Without changes to the taxation rules, buybacks are expected to remain scarce.

Share buybacks have all but disappeared following a rule change on October 1 last year that shifted the tax burden from companies to shareholders.

Under the revised norms, buyback proceeds are taxed as dividends at the shareholders' applicable income-tax rates, significantly increasing the liability for high-networth individuals and institutional investors in the highest tax bracket.

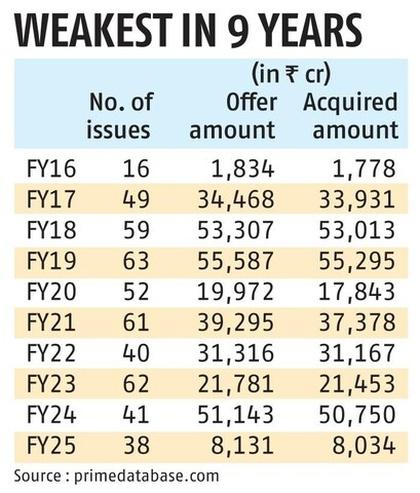

Since the change, only two buybacks have been completed: A ₹360 crore repurchase by ferro alloys manufacturer Nava and a ₹72 crore offer by online matrimonial services provider Matrimony.com.

“Buybacks have dried up since the tax-rule change, which aligned their taxation with dividends. Despite a bear market since October -- a period when buybacks typically thrive -- activity has been negligible,” said Pranav Haldea, managing director, Prime Database.

Dividends and buybacks constitute the primary mechanisms for returning excess cash to shareholders.

The new structure seeks to eliminate the tax arbitrage between the two routes.

Currently, companies incur no tax outgo on dividend payments, which are taxed solely in the hands of the recipient in accordance with their income bracket.

With the parity in tax treatment, market participants are preferring dividends as the more efficient vehicle for capital distribution.

Unlike buybacks, dividends do not require the appointment of merchant bankers, face fewer compliance requirements from the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi), and can be executed at a greater speed. Buybacks, in contrast, are administratively heavier and typically take several weeks to complete.

Between FY17 and FY19, the share of buybacks in total shareholder rewards increased significantly due to a tax differential.

From April 1, 2016, the government introduced an additional 10 per cent levy on dividends, pushing the effective dividend distribution tax (DDT) to 20.6 per cent, while listed company buybacks remained tax-exempt.

The proportion of buybacks in total shareholder rewards in FY16 stood at just 1 per cent, rising to an average of 25 per cent over the FY17-FY19 period.

To address this tax imbalance, the government imposed a 20 per cent buyback levy from April 1, 2019.

Nevertheless, buybacks remained attractive for cash-rich firms as the tax liability rested with the company, not those tendering their shares.

The most recent shift in tax incidence has, once again, altered the landscape.

A buyback entails a company repurchasing and extinguishing its own shares, thereby reducing its equity base and enhancing metrics such as earnings per share (EPS) and return on equity.

“Companies now prefer dividends to buybacks. The EPS boost from buybacks is marginal, as the buyback amount is small relative to market capitalisation,” said Deepak Jasani, former head of retail research at HDFC Securities.

The remaining strategic rationale for buybacks, he said, lay primarily in enabling promoters to consolidate their holdings by not tendering their shares.

“Only firms where promoters seek to raise their stake are likely to pursue buybacks. Otherwise, dividends involve simpler procedures and fewer compliances,” Jasani added.

Further curtailing the appeal of repurchases is Sebi's move to completely phase out the “open-market” buyback route from March 2025.

Without changes to the taxation rules, buybacks are expected to remain scarce, believe experts.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff