Photographs: Vijay Mathur/Reuters Swarupa Dutt

As much as India's tryst with freedom, was its tryst with princely states. And we are the richer for it, says Swarupa Dutt in an Independence Day special.

An engineering graduate, fresh out of college and working for a multinational in Mumbai, was online with a senior manager in the US. It was 10 pm here and he wanted to go home, he told the American.

This is the conversation, verbatim.

Friend: Just missed the shuttle from office and I need to go home since it's difficult getting a cab from here (Powai to Thane). Could we talk tomorrow?

American: Sure. But don't wait for a cab, why don't you call for an elephant? Aren't they on hire?

Friend: Pardon, me?

American: Elephant. Why don't you call for an elephant?

To my friend's credit, he could choke down his laughter and answer the question, earnestly.

Friend: No, I'd rather take a cab because elephants are slower and it'll take forever to get home. Actually, my dad -- who by the way -- is one of the Maharajas of Mumbai, wanted to send his sedan, but I'm dead against taking help from him. We've had a situation (he used the Americanism for good measure) and I don't want the inheritance.

The American, an engineer as well, was sincere in his question, and had no idea my friend was joking. In fact, the chap confessed that he had often wondered whether my friend had any royal connections.

As surreal as the conversation may sound, it isn't really difficult to understand the rationale behind the thought.

A British woman who has been living in India for over 45 years had told me that the Americans, unlike the British, who have a shared history with us since the 1600s, do not understand the idea of India. And they don't particularly want to.

"It stems from a lack of interest in a culture that they cannot relate to and so they try to establish a connect with what they think India is --Maharajas, elephants, snake charmers and palaces. It's also, I think, a nicer vision of India, a distancing from poverty and the unwashed masses," said Mrs B, now in her early seventies.

"When I got married and came to Bombay, I did feel like a princess because of the quality of life here. We never had servants in England; here I was waited upon in a huge house enclosed by rose gardens, lawns and a kitchen garden. My great-grandfather was employed by the East India Company and for the first time, it made me feel close to a person I had never seen. It was strange, but I felt nostalgic for a period of Indian history I had only read about -- princely India."

...

Former royals still captivate India

Image: Gaj Singh of Jodhpur and Yashodara Raje of Gwalior in Berlin to mark India's 50th Republic DayPhotographs: Reuters

Then, on December 28, 1971, in an amendment to the Constitution, it was ruled that, 'The Prince, Chief or other person shall cease to be recognised as such ruler or the successor of such ruler.' And privy purses were abolished.

In effect, they had become commoners. So why is it that Indian royals still have a peculiar hold on popular culture? And why haven't they just faded away into a sepia monochrome?

The fact is, 41 years later, the erstwhile rulers still captivate India. Their 'subjects' still bow and scrape and call them hukum and Rajasaab or Ranisaheba, and when they do the rounds of swish parties in metropolitan India, they go as his/her highness.

They represent a way of life that has long disappeared and will never return because it has no sanction. It is a make-believe, a fancy dress party of turbans with emerald and diamond pins and chiffons with pearls, but it courts envy. And so royalty thrives.

Here's an excerpt from the Bombay Times, August 8, 2011.

'The Begum is wearing her joda. The three-piece ensemble is made up of a kurta, farshi paijama and dupatta made of rust and gold tissue, which contrasts subtly with the soft green satin gote at the hem. The ensemble was made for the Begum Sajida Sultan of Bhopal, who wore it for her wedding in 1939.'

The Begum here is actress Sharmila Tagore, married to the Nawab of Pataudi, Mansur Ali Khan and the reference point is Kareena Kapoor's wedding outfit. The story goes on to say that the heirloom dupatta Sharmila wore then will be incorporated into Bebo's outfit. 'As the wedding will take place at Saif's ancestral haveli in Pataudi, it will be fitting for Kareena to wear something that reflects the royal house's heritage and history.'

...

From titular heads to active politics

Image: Guests walk through the lobby of Umaid Bhawan Palace, also a Taj hotel, in JodhpurPhotographs: Vijay Mathur/Reuters

Royalty thrives because there is an unabashed voyeurism into that privileged life and a grudging respect for their legacy.

Most of the princely states had exemplary administration and civil works, and were centres of education and learning. Jaipur, Rajasthan, which showcases India to the world, has a 300-year-old town planning design, where roads had prescribed widths, and houses had regulation heights -- the entire city laid out in grid pattern.

Some of the city's premier schools and colleges were established by Gayatri Devi, married into the royal family of Jaipur. She was instrumental in getting many Rajasthani women out of purdah, home and hearth and into school.

In Kolhapur, Maharashtra, which cannot corner even a fraction of Jaipur's fame, lives the descendent of Shivaji. Showing me around his sprawling and still stunning Indo-Saracenic palace, he says he begins each day by seeking the blessings of two people: His father Chhatrapati Shahuji Maharaj and his ancestor Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Known as the Maharaj Kumar of Kolhapur, he is the 16th direct descendant of Shivaji.

His great-great grandfather, Shahu Maharaj encouraged education in his state, subsidising it for the poor and girls. He encouraged widow remarriage and stopped child marriages. He also enabled employment schemes for the poor and patronised the reformist Arya Samaj.

In Jodhpur, Rajasthan, the titular head -- Gaj Singh's father -- built the Umaid Bhavan palace, the world's largest private residence, as a work-for-food programme to provide employment to more than 3,000 artisans during a famine.

Royalty thrives because once the princely states merged with the Union, many of the titular heads stood for elections and joined active politics -- Gwalior, Jodhpur, Tripura, Kochi, Kolhapur, Jaipur, among others. All of them won the elections and someone like Gayatri Devi still holds the Guinness Record for winning an election by the highest percentage of votes polled.

...

Princely India is part of our history

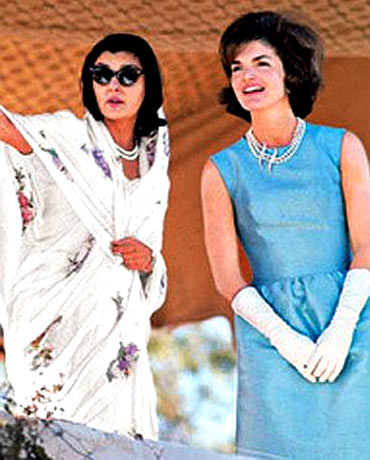

Image: Rajmata Gayatri Devi of Jaipur with then US First Lady Jacqueline KennedyPhotographs: Rediff Archives

Royalty thrives because of nostalgia. A yearning for a past that you may or may not have experienced.

My mother was born in the erstwhile state of Cooch Behar in West Bengal-- the late Maharani of Jaipur Gayatri Devi's paternal home. She remembers a childhood (pre- 1947) when Gayatri Devi and her sisters dressed in white shirts and breeches would go riding by a lake called Sagar Dighi.

Every morning, at sunrise, the Maharaja's royal band would strike up a tune to wake the royal household, loud enough to wake much of the citizenry. Cooch Behar was beautiful, my mother says.

"Compared to Calcutta during the same period, Cooch Behar was clean, it looked prosperous and I don't remember seeing a single beggar," she says.

She visited Cooch Behar a couple of years ago and wasn't surprised to see how rundown it was. The state went to seed after Partition, one of the reasons being the influx of refugees from then East Pakistan and it has never recovered.

On the flipside, most of the royal families were loyal to the British, and very few took part in the 1857 War of Independence. Smaller princely states did pillage and steal their subjects blind with backbreaking taxation. They did as they pleased, with almost no punitive action against them.

So when Independence came, princes were also pressured by popular sentiment which favoured integration with India and their plans for independence had little support from their subjects.

Princely India is part of our history as much as democracy and elections, an active judiciary, and now the Right to Information Act. It may not define who we are, but it is a part of the symbol of what the world recognises us to be.

It is more acceptable than the other Rajas -- 2G's Andimuthu or Raja Bhaiya, a Samajwadi Party MLA and the 'ruler' of Kunda district in Uttar Pradesh, who has 30 criminal offences against him including murder. It is more acceptable than dynastic politics. Or the Communist 'rulers' of West Bengal.

The idea of India is documented by its 4,500-year-old history and as much as its tryst with freedom, was its tryst with princely states. And we are the richer for it.

Meanwhile, my friend, (who did not call for an elephant to take him home), has just left for the US to pursue a PhD. In his suitcase, he showed me, is something he bought for close to Rs 3,000 -- a genuine, if slightly worn out -- snake charmer's flute. "That's for when they want to know what my father does," he grins.

Swarupa Dutt is Deputy Managing Editor, Rediff.com

Also read: India, you've come a long way

Indifference, not corruption, is India's most threatening malady

article