If Patel had lived a few years more, he may or may not have become prime minister. But for sure, his presence would have kept Nehru in check, points out Harishchandra.

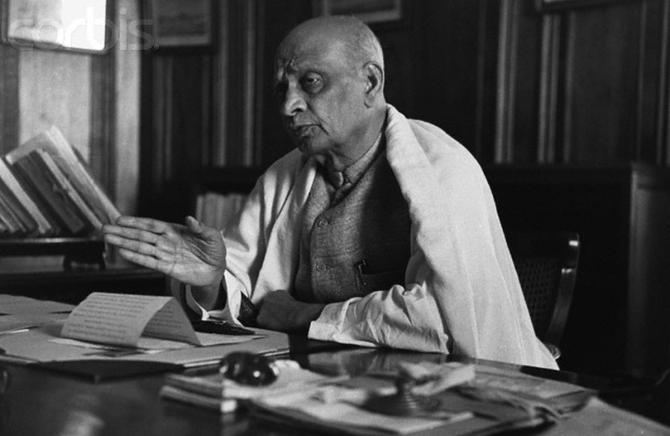

December 15 marks Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's 75th death anniversary.

He was 75 years old when he passed away in 1950, and after the passing of Mahatma Gandhi nearly three years earlier, the second-most important leader of a newly Independent India.

There is an entire school of thought about what if Patel, and not Jawaharlal Nehru, had become India's first prime minister.

But another key question to be asked is, what if Patel had lived a few years more?

It is in some ways an even more tantalising question with immense possibilities.

Perhaps the greatest gift that Patel would have bestowed upon India if he had indeed lived longer might have been a more viable and less radical right-of-centre Opposition party.

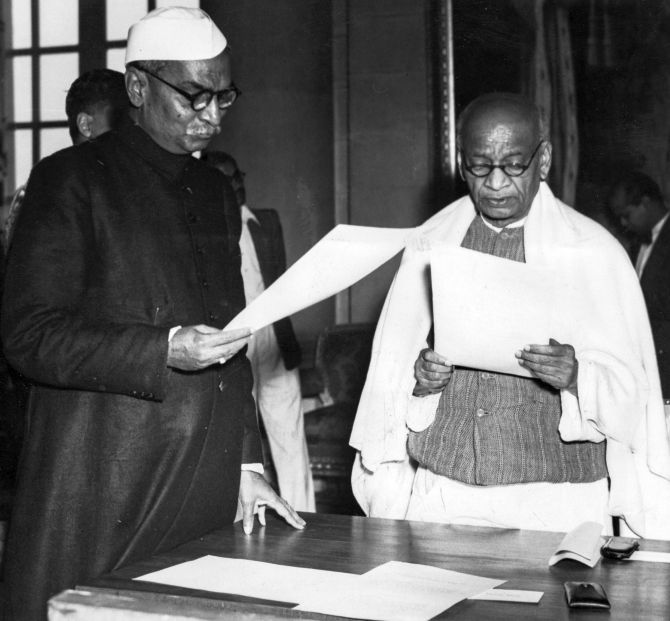

Patel and Nehru had many differences, and these were buried in the immediate aftermath of Mahatma Gandhi's assassination on January 30, 1948, when both chose to put aside their differences and work together.

They did that admirably: Housing the millions of refugees who had entered India, ensuring the integration of the numerous princely states with India, stopping Pakistani aggression in Kashmir, and, above all, creating such a robust system of governance that after all these years, democracy in India continues to thrive.

But by 1950, their differing world views meant that they were clearly drifting apart.

It is quite possible that before the 1952 election, Patel might have broken away, taking a sizable number of Congress supporters with him and contested Independent India's first election as the leader of a distinct party.

It is also possible that he might have stayed on in the Congress, choosing to exert influence over Nehru and the Congress, strengthening governance, and guiding policy for the benefit of the nation.

For instance, one of Patel's last letters to Nehru, dated November 7, 1950, warned him about the perfidious intentions of China that had just a month earlier annexed Tibet.

Like Nehru, Patel was intelligent and realistic enough to know that India, in 1950, did not have the wherewithal to take on China by sending troops to help the Tibetans.

But, unlike Nehru, he would not have ignored the Tibetan issue and gone on to befriend China, which peaked in Hindi-Chini bhai bhai (India China are brothers) only to come crashing down in the early 1960s with India's defeat by China.

It is a humiliation that still rankles Indians, and which forever tarnished Nehru's legacy.

On the economic front, many believe that Patel would have pushed for a larger role for the private sector in the economy, but that is questionable.

It is worth noting that in the 1950s, socialism was the zeitgeist of the world.

Patel would most probably have pushed for the nationalisation of key industries and a key role for the public sector.

After all, in the 1950s, most Indians did not trust traders, whether foreign or Indian.

But hailing from a state of traders, chances are that Patel would have given the private sector a bigger role, and certainly after it became evident that the public sector was simply not delivering as expected.

Would Patel have pushed the Pakistanis out of what is now Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK)?

Many people in this day and age like to think so, but there is little reason to believe so.

As everyone loves to point out, Patel was a realist, and he would have settled the issue in a non-emotional manner.

Just as Hindu-majority Hyderabad and Junagadh were integrated with India, regardless of what their erstwhile rulers wanted, he might have conceded Kashmir to Pakistan.

But would he have given up Kashmir after the Pakistani invasion?

Perhaps not, if only to keep Pakistani ambitions in check.

After all, a Pakistani victory in Kashmir might have led to further reckless adventurism.

Patel had sufficient experience in dealing with overambitious princes to know when and where to draw a line.

What if Patel had split from Nehru and formed his own party?

Back then, many Congress leaders who were politically right of centre found it difficult to work with Nehru.

Congress stalwart C R Rajagopalachari even founded the Swatantra Party in 1959, but by then he lacked the national stature to stand against Nehru.

But if Patel had been alive, chances are that a right-of-centre party may well have formed earlier, with a different political and economic philosophy.

Patel clearly had the stature to stand against Nehru, and would have had the support of many leaders and millions of Indians, though probably not enough to dethrone Nehru as prime minister.

Yet, if he had formed a strong right-wing party, perhaps the greatest benefit would have been that such a party, led by Patel, would have been able to win massive support without having to resort to communal violence and the targeting of minorities.

Patel was committed to secularism and had little use for those who used religion for political gains.

After all, he quickly banned the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh after Mahatma Gandhi's assassination, lifting the ban only after the RSS promised to respect the Constitution and flag.

If Patel had lived a few years more, he may or may not have become prime minister. But for sure, his presence would have kept Nehru in check.

Paradoxically, that would have actually helped cement Nehru's legacy. And it would have no doubt benefitted India!

If only...

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff