'How many people have been skilled up and thus able to escape from needing to be in NREGA?'

'The true success of NREGA would lie in its irrelevance -- that is, people no longer need it as a crutch.'

'NREGA should enable them to climb out of poverty and stand on their own feet.'

'But this is expressly forbidden by NREGA rules. Skill development, which is what India needs more than anything else, is outside the purview of NREGA,' points out Rajeev Srinivasan.

There is a last-ditch effort to force India to save one of the most ridiculous legacies of the United Progressive Alliance government, its National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. It makes no sense because it doesn't do skill development, routinely transfers public funds into private hands, and creates hard-to-break dependencies.

But most of all, I liked the letter-writing campaign in its support.

I was amused to hear that 28 'eminent economists' had written a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi telling him, in effect, that the heavens would fall if NREGA were to be touched.

I was reminded of two similar letters: One from 47 'scholars' (the 'Witzel letter') supporting an obscure pedagogue in a California lawsuit, and another from 40 'Nobel Prize winners' in support of Dr Binayak Sen, who was accused of aiding and abetting Naxalites.

The trouble with all these letters is a logical fallacy of 'appeal to authority.' It is as though by waving these people's credentials about, the proponents can cow down and browbeat into submission even the legitimate concerns of any opponent. But, in fact, the named people may a. not be authorities at all; b. may not be authorities in the subject matter under discussion; c. may have no idea about the proposition and simply signed off under pressure from a zealous proponent.

In exactly the same vein, the brave 28 economists are attempting an 'appeal to authority,' based not on their knowledge of development economics on the ground in India, but merely on their degrees, academic positions, or some such. I have not done a background check on them, but I suspect most of them are from the Jawaharlal Nehru University stable of extreme-Left economic thinking, and therefore their neutrality is suspect. These are people who gained from the status quo ante, and they would like to preserve it.

I also wonder if they see themselves like the brave 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, or the boy-with-his-finger-in-the-dyke of Dutch mythology, or King Canute, who ordered the waves to recede. In any case, these people are attempting to stop what they consider an implacable foe, right-wing economic policies.

Is there any merit to the position that NREGA is doing a very valuable service to the nation?

Did NREGA in fact accomplish what it set out to do? And what exactly DID it set out to do?

I had the frightening experience of listening to a lecture a year ago by Mihir Shah, a member of the erstwhile Planning Commission, who apparently was the 'father' of NREGA. (I note in passing this was the second-most scary lecture I have ever been to, the scariest being one by former IAS officer Harsh Mander, he of the purple prose and vivid imagination.)

In the Mihir Shah lecture (he was predictably a JNU/Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum product), the main point he stressed was how much money had been spent on NREGA. He said, and I counted him saying it three times, 'There is unlimited funds for NREGA.'

From this I gathered that the intent of NREGA was to spend large amounts of taxpayer money. In that, it definitely succeeded. Absolutely staggering amounts of money have been spent: If I remember correctly, over 2.3 trillion rupees, which is of the order of magnitude of $40 billion over several years (or 0.35% of GDP per year).

That is the amount of money spent by the taxpayer. Most of that would have been siphoned off by intermediaries, although the economists' letter asserts that 'Corruption has steadily declined over time,' without any evidence. Rajiv Gandhi famously said that only 15 per cent of any government spending actually reached the intended recipient; that was many years ago, and given the ingenuity of bureaucrats and politicians, it is likely that only 10 per cent now reaches the recipient. That is, NREGA has been a windfall of $36 billion to middlemen.

This is a very large transfer of taxpayer monies to private hands. Of course, the UPA government was a past master at this, and it is the same thing it deployed in another absurd policy, Right to Education, which in effect transfers public money to the management of schools.

One of the big problems with entitlement spending is that it distorts incentive structures. Whatever monies reaches the recipients creates in them the expectation that the mai-baap sarkar will hereafter look after them: It becomes a right, that these funds will forever flow to them with no effort on their part.

If the government attempts to cut down on social welfare programs, or to induce people to put in some work in return for the dole, there will be social unrest, and it will be political suicide. Thus these cargo-cult activities will be in effect in perpetuity, beggaring the treasury.

The pernicious effects of give-away programmes have long been documented in the US and Europe, where 'welfare queens' have been targeted for condemnation. It is a fact that periodically, in times of great stress, it is necessary to create make-work schemes so that the poor will have a cash income to purchase scarce goods. This has been done periodically by Indian kings when famine occurred (which, thanks to El Nino, is about every 12 years or so when the monsoon fails). But to make that dole a pillar of the government's policies does not make sense.

So if Mihir Shah and other worthies saw NREGA as a programme to create a crushing burden on the State, they have succeeded. I asked him what the benefit had been for all the funds spent on NREGA. His answer was illuminating: That so many women and scheduled castes and scheduled tribes had been employed by NREGA. The same argument is put forward by ministry officials (external link) here.

I consider that to be a red herring. The real question is: How many people have been skilled up and thus able to escape from needing to be in NREGA? The true success of a programme like NREGA would lie in its own irrelevance, that is, people no longer need it as a crutch. NREGA should enable them to climb out of poverty and stand on their own feet.

But this is expressly forbidden by NREGA rules. Skill development, which is what India needs more than anything else if it is to become a global contender in manufacturing, appears to be outside the purview of NREGA, which is expressly meant for unskilled labourers.

While working with a committee on skill development, I found out this startling fact: You cannot use NREGA funds to train people to get off the dole! What I gather is that you need a specific exemption to be able to do so!

That means the idea behind NREGA is to create a pool of unskilled workers and keep them unskilled in perpetuity, while the usual suspects merrily create armies of phantom employees and other clever mechanisms to cash in on the loot.

I have seen this in action: In Kerala, you find that instead of the 1 or 2 people you actually need for a particular job such as clearing the underbrush along roads, usually 5 or 6 people show up, which, of course, ends up in highly inflated estimates of work done.

Besides, there is another pernicious effect, perhaps an instance of the law of unintended consequences. Migrant labour has been a major part of the success of agriculture in the past couple of decades, as poor Gangetic Plain labourers went to places like Punjab to harvest crops. This pool of labour is now absent, as they have been absorbed into make-work schemes in their home states; this probably is a big issue for farmers in Punjab, Andhra/Telangana, and other places with agricultural production.

The prognosis from this is not good, and agriculture, if it is economically not sensible, can vanish overnight. I speak from experience in Kerala. When I was a child, the state was full of productive paddy fields; now, almost all of them lie fallow, because labour costs became unaffordable.

That is exactly what farmers elsewhere will do, and I believe they are doing so already: Leaving land uncultivated because they cannot find, or cannot afford, the labor necessary. Agriculture, even in developed countries, has some element of labour -- my former home, California, depends heavily on its Mexican farm workers.

Thus, from several perspectives on utility and results (but admittedly not on its efficacy in being a black hole for money), NREGA is an absolute disaster. The brave 28 economists tilting against its natural death are like Don Quixote on his nag Rosinante charging the windmills -- blissfully unaware of reality; and they ought to be ignored.

Indeed, as Jagdish Bhagwati once said, 'India's curse has been its brilliant economists.' With these experts, those in the Planning Commission, and Raj Krishna, whose sole claim to fame was in inventing the racist term 'Hindu rate of growth,' it is hard to disagree with Bhagwati.

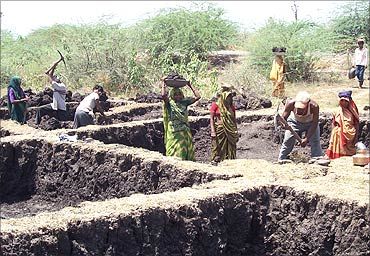

Image: Villagers working on an NREGA project.

Rajeev Srinivasan is a management consultant. His earlier columns can be found here.