S Kalyana Ramanathan walks around the affected parts of London, a fortnight after it was burned by the riots.

There is an unspoken pride Londoners share about the city -- the historic buildings, the Royal family, the English summer, the unparalleled public transport and, above all, the people.

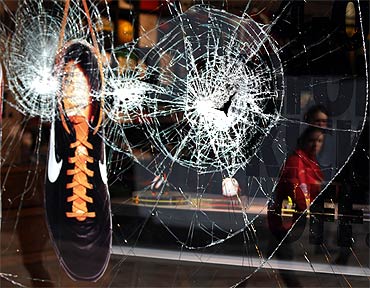

The breadth of ethnic diversity in London is unmatched in the world. It was this pride that took a severe beating on August 6 when a group of rioters, with no stated political agenda, took to the streets in Tottenham in the north of London.

For the next four days, all hell broke loose in the city as well as other parts of England like Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol and Liverpool.

..

A fortnight later, there is little consensus on the reason of the riots, though there is no debate about their origin. Two days before the riots started, 29-year Mark Duggan was shot dead by the police during a gunfire exchange at Ferry Lane in Tottenham.

Initial reports suggested that Duggan was a local gang member and the operation that took him down was a part of the police's attempts to curb gun crimes among Carribbean-African communities.

Duggan's family has denied his involvement in any gang activity. Two days after his death, his family and supporters marched towards the Tottenham police station. The bare facts of the case end here. An hour or so later the protests had turned ugly and spread like wildfire across London.

The police clearly underestimated the force of the riots and was caught unawares in several parts of London. The police's attempts to exert law and order were like a boat with dozens of leaks and only 10 fingers to plug them.

It was three days into the riot when the full force of the police was felt in the streets of London. From 3,000 beat cops, their numbers shot up to 16,000.

Several thousand had to be brought into London from other parts of UK, many pulled out of their holiday and training.

Amidst the confusion the policemen were sure about only two things: The riots always started after sunset and were spreading using social media like Facebook.

Several kids barely in their teens were seen hooded and carrying expensive electronic goods, sportswear and bottles of alcohol out of high-street shops.

Judy Morris, who works at charity Age Concern in Croydon in South London, says her friend's daughter was invited by one of her friends via Facebook.

The message simply said, "Do you want to join the riots?" Facebook and Twitter came under attack and so did text messaging services that were used by rioters to co-ordinate the attacks.

Temporary suspension of rationality led to some demanding that the social media be controlled by the government until the riots blow over. Even the charity offices and funeral parlours were not spared when rioters took to the main roads of Croydon.

"It was mindless vandalism. What could they possibly expect to find in a charity office or a funeral parlour?" says Morris, visibly perturbed.

She, along with her colleagues, has been working for more than a week trying to fix her tiny office where wooden planks now cover what used to be glass panes.

Just a few yards away from this spot is the most visible scar of the recent riots. A half-burnt two-storey residential complex called Royal Mansion.

The 20 families living within the 12 properties have lost everything they had. When attackers torched this building late in the evening of August 8, the residents had to run for their lives, some holding on only to their passport.

A south-Indian family of four, who lived in this building, is now not just homeless but has lost everything it had saved over the last seven years. Subramaniam and wife Priya along with their two sons have now relocated to a place in the neighbourhood with help from the local council.

A church is helping them with food and clothing. The Subramaniams say that theirs being an inter-community marriage, their families back home in India have already abandoned them.

Subramaniam says he is still puzzled by the sweet irony of a Hindu-Muslim couple helped by a local Christian community so many thousand miles away from home.

The politically correct media in Britain is yet to spell out what might be closer to the truth. The riots started with the predominant support of black hoodies.

It also remains a fact that several others without any skin-colour bias joined in soon. Vivian, a black volunteer at a Croydon church, does not like the mention of the colour of the riots.

"This is the first time I am hearing anything like this. This (the riots) has nothing to do with race," she says. Her white co-worker Naomi George agrees with her.

Nicola Davies, health psychology consultant and chief executive of Health Psychology Consultancy based in Clifton, Bedfordshire, says, "The riots were triggered by an ethnic issue, but whether ethnic diversity had a role to play in recent events is a controversial matter. Nevertheless, the looting behaviour would suggest that the riots were more the result of socio-economic disadvantage than ethnic diversity. London faces social inequalities that might have contributed to this looting behaviour."

The social order has indeed changed in London in recent years. Poor people from countries like Somalia are the new occupants of the lower stratum. For example, Southall, once a stronghold of Indian migrants, is now populated 10 per cent by Somalians.

Those Indians who could afford it have moved to the more prosperous neighbourhoods.

Jack, who plies his cab from the Tottenham Hale train station, has a somewhat different take. "You know what I am going to say. It's so black and white. Every other black kid between the age of 16 and 25 is jobless. But then one (community) looks at the other as the problem," he says.

This 54-year-old cabbie sees the problem as something bigger and worse than simple race-specific economic backwardness.

"I used to come from the East side where everyone used to know everyone. That kind of communal bond is all gone now. London is still a good city, but not great anymore."

Jack's apart, there are several dimensions to this apparent social upheaval. While some commentators have dismissed the riots as some inexplicable herd mentality that saw even "Oxford-educated" kids joining the riots, many suspect this to be a symptom of a more deep rooted socio-economic problem.

Morris of Age Concern rubbishes any idea of economic backwardness being the cause, "They (rioters) had Blackberry, which I can't afford. What poverty? I think it's more to do with dysfunctional families."

Davies says technically everyone is susceptible to participate in mob attacks. But recent research has shown that adolescents who lack a stable family can gain a sense of identity when part of a group, and people are more likely to take part in looting during times of hardship and particularly emotional events such as football matches.

Numbers suggest the second factor could be at work in the recent riots. Data provided by the Office for National Statistics says the unemployment rate for the three months to June 2011 was 7.9 per cent of the economically active population, up 0.1 on the quarter; the number of unemployed people increased by 38,000 over the quarter to reach 2.49 million; and the number of people unemployed for up to six months increased by 66,000 over the quarter to 1.23 million.

This is the largest quarterly increase in this series since the three months to June 2009. ONS further says there were 1.56 million people claiming Jobseeker's Allowance in July 2011, up 37,100 on June.

The family stability quotient does not pan out equally convincing if one is willing to look at divorce rates as sign of family stability. ONS says that in 2009 the divorce rate in England and Wales decreased by 6.3 per cent to 10.5 divorcing people per thousand married population, compared with 11.2 in 2008. The 2009 divorce rate is also the lowest since 1977.

The riots also brought out the best in the people. South Asians set their religious differences aside and gathered to save their places of worship in Southall.

The much reviled social media brought together the mop and broom brigade who worked overtime to clean up London. Less than 48 hours after the riots had peaked, an operation tagged "riotcleanup" by one Dan Thompson had become the hottest topic on Twitter.

Similar initiative on Facebook, too, managed to get common folks on to the streets. People on their way to work were picking stuff off the streets.

Some groups also took to the streets with brooms to show the good side of London. Thompson, from Worthing in West Sussex, who used the social media to help co-ordinate the clean-up told Guardian: "There are now people on the ground all across London. People are saying 'we're Londoners, we're resilient and getting on with it'."

While politicians and intellectuals wrangle over the cause and solution for the riot, the common-man touch to the challenge comes from the bottom of the social pyramid. Jack the cabbie sticks to his prognosis: "It is going to get worse."