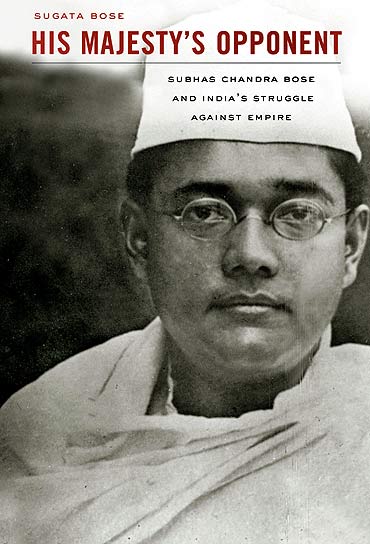

Sugata Bose, author of freedom-fighter Subhas Chandra Bose's biography His Majesty's Opponent, talks to Arthur J Pais about his grand uncle, one of the freedom movement's most intriguing figures. The first of a four-part interview.

Tomorrow: Emilie Shenkl's letters to Subhas Chandra Bose

A few pages into His Majesty's Opponent, and you may forget that this book is written is by a renowned Harvard University academic Sugata Bose. For here is a biography of one of the most intriguing and powerful men in 20th century India, Subhas Chandra Bose, written with energy and without sacrificing the historical details.

Netaji was an uncle of Sugata Bose's father, Sisir Kumar Bose, a distinguished pediatrician and a freedom-fighter. The Harvard historian does not hesitate to execute his duty as a historian.

For instance, he thoroughly examines Netaji's alliance with the military rulers of Japan and asks the question whether Netaji had embraced rightwing military ideology. He revisits the records that show that Netaji did indeed die in an accidental plane-crash.

And in the following interview, Professor Bose thinks over why many people refused to believe in the air-crash account and why some perpetuated the myth of a 'deathless hero' many decades after the plane-crash.

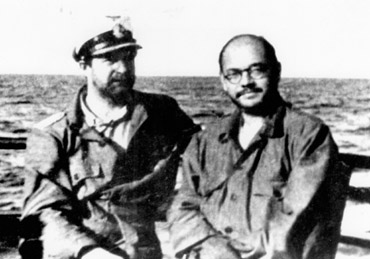

In parts the book, published by Harvard University Press, reads like a thriller, especially when dealing with Netaji's daring escapes from British clutches. There is a spirited account of a secret submarine escape, and riveting material on Netaji's complex political strategies.

But above everything else, the book offers an intimate portrait of Netaji not only as a revolutionary leader but also a loving husband, a man of letters, and an untiring believer in communal amity.

It is also a great account of a love story and the story of an Austrian wife who never remarried and brought up her daughter -- Netaji's only child -- single-handedly, despite having to endure many hardships.

The book also reveals how the Bose family reacted when they came to know of Bose's secret marriage.

Several academics including the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen have praised the book.

'Larger than life, more profoundly intriguing than the myths that surround him, Subhas Chandra Bose was India's greatest 'lost' leader,' writes Homi K Bhabha, Harvard professor, in a blurb. 'In a remarkable narrative that pairs political passion with historical precision, Sugata Bose has beautifully explored the character and charisma of the man, while providing an elegant and incisive account of one of the most important phases of the struggle for Indian independence.'

Sen muses: 'Subhas Chandra Bose was perhaps the most enigmatic of the great Indian leaders fighting for independence in the twentieth century. This wonderful book makes a major contribution to the understanding of the political, social and moral commitments of Netaji, the great leader, as he was called by his contemporaries.'

And New York University professor Arjun Appadurai applauds the biography, calling it 'remarkable.' It 'places Subhas Chandra Bose fully in the context of Indian and world history. It should be read by everyone interested in the end of the British Empire.'

This is the kind of book that you read in about two days and wonder, was it really 448 pages long?

The following interview was conducted mostly in the Harvard University office of Professor Bose, with a few follow-up questions answered through e-mail from Harvard and the city of London where Bose was giving a lecture.

...

One reason was that, even though Netaji always said that his family was coterminous with his country, I was aware that by an accident of birth I was a member of the family. So I kept putting off writing his life.

But there was another reason. I felt that I could only do justice to what I have described as the global odyssey of Subhas Chandra Bose after I had really gained mastery over global history, European history, Asian history and Indian Ocean history. I have told the life of Netaji as very much a part of world history in the first half of the 20th century.

So I think it was only appropriate that after I had published my book A Hundred Horizons that I should do a full-fledged biography of Netaji.

I always knew that I could do a book when I was jointly editing the Collected Works of Netaji with my father Sisir Kumar Bose from 1992 onwards. But I wanted to do a very major and significant book.

It was intuitive. I really felt that the time had come for me to write this book a few years ago. I could have done a book on Netaji many years ago, but this kind of a book is what I felt impelled to do and I really wrote it during my year of sabbatical leave in 2009-10.

This book has many layers. Deep scholarship and historical revelations apart, it also reads in part like a good thriller. Not to forget an emotional story.

There are certain chapters or sections of the book, which probably read like a thriller because Netaji's life was a thrilling adventure. As he prepared to resign from the Indian Civil Service in 1921, the response from the innermost corner of his heart that he heard was: "The way to your happiness lies in your dancing around with the surging waves of the ocean."

So when I was writing about his escape from India in January 1941 -- it was my father Sisir Kumar Bose who drove the car in which he left his home on Elgin Road in Calcutta -- or when I was describing the perilous 90-day submarine voyage between February and May of 1943, I simply had to do the research and tell the story well.

What emerged then is, I hope, a gripping narrative. But there are other parts of the book, which are either more reflective or analytical, and in some parts there is a good bit of emotion.

What had you heard from your father about the 1941 escape and what more did you discover when you were researching this book?

I heard the story of the great escape from my father as a child. But while researching the book I also consulted fascinating British documents in London.

The governor of Bengal, John Herbert, had thought he would deploy a "cat and mouse" policy in relation to Subhas Chandra Bose and re-arrest him as soon as he recovered his health following his hunger strike in prison.

"If he resorts to hunger strike again," Herbert wrote to Viceroy Linlithgow, "the present cat and mouse policy will be continued, and its employment will serve both to render him innocuous and to make him realise that nothing is to be gained from a series of fasts."

The British files show there were at least 14 secret police agents keeping watch on Netaji; they were numbered AS95, C207, etc. Netaji told my father that they had to work out a fool-proof escape plan.

In the end, the British intelligence officers were left shame-faced and bewildered. Herbert was sharply rebuked by Linlithgow. One police officer named Janvrin realised that Bose would never "cease to strive his utmost to achieve what has been his life's aim -- the complete independence of India".

...

My mother had supported my father in preserving the best traditions of the freedom movement ever since he set up the Netaji Research Bureau in 1957. She accompanied my father on two important research trips through Europe in 1971 and across Asia in 1979.

She wrote two books in Bengali based on what she found during these travels -- Itihaser Sandhane (In Search of History) and Charanarekha Taba (In Your Footsteps). She is an authority on Netaji's overseas activities and her vast knowledge was of great help to me in writing my book.

Tell us a few important things about the submarine journey and the new things you came across about it during your research.

Netaji's sole Indian companion on the submarine voyage, Abid Hasan, used to visit and stay in our home as I was growing up. On one of his visits my parents and I taped a very detailed interview with him on his time with Netaji in Europe, on the perilous 90-day submarine voyage, and finally in Japan and Southeast Asia.

On the submarine Netaji used to dictate speeches to Abid Hasan that he planned to deliver in Southeast Asia, including one to the women's regiment of his dreams. One day when they were up on the bridge of the vessel, Hasan asked Netaji to name the worst fate he might suffer. Netaji answered: "To be in exile."

I also found interesting German and Japanese documents. Netaji had written to the German foreign minister: "There is a certain amount of risk undoubtedly in this undertaking, but so is there in every undertaking. At the same time, I believe in my destiny and I therefore believe this endeavor will succeed."

His transfer on a rubber raft in the Indian Ocean from a German to a Japanese submarine was a military feat unique in the annals of the Second World War. The Japanese submarine, I-29, in which he was taken to Sabang in Sumatra was later sunk by the Americans in July 1944.

What are some of the things that surprised you most about Netaji during your research and editing of his works?

Netaji is popularly regarded as the great warrior hero. I found while editing his collected works that he was a farsighted thinker with a philosophical bent of mind.

He was writing about the future social and economic reconstruction of free India in his essays and speeches. He was also someone who was introspective, constantly analysing himself, particularly when he was in prison or in home internment.

And I found he was dealing with his long years of imprisonment with a balance of stoicism and humour. He wrote beautiful letters to his sister-in-law about life in jail or and to his elder brother, Sarat Chandra Bose.

I found it fascinating that most of the letters to Bengali women were in Bengali and the letters to his brother (until his 1941 escape) were in English. I also found he was reading voraciously whenever he was in prison or exile (he went to prison 11 times and nearly 11 years of his life were spent in prison or exile) or in home internment, making copious notes on books he read.

For example, I write about how he was fascinated by Irish history and literature, writing down in his Mandalay prison notebook beautiful poems by PH Pearse who was killed after the Easter Uprising against the British in 1916.

Pearse's lines about a rebel who came of 'the seed of the people that sorrow' must have seemed especially poignant to Netaji:

I say to my people that they are holy,

That they are august despite their chains,

That they are greater than those that

Hold them, and stronger and purer...

He also had a notebook in which he transcribed his favourite songs, several of them composed by Rabindranath Tagore.

...

We are marking the birth anniversary of Tagore. What kind of relationship did he have with Netaji?

Even before Tagore won the Nobel Prize in 1913, the 15-year old Subhas wrote to his elder brother Sara "how indifferent Bengal had been in showering laurels upon him" while foreigners "extolled him as the greatest poet the world has produced".

In 1921 Subhas travelled back from England to India on the same ship with Rabindranath and discussed Gandhi's movement of non-cooperation. Nearly two decades later, Tagore provided solid support to Subhas Chandra Bose during his conflict with the Gandhian high command of the Indian National Congress in 1939.

Rabindranath hailed Subhas Chandra as "Deshnayak" ("Leader of the Country") in January 1939. He confessed that he had felt "misgivings" in the uncertain dawn of Subhas Chandra's "Political Sadhana (quest)". But now that he was revealed in the "pure light of midday sun", there was no room for any doubt. "When misfortune from all directions swarms to attack the living spirit of the nation," Tagore declared, "its anguished cry calls forth from its own being the liberator to its rescue."

"I may not join him in the fight that is to come," the 78-year-old poet wrote. "I can only bless him and take my leave knowing that he has made his country's burden of sorrow his own, that his final reward is fast coming as his country's freedom."

We seem to know more about Gandhi and Nehru as writers and correspondents than Subhas Chandra Bose.

Yes, even though Netaji wrote quite as much in prison in the form of letters and he wrote his two major books while in exile in Europe between 1933 and 1937, The Indian Struggle was written by him in 1934 when he was in European exile and I have shown in my book how well it was received by the British press and the European literati. A few British reviewers obviously had difficulty with the point of view he was expressing, though they admired his clarity of vision.

When you think of his unfinished autobiography An Indian Pilgrim, he wrote 10 chapters in 10 days while he was in Badgarstein in Austria in December of 1937 and I think it is a beautiful, analytical and introspective autobiography.

There is only historian, as far as I know, and a great one at that, Ranajit Guha, who actually appreciated how beautiful that incomplete autobiography is and even in comparison to Nehru's really great autobiography.

I do have a lot to say comparing Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru. They were very good friends in the late 1920s and the 1930s.

What I do also point out in the book is that Subhas's discovery of India took place very early in his life when he was a teenager, while Nehru's discovery of India took place when he was much older once he found himself among the peasants of Uttar Pradesh at the time of the Non-Cooperation Movement.

So the similarities and differences between the two young radicals and left-leaning leaders form an important theme in the book.

I was hugely and very pleasantly surprised as a historian when, in 1993, my grand aunt Emilie (Subhas Chandra Bose's wife whom he secretly married in Austria) made available some 165 letters written by Subhas to her.

The last major biography of Netaji was published in 1990. Brothers Against the Raj by Leonard Gordon is a very good book but unfortunately he did not have access to the correspondence between Subhas and Emilie.