'My boss was a woman. Not any woman, she was a demanding, rude and foul-mouthed creature whom I liked immediately,' says Aakar Patel.

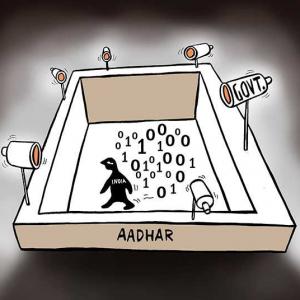

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

I began working at the age of 19, in the family textiles business in Surat. The factory was located in Ankleshwar, about 80 kilometres or so away.

This factory texturised yarn, which meant that we processed polyester that was produced by companies like Reliance and made the plasticky thread (called partially oriented yarn, or POY for short) more absorbent and cotton-like.

We also owned looms in the city of Surat, and these looms were where some of the yarn we processed was woven, while the bulk of the Ankleshwar factory’s output was sold to other weavers.

The routine I followed was to go in the morning to the office and look at some sales and purchase matters. This involved telephoning clients and suppliers, and negotiating rates for sales and purchase.

The language of business was Gujarati. Sometimes, when one was dealing with one of the many thousands of Marwaris and baniyas who have settled in Surat, it was Hindi.

Occasionally, the work involved visiting the clients and suppliers (who are called 'parties'). This happened particularly when there was a complaint from a party about 'quality', which meant that they wanted to cut some money out of their dues, and one had to go over to take a look at what the problem was.

This was particularly difficult because we all produced 'grey' (that is, uncoloured) yarn and fabric, which all looks the same.

There was absolutely no way of knowing whether the offending material was from our factory or from elsewhere and whether the problem was in the texturising or the weaving or elsewhere.

The business, like all business in Surat, including diamonds, real estate and textiles, ran a lot on trust and, of course, trust is often abused in business. That was also our fate.

The other people in our office were all male: A handful of accountants, sales people, clerks and so on.

Except for the person cleaning, everyone was in a white collar job, though, of course, the salaries were nowhere near where they would be in a proper city.

At the factory almost everyone was in a blue collar job. There were trained men, called karigars, a word that translates as artisan, but in this instance it meant people who were skilled in one particular aspect of the textile trade. The others were untrained.

They came in two categories, one lot were called 'helpers', because they helped the karigar in some fashion and had some training.

The others were labourers who carried stuff, mostly the cartons of yarn (weighing around 20 kilograms each), from here to there.

This second category included some women, but these I never spoke to and never engaged with in any way.

Those of you who are from small towns or have worked on factory floors will know what I mean.

I had once encountered a woman in a workplace, and this was in an office with a reception (a novelty), behind which sat a lady manning the telephones.

Anyway, I was part of this family business for six years, when it finally went bust around 1994 or so.

We blamed the opening up of the economy by Manmohan Singh, though our incompetence may also have contributed.

With no real education and no experience of value and certainly no capital, I had few options in Surat.

Also, I was interested in working in a modern office and, having read a book or two, to work in English. That was my dream and it wasn't going to happen in Surat, where almost nobody spoke the language and almost nobody was interested in it (very few are even today, a quarter century later).

I came to Bombay, as it was then called, and began looking for work in the import-export business. This 'training' involved going along with a man to the city’s ports and getting goods released.

Other than noticing that the office staff took bribes without any joy, as entitlement, I did not learn much in the weeks that I did this.

Then one afternoon, quite serendipitously, I landed a job as a journalist, a development that shocked me and my family.

Now this was a different workspace than I was used to.

I had zero experience of working with women, and the media, as some readers will know, is slightly less gender unequal than other sectors.

Some of my female colleagues were dazzling writers, and on my first day I took a look at the text one of them (a feature writer named Genesia Alves) had just banged out.

I was astonished at how graceful the prose was, shorn of cliché and flowing like water.

To top it all, my boss here was a woman. Not any woman, she was a demanding, rude and foul-mouthed creature whom I liked immediately.

She disabused me very quickly of my ignorance and not a little of my stupidity.

She was an editor and, in those days, and perhaps even now, the newspaper editor was a tyrannical figure with absolute authority.

She/he could hire and fire at will, could promote and transfer at will and could make careers through the apportioning of assignments and beats.

In my years as an editor, I will admit that I also often acted as a tyrant. Though I enjoyed it then, I would have, or I hope I would have, done it differently had I known then what I know now.

After my editing stints (the last being in a Gujarati newspaper), I ran a services business for some time and at this I was a little more successful than I had been with manufacturing.

In fact, it afforded me the luxury of retirement at 40, where I remained for five years, and would have remained, had I not been offered the opportunity of working in the non-profit sector, where I am today.

This is again a space with a unique working culture.

There are things like affirmative action and consensus, that will be laughed at in the private sector.

It is not a perfect workspace, of course, but it tries to be better from within.

There is an insistence on parity in terms of gender, caste, faith and disabilities and if this parity does not exist (and it doesn't) then the organisation attempts to change this.

My colleagues will perhaps disagree with me, but I think it has made me more open of mind.

I knew nothing of non-governmental organisations when I took up this assignment, and I am still surprised by the things I learn, but I was not surprised to know that this was a more egalitarian place than a newspaper.

And, of course, it is a universe removed from those factories of Surat.

Aakar Patel is Executive Director, Amnesty International India. The views expressed here are his own.

- You can read Aakar's earlier columns here.