Islamabad and New Delhi need to learn lessons from Sarabjit Singh’s tragic saga and accord importance to evolving a prisoners’ policy. And until then there will be many more Sarabjit Singhs as the years roll by, notes Seema Mustafa.

Islamabad and New Delhi need to learn lessons from Sarabjit Singh’s tragic saga and accord importance to evolving a prisoners’ policy. And until then there will be many more Sarabjit Singhs as the years roll by, notes Seema Mustafa.

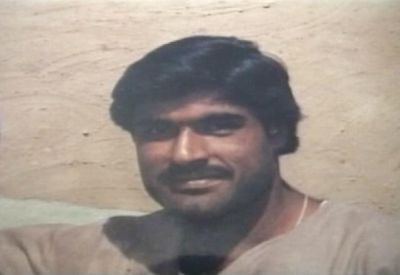

Indian prisoner Sarabjit Singh has died in a Pakistani jail. After being brutally injured by inmates, he was taken to the hospital in a semi-dead state. He has been on a ventilator, in a coma with perhaps no idea that the family he had been living to meet was by his side during his last couple of days in this world.

Singh’s is a tragic story of an operation gone wrong. Widely perceived now to be working for the Indian intelligence agencies, he had been arrested by the Pakistani authorities 13 long years ago in 1990, and charged with acts of terrorism.

Deserted by employers and state, he fought a lonely battle for justice amidst isolation, threats, attacks in Pakistan while his family ran from pillar to post seeking intervention for his return.

To cut a long story short, his worst fears came true and he was attacked brutally by fellow prisoners in the Lahore jail. And his family was finally allowed access when he was in a coma and unable to see or hear them.

Singh’s sister was on television the other day castigating both the Indian and the Pakistani government. Her pain and anger was visible as she traced the lonely journey of Singh and his family, the callousness of government, the refusal to recognise or acknowledge his presence.

Sarabjit has since died with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh breaking his silence to demand action against those who attacked him -- a little too late really as Pakistan has booked the prisoners responsible, suspended the jail staff, and ordered an enquiry into the incident.

What comes of the last remains is to be seen, but clearly it will no longer impact on Singh as he is no more.

The story has, thus, moved from Singh to the other prisoners languishing in Indian and Pakistani jails for years and years, and the need for both governments to formulate a humane prisoner policy. Civil rights groups on both sides of the border have been agitating for such a policy to ensure some levels of justice and compensation for the hundreds of Indians and Pakistanis arrested by each others’ governments, many of whom have died unsung, many others who have gone crazy, and a good majority who are living hopelessly from day to day without any hope of justice.

The worst affected in this lot are the poor fisherfolk and shepherds who stray the invisible border lines and are caught by the other side, jailed and left to rot there.

Peace activists have succeeded in securing some intervention with fisherfolk in particular released occasionally in batches, but even so the figures are reprehensible and the governments of both India and Pakistan need to act on this urgently.

It is imperative thus, for the media and other informed groups, to turn the debate of loss and suffering to that of concrete action. India and Pakistan, given their levels of distrust and non-cooperation, need a prisoners’ policy to ensure that a credible mechanism is set in place to review arrests, suggest relief and ensure that innocents who form the bulk of these ‘bilateral’ prisoners are released without delay.

Unfortunately, their future gets mired in the animosity of India-Pakistan relations where the governments actively resist measures that can improve the atmosphere, and give some relief to the affected persons.

Sarabjit Singh’s was a case in point, in that the Pakistan government could have expedited his release, but chose instead to ignore the death threats and kept him in prison without the necessary security to ensure that he remained safe.

This cannot be dismissed as just a lapse, as it is apparent that the jail authorities were acting in connivance with those who had planned the murderous attack.

And while the political leadership can claim the benefit of the doubt, the fact remains that a serious and constant review of Singh’s case by competent authorities was missing, and hence measures for his safety were not taken.

Given the fact that at the time of the attack he had already acquired the status of a high-profile prisoner, one would have expected the Pakistan government to have ensured that Singh was accorded maximum security so that an untoward incident damaging bilateral relations could have been avoided.

Islamabad and New Delhi need to learn lessons from Sarabjit Singh’s tragic saga and accord importance to an issue that both had been wishing away.

Activists recall the indifference of the governments to their campaign for the rights of prisoners, and their suggestions for setting in place a system based on international jurisprudence, compassion and security.

Singh’s story has been particularly horrific, but fisherfolk who have managed to return to India speak of similar tales. What is as bad, or even worse, than the torture and living conditions of the prisoners is the real possibility that once arrested they might never return to their homeland.

This is because of the visible indifference of both countries to their own prisoners, where the issue of their release might become a talking point in some of the official level meetings, but has certainly not become a sustained effort on either side.

And until the two sides evolve a prisoners’ policy, also including consular access and a monitoring mechanism of their physical status and safety, there will be many more Sarabjit Singhs as the years roll by.