'The most striking comment Yasser Usman makes -- not only about Sanjay Dutt, but also our contemporary society -- is about the transformation that he goes through: From being a man who claimed Muslim blood to one who is a devotee of Hindu gods,' notes Uttaran Das Gupta.

IMAGE: Sanjay Dutt seen at a party in Mumbai last month. Photograph: Pradeep Bandekar

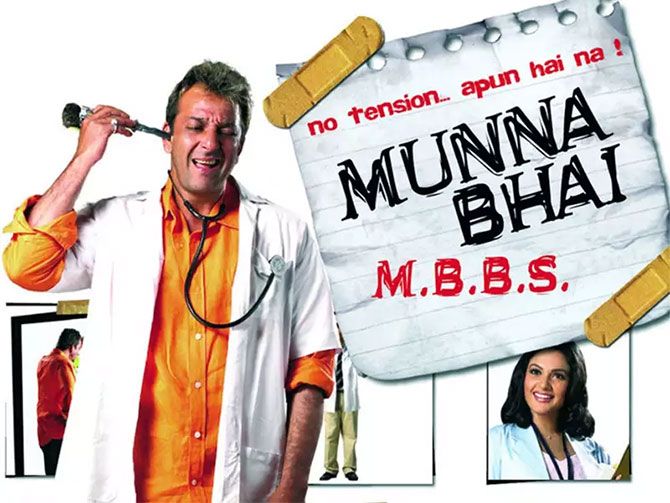

In a chapter dedicated to Munna Bhai MBBS (2004) towards the end of this book -- Sanjay Dutt's Biography: The Crazy Untold Story of Bollywood' Bad Boy, Yasser Usman writes: 'From the bratty Sanju Baba, he became the lovable Munna Bhai.'

The painful process of this metamorphosis is a fit subject for one of Sanjay Dutt's 1980s-style potboilers. (A biopic on him, Sanju, starring Ranbir Kapoor in the title role, is slated for releases later this year.)

What emerges from this narrative, however, is not merely a morality tale about a spoilt star-kid gone wrong and his reformation, but also a history of the changing landscape of Bollywood as well as political and social life in India.

Usman, also the acclaimed biographer of Rajesh Khanna and Rekha, explains his motivation for writing this book pretty early on: 'I wanted to try and explain what makes a bad boy.'

In the Introduction, he writes: 'I explored Sanjay's childhood for clues -- his boarding school days, his relationships with his mother, father and sisters, his early years in the film industry. But there are some things you just can't explain.'

He perhaps seems to give up when he says that Sanjay Dutt was a boy who refused to grow up, but the 'film-like' narrative does have a sub-plot poignant for our times.

When Sunil Dutt met his son at the Mumbai police crime branch's Crawford market office after the latter's arrest in 1993, he heard Sanjay's confession and asked: 'Why?'

Usman writes: 'Sanjay answered: "Because I have Muslim blood in my veins. I could not bear what was happening in the city".'

This was, of course, a reference to the Bombay riots, in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition.

As revealed elsewhere in the book, Sunil Dutt had received threat calls for his charity work among Muslims, and Sanjay Dutt often claimed that he had acquired machine guns from Dawood Ibrahim's brother because he expected Hindu fundamentalists to attack their Pali Hill bungalow.

This was a strange place for him to be.

His father was a Congress member of Parliament; his mother Nargis had been celebrated as the icon of Nehruvian ideals after the historic Mother India (1957).

Despite being born with the proverbial silver spoon, with entitlement that eased his way into the industry, Sanjay Dutt had fought demons since childhood -- his problems with authority, substance addiction in early youth, or a slew of bad films early in his career.

Usman's research is thorough. He has tracked down Sanjay Dutt's friends and teachers at the Lawrence School, Sanawar, and provides details of even the punishments he received for flouting the strict code of discipline at the institution.

His life had also been one of constant public scrutiny: Even his name was selected through a public contest in the November 1959 edition of the popular Urdu magazine Shama.

Usman narrates another incident to illustrate how the public lives of their parents can often infringe on the privacy of star-kids.

When Raj Kapoor's Bobby released in 1970, rumour mills worked overtime, insinuating that Dimple Kapadia was Nargis and Kapoor's lovechild. (Their professional collaboration and romance is the stuff of Bollywood legend.)

Sanjay Dutt had to bear the taunts of his schoolmates about his mother's liaisons with her co-stars and perhaps this inculcated in him a distaste for the women in his life -- wife, girlfriend, daughter -- pursuing the acting profession.

IMAGE: Sanjay Dutt on the poster of Munna Bhai MBBS.

Usman, however, makes no attempts to justify Sanjay Dutt's misogyny. He provides the star's most distasteful quotes without edits.

For instance, Sanjay Dutt justifying why he did not want his wife/girlfriend to work in films: 'I would not like to come in the evening to find out that she has gone to do a night turn... if you just want to call me a chauvinist, I'm just one.'

A strange comment indeed from the son of actors and one who has dated leading ladies -- Tina Munim, Madhuri Dixit -- of the industry.

Like the true patriarch, he also thwarted, we are told, his daughter Trishala's ambitions of working in films.

'Trishala wanted to be an actress and I wanted to break her legs,' Sanjay Dutt is quoted as saying.

Nor does Usman mince words about Sanjay Dutt's rather mediocre filmography: 'In a career spanning more than a hundred films, Sanjay has only around ten noteworthy movies, a poor average by any standard.'

IMAGE: The cover of Sanjay Dutt's Biography: The Crazy Untold Story of Bollywood's Bad Boy, which the movie star has rejected as gossip.

Usman also correctly points out that some of his best work is merely an extension of his rather colourful life, be it Khalnayak (1993), released soon after he was arrested, Vaastav (1999), where he plays a cocaine-snorting, gun-loving gangster, or the Munna Bhai films, which Sanjay Dutt's PR machinery utilised to the hilt to recast his image as the reformed bad boy.

An incident that Usman writes about is telling: 'Priya (his younger sister and former Congress MP from Mumbai) recalled Sanjay campaigning for her... his popularity was soaring... Sanjay recounted: "Apun bolta hai ki apun li behen ko vote dene ka. Bole toh? (You must vote for my sister. What do you say?".'

However, the most striking comment that Usman makes -- not only about Sanjay Dutt, but also our contemporary society -- is about the transformation that he goes through: From being a man who claimed Muslim blood to one who is a devotee of Hindu gods.

When Sanjay Dutt walked out of the Arthur Road jail on October 18, 1995, 'the taweez was gone, and tilak (was) in place.'

As Usman writes, at a time when all Congress leaders had stopped helping out Sunil Dutt, it was his political rival Bal Thackeray who helped him out.

If you are looking for a filmi twist, you couldn't have found a better one.

Postscript: After I finished writing the review, I found that Sanjay Dutt had disowned Usman's biography, calling it full of rumours and gossip.