Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Ehtasham Khan

September 21, 2004

While Islamic scholars in India remain divided on family planning, a section of young Muslims feels a small family is the need of the hour for a better future.

Maulana Syed Kalbe Sadiq, vice-president of the All-India Muslim Personal Law Board, a conglomerate of Muslim groups, sparked the debate by favouring a 'discussion on steps to promoting literacy and family planning among Muslims'.

Islamic scholars from different schools of thought interpret the issue differently. Some call family planning anti-Islamic while the 'liberal' ones stress the necessity to maintain a gap between children.

But a majority of scholars is against the two-child norm. They are against sterilisation too, be it forced or voluntary.

Maulana Rabe Nadwi, AIMPLB president and India's leading Islamic scholar, announced, "There is no place for family planning in Islam."

The popular belief is: God takes care of all those born in this world.

But the idea has few takers among younger Muslims who are part of the emerging middle class among the economically and educationally backward community, which constitutes 13.4 per cent of India's population of more than one billion.

Most of the urban Muslim youth who spoke to rediff.com agreed that "small is beautiful". They all expressed concern about India's growing population. They too were opposed to sterilisation and abortion, but preferred one of the other options – condoms and contraceptives – available for family planning.

Mohammad Adil (27) is the youngest of seven brothers and three sisters. He is working as a salesman in a garment shop in Delhi and will be getting married in January 2005.

Adil, who hails from Bihar's Siwan district, said: "I know the problems of a large family. I have been in one."

All his brothers and sisters are married and have established their businesses, but Adil is still struggling in his career. A graduate in Urdu literature from Aligarh Muslim University, he plans to start his own business in Delhi.

His elder brothers started working after passing out from school, but they ensured that Adil was sent to the AMU for higher studies. But Adil said he was unable to do well in college because he could not get quality education in school.

"All my brothers studied in a government school. I paid Rs 30 as my annual fee in school. I wish my parents had sent me to a convent school. I would have done well in my higher studies and got a better career. But my parents could not afford that."

A strong supporter of family planning, he said, "I will have just one or two children. I have no right to produce children if I cannot give them good education and good food. I don't want to get into a religious debate."

Adil's father was of the view that if each of his sons earned even Rs 2,000 a month, then the family would earn Rs 14,000 a month. This, he felt, was enough to support the family in a small town like Siwan.

But Adil, obviously, does not agree. "That is ridiculous," he said. "You cannot grow. There will be no development if one thinks like that."

Faizanul Haque (29), an executive in a private bank in Delhi, has a good understanding of Islam. The eldest of four brothers and three sisters, he studied in a seminary for five years before joining an Urdu-medium school in Darbhanga district of Bihar. He holds a post-graduate degree in Web designing.

A bachelor, Haque is strictly against sterilisation, but said he would stop at three children. "Sterilisation is unnatural," he argued. "But I will definitely practise family planning. It is difficult to afford a large family these days. Education is becoming expensive and jobs are shrinking. It is my responsibility to give a better future to my children."

He favours a more modern interpretation of Islam taking into view the newer problems and challenges facing the community in the 21st century.

"The problem is that there is no Islamic scholar today who can guide us and explain the relevance of the basic principles of Islam in the kind of life and society we are living in," he pointed out. "There are numerous problems and we don't know how to deal with them without compromising with the tenets of Islam."

Mumbai-based media professional Isteyaq Ahmad (28) said, "I will have one child, but will raise him or her in the best possible way instead of struggling with ten children." He favours greater awareness among Muslims on this issue.

Ahmad calls his method of family planning the 'Islamic way'. He prefers to have sex only during the 'safe' period, when conception is unlikely. "I am not enamoured of sterilization," he said. "It is risky."

Shagufta Shaheen (29) works with a shipping company in Mumbai. She got married in July 2004. Having an understanding husband, she plans to wait for another year before bearing their first child. Then she will wait for at least three years before going in for their second child.

Shaheen is not career-minded. "I want to have a maximum of three children," she said. "I cannot afford more. There is no pressure from my family. It is my personal choice.

"I am not one of those who want to keep their children in royal splendour, but I want to give them a decent life."

Shaheen does not think family planning is anti-Islam. "I have read somewhere that there are several ways of family planning in Islam," she said.

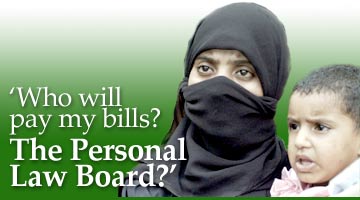

Adil Jamal (35) is creative director of a Dubai-based ad agency called Kromosome. He had just one word to describe the AIMPLB's view: 'mediæval'.

The native of Aligarh town in Uttar Pradesh is getting married in December. "Family planning is very pertinent," he insisted. "The cost of living is going up. Who will pay my bills? The Personal Law Board?"

Jamal said, "Islam is my way of life, but family planning is the reality. I will surely opt for it.

"God has given me sense. We tend to follow the teachings of Koran selectively, like to justify marrying four women and having several children. But Islam is bigger than that," he says.

Shahida Kidwai, technical writer with a multinational firm in Gurgaon on the outskirts of Delhi, is getting married in February 2005. She wants to have just two children.

"For me, it is a matter of convenience, not economics," said Kidwai, who hails from Lucknow. "I can afford to have more kids financially, but two are easier to handle."

Opposed to sterilisation, she said, "I want to keep myself biologically fit for procreation. God forbid, if something were to happen to my two children in the future, then what?"

But most of those who spoke to rediff.com felt uneasy about discussing the issue from the religious perspective. Ahmad was among those who were more forthcoming. When told that god would ensure food and resources for everybody on earth, he retorted, "If that were the case, we would not have found so many beggars and unattended kids lying on the roads. Procreation should be a mutual decision between husbands and wives."

Mohammad Sajjad, who teaches history in the AMU, said the problem of population growth should be seen in the context of the socio-economic and educational status of the people, not along religious lines.

"Population growth is decreasing in the south Indian states where people are more educated, whereas in north India, people cutting across religious lines have more than two children," said Sajjad, who has been studying minority politics in the North.

"A case study in my university, where a majority of teaching and non-teaching staff are Muslims, will make this obvious. Professors of AMU have one or two children while grade IV employees have more than two."

(Some names have been changed on request.)

Photograph: RAVEENDRAN/AFP/Getty Images