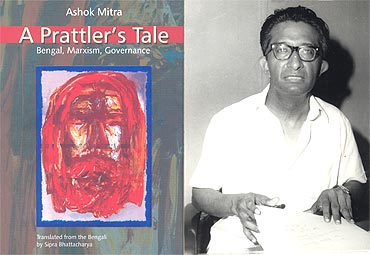

The Left Front is still struggling to fill the ideological vacuum created by the death of Jyoti Basu, veteran Marxist and the longest serving chief minister in India, on May 17 this year. On the occasion of his 96th birth anniversary today, we present an excerpt from an autobiography by former Bengal finance minister Ashok Mitra.

The eminent economist recalls his bitter-sweet association with his fellow comrade and former boss, and the latter's penchant for clipped sentences, good food and note-taking. Incidentally, Mitra, who also served as the chief economic adviser in the Union finance ministry and as a member of the Rajya Sabha, resigned from the Bengal cabinet in 1986 over differences with Basu.

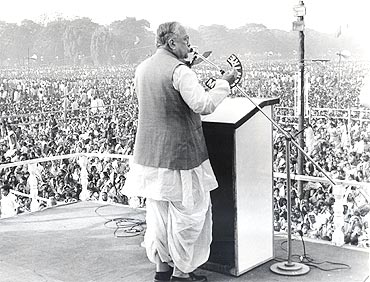

I saw Jyoti Basu from close quarters during those years and so am in a position to share some experiences. I have heard many of his political speeches and am well acquainted with his fondness for half-finished sentences, the fireworks of irony, the purposive intrusion of humour which makes others laugh but he himself remains impassive, and -- yet, taken together, there was a thread of solid logic running through the speech, rendering it altogether convincing.

However, his diction was quite different in the Writers' Building's corridors of power, never mind whether he was speaking in English or Bengali: no hint of any irony or sarcasm, the main issues concerning the subject under discussion were expressed in clipped sentences. I found this ease amazing, this simple way of explaining things. Perhaps he had not read ahead much about the topic under discussion; that did not however matter.

Whether it was something to do with finance or about irrigation, about drainage of excess water or the building of roads, he cut through straight into the heart of the problem. This was proof enough to me that it was not necessary for a practicing politician to carry any baggage in his mind beyond ample common sense.

I have had the opportunity over almost half a century to meet many political leaders, both at the Centre and in the state. I never found anyone with Jyoti Basu's sharpness of mind. The only possible exceptions were Indira Gandhi towards the middle of her political career, and -- this will surprise many -- Jagjivan Ram, and among the state chief ministers, Mohan Lal Sukhadia.

On many matters, I agreed with Jyoti Basu, on many matters I did not. There was never any lack on my part in giving him the respect that was his due. On the other hand, when I felt the need to express a point of view that differed from him, I did so freely. I argued when necessary, I wrote sharp notes in the files. But if he were not willing to enter into a further discussion, for whatever reason, it would not be possible to proceed.

I must nonetheless put it on record that despite his being thirteen or fourteen years my senior in age, he too never ever failed to accord me the courtesy a human being expects to receive from another. In 1986, a difference of opinion on a particular issue made me decide to leave the secretariat and sit at home; even on that occasion there was no lapse of mutual courtesy, nor any expression of rancour.

Reproduced from A Prattler's Tale: Bengal, Marxism, Governance, by Ashok Mitra, translated by Sipra Bhattacharya Samya 2007, Kolkata. For more information, please visit: https://www.stree-samyabooks.com/

This does not mean that Jyoti Basu was not rough with me. I remember an incident. It was a meeting of the state secretariat of the party. I had been called for discussion on a particular issue. My views were radically different from Jyoti Basu's -- the two of us argued for about an hour, others present remained more or less silent spectators. I was adamant, refusing to yield any ground.

All of a sudden, Jyoti Basu turned towards me, bent forward, low, as if in mock greeting and said sharply, 'I beg your pardon a thousand times over. I had forgotten that you are an intellectual. What we common folk can understand in thirty seconds, it takes intellectuals like you more than an hour and a half to comprehend.' He uttered the statement with such aplomb that I burst out laughing.

Back once more to 1977. When the budget was presented, this was probably the first time that the minister himself had prepared the budget speech in both English and Bengali. We were still busy building dreams. The budget speech talked of many commitments and made many promises, especially about rural planning.

We had already begun intense discussions about overhauling the panchayat system and vitalising the three-tier structure through the basis of democratic elections. The speech threw some indicators about this coming move. There were also detailed proposals for re-organising the sales tax structure along with suggestions for some new taxes.

One particular proposal made me the target of ire of a section of film directors: I had raised the price of tickets for colour films way above that for black-and-white films. Black and white films, I argued, were shown mainly in the districts and rural areas; it would be unethical to increase the tax in this case. But for urban and metropolitan cinemagoers, interested in watching Hollywood movies or the song-and-dance spectaculars from Bombay or Madras, some increase in tax was perfectly justifiable.

The protesting directors were worried because they had just begun to work in colour; in case the tickets were made expensive, people would not, they feared, come to watch these films. I could not quite accept the argument. However, partly to placate them, I promised to set up in Calcutta, a state-of-the-art colour film processing laboratory, which would help speed up processing. I received much support from the party and film technicians and workers in breaking the resistance of the film directors. The colour film laboratory, Roop Lekha, is, I understand, going strong.

Another issue related to the budget, gave rise to a misunderstanding with some of my colleagues. It was necessary to maintain a degree of secrecy in regard to the proposals in the budget before it had been presented and the taxes announced. The fiscal proposals, in my view, could only be discussed beforehand with the chief minister.

With fiscal proposals impinging on their area of activity, other ministers were upset, but nothing could be done about it. Not that the matter did not deserve a close reappraisal. In the budget for 1978-79, we introduced an unemployment allowance. It was the first of its kind in the entire country.

Even though the amount of the allowance was very small, it provided a recognition of society's responsibility towards its unemployed. I had high hopes that against payment of the allowance, unemployed youth would take part in government-sponsored development projects, conceivably twice a week, or eight days a month.

Had I been able to discuss the matter with the other ministers before making the announcement in the budget, this part of the plan could perhaps have been prepared in a better manner. But I could only talk to them in innuendos. This, I suspect, roused resentment, and I too remained dissatisfied with the scheme.

There were, of course, other problems in ministerial functioning: several of those who had been made ministers had spent their whole life so far in managing peasants or workers; they had spent years in jail or had been chased by the police; they had an inordinately simple way of living. They took time to adjust themselves to ministerial existence. I think it was because of the unease they felt that they never really found the work in Writers' Building to their taste.

They became dependent either on senior civil servants or on lower rank government employees who were their political comrades and with whom they would discuss departmental matters and reach their decisions. This was a Catch-22 situation: if they listened too much to senior officials, their comrades among the lower ranks would be alienated; if they signed the files with nothings as advised by the latter, the senior bureaucracy would take umbrage.

Many of these gentlemen, despite being inspired political leaders, and with memorable track records in popular movements, were therefore not much of a success as ministers.

It was not always easy to discuss these and similar issues with Jyoti Basu. He listened but he was disinclined to enter into any lengthy discussions. The reason, I analysed, was that the people I was trying to tell him about, albeit in a cautious, roundabout way, were important politically, and he had to be discreet discussing them with one who carried no weight in the party organisation. It was, however, possible to discuss these things much more openly with Promode Dasgupta in (CPI-M's Kolkata headquarters) Alimuddin Street.

(Editor's note: Pramode Dasgupta, who served as the powerful state secretary of the Communist Party of India-Marxist for many years, is considered as one of ideological architects who built up the party block-by-block after its split from the Communist Party of India in 1964. During the party's teething years, Basu became the public face of the CPI-M in electoral politics, while Dasgupta remained a grassroots leader till the end)

Promodebabu never stepped into Writers' Building, but he could quickly grasp the administrative difficulties confronting his ministers from time to time. A straight talker, he never hesitated to call a minister and criticise the functioning of his department. When he thought it necessary, he would pull me up, like he did the others. I suspect that only with Jyotibabu he felt inhibited to express himself freely.

Even when he had doubts and questions, he never discussed matters of administration with Jyoti Basu unless there was a third person present in the room. Or he would wait for the meeting of the party secretariat. I found it intolerable that the valuable time of the chief minister was often wasted in useless chores.

Sometimes, responding to the importunings of self-serving persons, Jyoti Basu would go on meaningless trips; whereas, often he was unable to give us a time to discuss really serious issues. I presented a set of proposals to Promode Dasgupta about how the chief minister's office could be made to function in a more effective and disciplined matter; how Jyotibabu could be rescued from the clutches of an exploitative minister belonging to a lesser party in the Left Front; how to give a fillip to development activities, and how to improve coordination between the different departments.

Promodebabu did not disagree with me but he insisted that I bell the cat. I understood his dilemma and stepped back. Snehangshu Acharya was equally close to both Jyoti Basu and Promode Dasgupta. I believe that when sensitive issues were involved, Promodebabu requested him to intercede with Jyoti Babu.

In the undivided party, Jyotibabu had been the secretary of the state committee for a number of years. A great change in the organisational frame of the party took place following the formalisation of the split in the party in 1964. New workers had been inducted in the districts and the character of the party was qualitatively transformed. For whatever reason, a considerable social distance separated Jyoti Basu from the other party leaders and party cadres, which was not at all the case with Promode Dasgutpa.

The latter knew literally thousands of party cadres, even workers from little-known villages of faraway districts. He kept himself informed about their families and their personal problems; he recognised their faces and knew their names. Jyoti Basu's personal limitations in such matters were an open secret; he had an excellent equation with the older comrades, but many of the new generation were unknown to him.

(Editor's Note: Snehangshu Acharya, who served as the advocate general of West Bengal, was considered to be close to the Bengal CM and one of the few Leftists he confided in)

Once, when I was sitting next to him on the treasury benches in the assembly and a member was speaking from the other end, he turned towards me to enquire which party the member belonged to. I had to inform him with some embarrassment that the member was from his own party; he was Jyotibabu's comrade.

I was also most impressed by another quality that Jyotibabu possessed. He was an exceptionally organised human being. Whether it was a small political meeting in a village or town or the chief minister's address in the state assembly, he invariably noted down the main points to be mentioned in numerical order, so as to ensure that he did not leave out any important point. One day I noticed him jotting down in English the points for the speech that he was about to make in Bengali a few minutes later.

Noting my astonishment, he said with a smile, 'What to do, I have to do my jottings in English, my education isn't as complete as yours!' I still have not got over my astonishment that he spoke without stopping for hours on end, in fluent and idiomatic Bengali, but after referring to points noted in English!

Something equally worthy of mention: despite the mask of solemnity Jyoti Basu wears, he is fond of light conversation with his close friends. He likes to share jokes and gossip about trifles. No matter what a person's dress, appearance or social status might be, he can be sure of courtesy from Jyoti Basu's end. This is just not a matter of Bengali manners; according every individual adequate respect is for him a matter of instinct.

One of the media's contribution to misinformation, Jyoti Basu is stated to be particularly fond of the company of industrialists and businessmen. Nothing could be further from the truth. Jyotibabu likes all kinds of food, from continental to simple, ordinary Bengali fare, even the rice mixed dal, salt and chilies found in the humble home of the poorest worker or peasant. Wherever he was he would eat with relish whatever food was served. It is no longer possible for him to be as sociable as he once was, but I can recall that even fifteen years ago, he would sit down with others at feasts that followed, say, a child's first rice-eating ceremony or a wedding, and enjoy being and eating with people.

True, Jyoti Basu was quite unlike Promode Dasgupta. The former is reserved by nature, giving little indication of the emotion or feeling passing through him at a particular moment. This could be on account of his family background. Promode Dasgupta, on the other hand, had reached the top echelons of the party by working his way up the latter. He was born in an archetypal Bengali middle class home; from the time he was a teenager, he was involved in what was known as nationalist activities. He had spent his youth with the so-called terrorists. From then on, his family ties were as good as non-existent.

The party commune was his home and family. The quality of proximity to party cadres at different levels would take one's breath away. Jyoti Basu was the scion of a wealthy family; as a child he had studied for a year in a Loreto convent -- yes, in Loreto, a school for girls that had a kindergarten that took in boys -- and later in St Xavier Collegiate School, both elite institutions. Subsequently, he did his undergraduate studies at Presidency College, and went on to England to study law. Even as he was preparing to be a barrister, he was taking lessons in socialism from Harry Pollitt and Rajani Palme Dutt.

The ground was prepared, Jyoti Basu himself avers, in Calcutta itself. One of his uncles was so loyal to the British that the foreign masters elevated him from the post of a junior munsif to that of a judge of the Calcutta high court. A tribunal had been set up to try the young men accused of terrorist activities in the early 1930s, which the uncle headed. This uncle would bring home a load of socialist books found in the dens of the young men on trial. Jyotibabu claimed, with a modicum of pride, that it was by reading those books that he became a communist by conviction.

(Editor's Note: Considered stalwarts of the Communist Party of Great Britain, both Politt and Dutt had served as the general secretary of the party. Basu has often mentioned that he owed the transition in his political orientation to the interactions he had with the duo during his student days in Britain.)

Reproduced from A Prattler's Tale: Bengal, Marxism, Governance, by Ashok Mitra, translated from the Bengali by Sipra Bhattacharya Samya 2007, Kolkata. For more information, please visit: https://www.stree-samyabooks.com/