merrill, an American, has said she was drawn to Bijji's works partly out of a 'dissatisfaction with the pervasive sense of American superiority' and 'the logic of colonialism'.

'The more I worked with him, the more I suspected he relied so much on local oral sources in part because he enjoyed how much these stories defied the stereotype of "colourful backward". He was greatly inspired by the culture he had grown up with, deeply proud of it, and also committed to protecting and nurturing it,' Merrill has written.

One of the reasons that so few of Bijji's stories were translated into English or Hindi is that he was very particular about the quality and nuances of the translation.

It is possible that his work will posthumously attract more translators. It doesn't matter whether or not it will gain a popular global readership. It will always draw those who are puzzled by or just drawn to the complexities of that vast cultural and spiritual space where Bharat, that which is pre-modern, meets 21st century India's aspirations of dignity for all.

Rajni Bakshi is the Gandhi Peace Fellow at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

Buy Chouboli & Other Stories here.

.jpg)