...a time when his legacy ledger was still positive and before the debacle against China.

With every subsequent election, our leaders tend to become weaker.

India should consider passing a law that no person should hold the highest office in our country for more than two terms, points out Harishchandra.

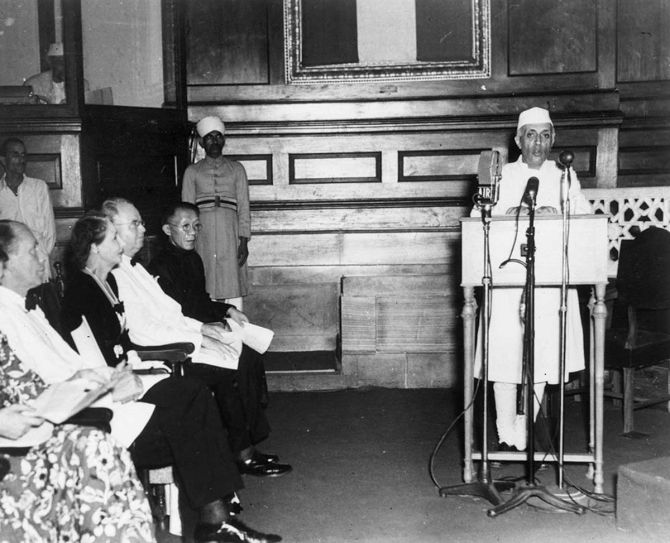

Jawaharlal Nehru is spoken about more today than at any other time after his demise on May 27, 1964.

The quip 'It is Nehru's fault...' has become akin to a default setting for the present government and its many supporters.

Nehru was India's longest serving prime minister -- he held the post for 16 years, 9 months, and 11 days, a record that Narendra Modi can overtake on March 10, 2031, when he will be 80 years old.

The problem with long tenures is that it gives you more time to make mistakes.

British Conservative politician, Enoch Powell, well known for his 'rivers of blood' speech when he opposed the immigration of Indians into the UK in the 1960s, had also, less famously, said, 'All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs.'

Nehru was not cut off mid-stream, unlike many of his peers, and is therefore, rightly and wrongly, blamed for much of India's present ills.

The greatest inconsideration made by the politicians and their supporters who love to decry Nehru is in failing to consider the context of his times.

It is extremely easy today to look back and wish that Nehru had done things differently, yet in the age when he lived and made his choices, it would have been the choice of most others in the same or similar situation.

Let's look at a few of the charges against Nehru. A popular claim is that Mahatma Gandhi erred in choosing Nehru over Vallabhbhai Patel to lead India as the first prime minister.

Yet, any such claim is unfair to Gandhi, Nehru, and Patel.

The choice of Nehru closely reflected the support of Indians. Nehru was immensely popular with the people, just like Modi is popular with millions today.

Nehru's advantages were clear: He came from North India (he was a Kashmiri Pandit whose family was settled in what is now Uttar Pradesh, the subnational region with the largest population); he came from an aristocratic background, which impresses most Indians; and he was a brahmin (something that mattered much more than it does today).

By contrast, Patel hailed from Gujarat, the same state as Gandhi and any leader would be hesitant to push a leader from his region to avoid claims of parochialism.

Patel also came from a relatively modest background, and he was a Patidar.

The last bit is interesting: The Patidars (often having the surname Patel) is today one of India's most wealthy and influential communities, and politically powerful in Gujarat, which was formed in 1960, but in the 1930 and 1940s, the Patidars were still a rising community.

A look at the galaxy of leaders involved in the Freedom Struggle and many so-called upper caste names pop-up; few OBC leaders' names come up, and if they do, it is mostly at the regional level.

For many Indians, who still see leaders from the lens of caste and region, a north Indian brahmin would have always been preferred, especially to those living in north India.

There was also the factor of age: Nehru was 14 years younger, and seen as being able to guide India in the immediate period post-Independence.

In 1947, Nehru was in his late 50s whereas Patel was in his 70s and already suffered a heart attack.

A good leader chooses what is the best for the country and if Gandhi actually made that choice, he chose what was best for India.

A second criticism concerns Nehru's economic policies, with his preference for State-owned enterprises.

By far, this complaint is profoundly unfair. Today, even Modi talks of an Atmanirbhar Bharat and urges citizens to buy local stuff -- if this isn't Nehruvian, then what is?

Indians in the 1950s were acutely conscious of the fact that the British came as traders and stayed on as rulers to plunder.

There was no way Indians back then would have accepted foreign investment or even the presence of big foreign companies.

Swadeshi was not just a political slogan; it was an economic dream that Indians harboured along with a mistrust of all foreigners.

Further, Indians have a love-hate relation with traders (and the trading community) of India.

In the 1940s/1950s, we loved to hate the traders -- Hindi movies of yore invariably showed the shopkeeper/moneylender as a slimy, untrustworthy person, forever seeking to lay his hands on other people's money.

Indians were happy to see the government ringfence big business. Moreover, in the mid-1940s, Indian industrialists had themselves propounded the Bombay Plan, urging the government to invest in heavy business, acknowledging that they lacked the ability to make large investments.

Across the world, the zeitgeist of the 1950s was State-owned large industries (steel, coal) and India was no different.

Every leader is a product of his time, and state ownership of India's best assets was something heartily approved of by Indians.

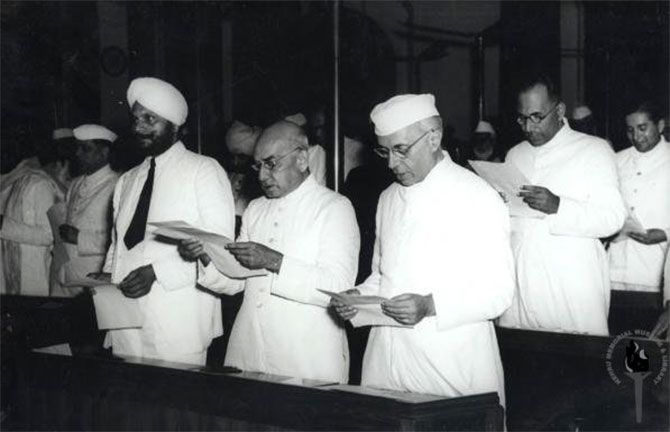

What India owes Nehru is democracy and secularism (the latter is quite hated today).

At a time when the first elected leaders of newly independent countries were happy to dispense with the pain of elections, Nehru chose to do so otherwise.

Democracy wasn't a given: We have seen across Asia and Africa how easily it has been destroyed.

If today, Indians can take pride in India still having a functioning democracy, some credit for that belongs to Nehru.

He also deserves credit for keeping India secular, though here he was carrying forward the legacy of the Freedom Struggle, that was genuinely secular in character, even after the rise of the Muslim League, which wasted no opportunity to needle the Congress party.

All the leaders back then -- Nehru, Patel, Rabindranath Tagore, Subhas Chandra Bose, et al -- were firm believers that India needed to be secular, with the government not interfering in the religious lives of people.

Secularism, or the separation of the temple from the temporal, wasn't just a political decision but stemmed from the very root of Indian civilisation.

In India, the clergy and the rulers have always been separate (think brahmin and kshatriya): A principle propounded and practiced a thousand years before Christ's famous aphorism to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's and unto God the things that are God's! Secularism is rooted in Indian tradition.

Where Nehru seriously erred was in his foreign policy relations, including his dealing with China, and about which, much has been written.

Nehru may have had good intentions, but history judges outcomes, and none of them were really good.

One of the gravest mistakes Nehru made was in not retiring after completing 10 years in office in 1957, a time when his legacy ledger was still positive and before the debacle against China.

With every subsequent election, our leaders tend to become weaker.

India should consider passing a law that no person should hold the highest office in our country for more than two terms.

After all, if you can't make a difference in 10 years, there is little chance you will make any difference in 15.

His other tragic error was in pushing his daughter to succeed him (though if Lal Bahadur Shastri had lived longer, it is anyone's guess if Indira Gandhi would have ever become prime minister), and she in turn, was succeeded by her son, Rajiv Gandhi.

Problem with family is the mistake of one is seen as the mistake of all and usually pinned on the person who is the easiest to blame (in this case, Nehru).

As historian Ramachandra Guha noted, children pay for the sins of their ancestors, Nehru is paying for the sins of his descendants.

Truth be told, Nehru deserves better.

Chances are, after the current wave of loathing passes, he will be judged more fairly.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff