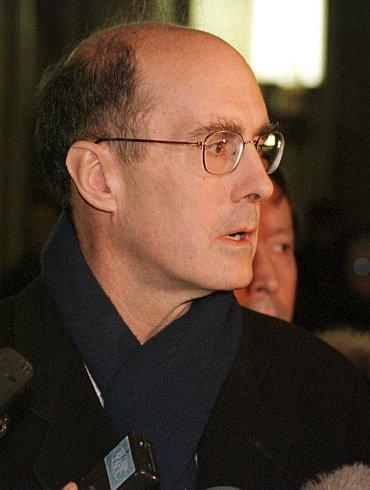

In an exclusive interview, Strobe Talbott, a key protagonist in resurrecting the United States-India relationship after India's nuclear tests in May 1998, talks about the US-India relations, Iran and the Pakistan situation to Rediff.com's Aziz Haniffa.

Talbott, the inaugural winner of India Abroad's (the leading Indian American newspaper headquartered in New York and owned by rediff.com) Friend of India Award last month in a glittering ceremony in New York, says, "India and the US are not now, and may never be allies."

Talbott, who is now president of the Brookings Institution -- a leading Washington, DC, think tank, -- adds, "And, by the way, one reason we may never be or not, in the foreseeable future, is because there is still a huge constituency in support of India's non-aligned status, despite the fact that I would say that non-alignment and the non-aligned movement is very much an artifact of the Cold War."

There is no denying Talbott's indispensable role in lifting the US-India relationship from the doldrums, when the Pokhran nuclear tests left ties between Washington and New Delhi in tatters, following Washington's imposing of punitive sanctions, leading to the kind of animosity reminiscent of -- or even worse than -- the Cold War.

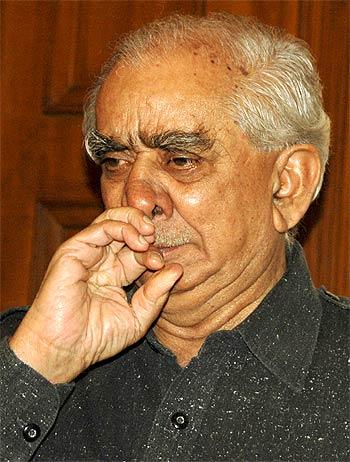

Talbott, who was deputy secretary of state in the Clinton administration, along with then Indian foreign minister Jaswant Singh held a series of painstaking and intensive negotiations that came to be known as the US-India Strategic Dialogue and were catalytic to President Bill Clinton's transformational visit to India in March 2000.

That set the trend for US-India relations as they are today, which, however way one slices it, has never been better.

Asked about the chances of a possible rapprochement between India and Pakistan, Talbott said, "I had the honour of meeting with Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh and National Security Adviser Shiv Shankar Menon. I was impressed by the determination with which the prime minister talked about his desire to leave no stone unturned."

"For reasons we all understand, that determination must be accompanied by a determination to defend India against attacks of the kind it has so grievously suffered," he acknowledged.

"Will the political and security military elite of Pakistan at some point be willing to adjust itself to reality and to jettison once and for all the insidious myth that the greatest security threat to Pakistan's sovereignty and integrity is India," he wondered.

"That is demonstrably not the case," he said. "The greatest threat to the integrity and sovereign of Pakistan comes from two sources -- one to the northeast -- and the other within Pakistan itself. And we have seen that proven time after time and we are seeing it right now."

...

As you look at the state of US-India relations today, following friendly relations with former Presidents Clinton, Bush, and now President Obama, hosting the first state dinner for Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh, his trip to India, would you say this kind of a relationship would have been unimaginable at the time you were trying to get it jump-started after the Pokhran explosions?

Or would you say it was sort of predictable, considering the commonalities and all of the other cliches, etc?

I would say it was somewhere in between. It was certainly not incomprehensible, but it certainly wasn't a sure thing. It was a classic case of having the right leaders at the right place at the right time.

Prime Minister (Atal Bihari) Vajpayee and his key advisers and, of course, I give huge credit to (then external affairs minister) Jaswant Singh, President Clinton, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, National Security Adviser Samuel Sandy Berger with whom I worked very closely during that period, all of them realised that there was something unnatural for both countries during the Cold War period about the tension and the diametrically and irreconcilably different positions that they took on many issues.

That was just something was wrong with that. It didn't make sense. And, to have it continue, after the end of the Cold War, it made no sense whatsoever. At least the other could be explained in terms of non-alignment and the Cold War.

But with the end of the Cold War, non-alignment didn't mean anything anymore. I know that's a controversial thing to say in some Indian circles, since there's still a lot of Indians who take the non-aligned movement very seriously.

So, there was recognition of that at the highest levels of both governments, and despite the fact that it had taken a controversial development, namely the testing, to get us as it were moving, it was quite natural that we would want to move in the right direction.

And President Clinton and Secretary Albright, when they gave me my instructions for starting the dialogue with Jaswant, said we don't want this to be just about the nukes.

Obviously, that is a central issue and let's do everything we can to find some common ground between India and the United States, and Jaswant of course, was willing to do that.

...

How big a deal was President Obama's endorsing India for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council; something the Indians have been yearning for years?

First of all, I don't want to be nitpicky of pedantic, but remember, what he actually said in that very successful speech in the Parliament. He said, I look forward to the day when.... You can be absolutely sure that a lot of time went into the composing of that sentence.

He was clearly taking account of several things. One is that the US can't decide unilaterally who's going to be on the Security Council for obvious reasons; it takes five.

We know that at least one of the five is not going to be an easy sell, namely, China. Leaving aside the specific case of India, expanding or reforming the Security Council is a huge challenge.

I remember Jim Steinberg, who was head of the Policy Planning Staff for a while in the Clinton administration, said, "This is the diplomatic problem from hell."

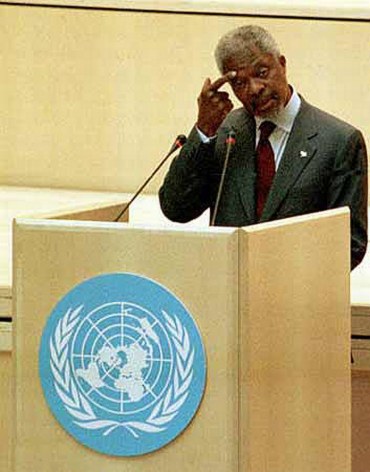

If you remember, Kofi Annan (then secretary-general of the UN), set up a special Eminent Persons Panel to look into it and the panel couldn't even agree on one option.

So, the point is that we should not put all of our eggs in that basket. We all want it to happen. So, let's keep moving in that direction but make sure that India is a member of the board of directors of the world

Obama deserved the applause that he got, but he was picking his words carefully and he was sort of hinting to Indians that they should not make this the be-all and end-all.

...

The US-India nuke deal was the centerpiece of the Bush administration and the Indian American community lobbied to make it happen and to first get the imprimatur in both the House and Senate.

But during those deliberations, you were one of those who were strongly opposed to it, saying it compromised US's nonproliferation commitments.

Now that so much water had flowed under the bridge and it's a done deal -- though yet to be fully implemented -- do you still have strong feelings about it?

Let me clarify my own position on a couple of points. First of all, my criticism was directed not against the Indian government or the Indian side. My criticism was of the Bush administration's policy.

I felt that the wiser course was the one that the Clinton administration had embarked upon.

We in the Clinton administration never took the position that India had to, must, or would become a signatory non-nuclear weapons state of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. That was moot.

When the desert shook that memorable day in May of 1998, that issue was moot. India was a nuclear weapons State. So, the starting premise for the Clinton administration's position was how could India still contribute to the cause of a firm and effective global nonproliferation regime.

My criticism of the Bush administration was that they essentially weakened the global nonproliferation regime in the deal that they ultimately signed. But once it was signed, I never had any doubt of its implementation because then that became a fixed reality and it wasn't going to change.

So, I was definitely in favour of the implementation. I was, however, concerned that there were unrealistic expectations about the benefits that would flow to both sides as a result of the deal being passed, and yes, there have been disappointments.

Does that answer your question?

When you say there have been disappointments, presumably you are referring to the nuclear liability law passed by the Indian Parliament, which has put a damper on the deal?

Yes, the disappointments on both sides. I was in Mumbai and Delhi on the eve of President Obama's trip, and I talked to a lot of American businessmen who had showed up and some of them were residents in India.

They said, "You know, we've got to do something about this liability law."

And, of course, the United States is not the only country whose private sector has difficulties.

Even the Indian private sector has expressed its deep concerns?

The Indian, Russian and French sectors. But my point there is that this is a democracy and there is a separation of power between the legislative and executive branches and we have seen plenty of examples in Washington.

And there are going to be plenty of other opportunities to make progress.

...

The over $10 billion worth fighter aircraft deal did not go through for the American companies, even though Obama sent a personal letter to the Indian PM, and India opted to choose between the European aircraft.

India also abstained on the UN Security Council vote on the Libya No-Fly Zone, criticised North Atlantic Treaty Organisation along with its BRIC partners, just to mention a few tweaks inimical to the US.

Does this mean India can never be a strategic ally of the US, but only a strategic partner? And does all of this also have something to do with the recent WikiLeaks revelations, and an attempt to stave off criticism that it has become completely pro-US?

Can we put the WikiLeaks issue aside for a moment and deal with the rest of your question?

First of all, at the risk of being a little bit focused on the semantics here, there is diplomatic and precise distinction to be made between an ally and a partner.

If India were an ally of the US, there would be a treaty of alliance between us, like the one between us and Japan, Korea, and our NATO allies. We are not now, and may never be allies in that sense.

One reason we may never be or not, in the any foreseeable future, is because there is still a huge constituency in support of India's non-aligned status, despite the fact that I would say that non-alignment and the non-aligned movement is very much an artifact of the Cold War.

I remember having a conversation with Natwar Singh when Congress was out of power and him saying to me that the proudest moment of his career was being secretary general of the non-aligned movement. That sticks in my mind. I took that as a sign that there are still a lot of Indians who take non-alignment seriously.

The fact is, we are strategic partners and none of the examples you have cited suggest otherwise. Take the aircraft deal; you win some, you lose some. India is going to make its own decisions for its own reasons, which are going to include technical considerations.

Second, India understandably wants to diversify its source of military equipment for all kinds of reasons, including probably uncertainty about what US policy or US legislation will be in the future.

Third, there are I see estimates as high as $200 billion that India is going to be spending in years to come, so that means there is plenty more business to be done, and plenty more opportunities for American companies to have in on that business.

But a more general point here is the United States has had lots and lots of disagreements with its allies, not to mention its partners over the years.

Take the tension between the NATO allies that Secretary Clinton has been spending a lot of time with on how to prosecute the No Fly Zone in Libya, the US policy with respect to Iraq.

You know, countries are in some ways like human beings. I have a lot of friends, colleagues, the personal equivalent of allies, with whom I disagree all the time and that comes with the territory not least, because, we, within our countries have debates over these issues. Too much has been made of these issues. Did you mention Iran as well?

...

I am coming to Iran, that's a whole separate question I had in mind...

We'll deal with Iran separately. WikiLeaks, you'd be the better judge of that than I. WikiLeaks is an ambiguous phenomenon. It has two sides to it. On the one hand, it is a disgrace and an outrage and a colossal case of mismanagement of information by the US government that was allowed to happen because there are a lot of things in that can only be dealt with effectively if they remain secret.

At the same time, none of us have read all of the WikiLeaks because the volume is so large. But the New York Times and other publications have been putting them out in sort of digestible chapters.

It's a good story. And, I've always been a fan of the Foreign Service and the way our diplomatic establishment works I know it from the inside, and I've been party to plenty of stuff that's secret.

I believe there are good professionals doing the job and it is really unfortunate that the revelation of these cables and conversations has embarrassed foreign friends.

That's regrettable, but the story that it tells, is one that we can broadly as Americans, be proud of.

Coming to Iran, do you consider India's close relations with Iran becoming a major irritant, which could spill over in the Congress because even India's best friends never fail to mention their deep concerns over this.

And, especially now, with the new configuration in Congress, can this morph into the kind of contentious issue that could make the US retreat to the old you-are-either-with-us-or-against-us kind of foreign policy?

First of all, I am going to be worse than your most picky editor here. Again, I am going to pick up on one word and take issues with it. I wouldn't describe the relationship between India and Iran so much as close as pragmatically driven, and it's one of engagement with Iran.

So, I do not share the view that it is ipso facto bad or wrong for a country -- India or otherwise -- to have to engage with Iran. It is understandable in India's case for the reasons that you mentioned.

Being on the receiving end of energy supplies and for lots of historical and geopolitical reasons, it would be unreasonable and ignorant to take the position that India should boycott any relations with Iran.

How is India using that relationship? I happen to know because responsible Indians have told me that India has lots of issues with Iran. The fact that it has diplomatic and other ties with Iran, does not mean that Indian officials and diplomats aren't very candid with the Iranians.

The United States comes by its neuralgia honestly where Iran is concerned. I mean, Iran is exceedingly dangerous. It's a complex country, currently dominated by a very dangerous regime in multiple respects and it isn't just its nuclear weapons ambitions.

It's also its active sponsorship of international terrorism, an issue that has much resonance in India if not in the US. And, it is also a country that brutalises its own citizenry in many ways. I said it's a complex country and in some ways of course, it inherits a great civilisation.

It has a very cosmopolitan population, it's plugged into the world, it has a degree of democracy well beyond those of most of the Arab world, and my own guess is that sooner or later the more positive elements of Iranian society and polity will prevail over the execrable Ahmadenijad and what he represents and the clerics, which are not identical phenomena by the way.

So, it's potentially and in some ways, actually useful for the United States to have the closes possible contacts with India on the subject of Iran, because India is a reservoir of deep knowledge about Iran.

...

Are you optimistic or pessimistic of any rapprochement between India and Pakistan, considering Pakistan's proxy wars against India through its terrorist assets?

We've talked a lot about a number of important issues, but this is one of the most important and certainly one of the most sensitive. Let me start with a sincere positive, that is, that there is a ray of some light in a fairly dark corner that the Pakistani leadership under now two leaders -- the Musharraf regime and the current more democratic regime -- that there have been contacts and quite promising contacts or at least what could have been promising contacts. It is of huge credit to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh as it was to Vajpayee before him that they have been willing to kind of go the extra mile.

I had the honour of meeting with Singh and National Security Adviser Shiv Shankar Menon, and I was impressed by the coherence and the conviction and the determination with which the prime minister talked about his desire to leave no stone unturned.

There have been moments when it looked like there was an interlocutor on the Pakistani side. The onus for how this question is going to be answered lies with Pakistan.

You referred to the execution of Osama bin Laden by American forces; something that I heartily welcomed and approved of. It was entirely justified. It happened in a virtual, if not literal, annex of a cantonment of the Pakistani military.

It simply strikes me as unbelievable, that bin Laden was able to live in that compound under those conditions without not only the knowledge, but without the support of important elements in Pakistan.

And, not only is that an outrage against the US, given this man's responsibility for the worst attacks on our territory we've suffered since the British burned Washington -- leaving aside Pearl Harbour.

The fact that there are whole vast regions of Pakistan that are not really under the control of Islamabad -- Rawalpindi is another question -- but that means that Pakistan has an existential problem and the address, the origin of that existential problem is not in New Delhi, it's not in India, it's in Pakistan itself.

The next generation of Pakistanis have to come to grips with this in the terms I am talking about, or not only is the danger that my colleague and friend Steve Cohen mentioned, but remember, he put it in a conditional, he said if Pakistan is not able to deal with this issue, one of two things will happen -- unending conflict.

I wouldn't call it a 100-year war, but I would say unending conflict or the dissolution of the Pakistani State.

...

How much of a danger will it be to the US, to India, or the world, if Pakistan fails? Because apart from the fact that it's got this existential threat of such overwhelming extremism gnawing at its very fabric, it's also got a 100 nukes.

Just huge, huge, huge, and we are still counting (the number of nuclear weapons Pakistan may have). I mean, this is sensitive information, but I can tell you that there is an expectation that Pakistan -- if the current trend continues -- is going to replace the United Kingdom as the number five quantitatively nuclear weapons State on the planet.

If the trend then continues, it could replace France as number four. And, of course, I realise this is an issue much on the minds of Indian strategic planners.

I guess it not just a question of simply replacing Britain or France as a nuclear power with more nukes, but that a failed Pakistan State with this kind of a nuclear arsenal, the ramifications coupled with radicalisation would be unimaginable?

Absolutely. The fact, as we have been reminded by the all-too timely demise of Osama bin Laden, there is some kind of nexus between the most dangerous terrorist organisation on earth and what are supposed to be responsible people in the security establishment of Pakistan.