'The biggest advantage for India was its seasoned and experienced political leadership who had spent decades struggling against the Raj and had spent years behind bars.'

Not a single prominent leader of the Muslim League spent one day in jail.'

'Gandhiji, Nehru and Sardar Patel were intelligent, shrewd men with their hands on the popular pulse.'

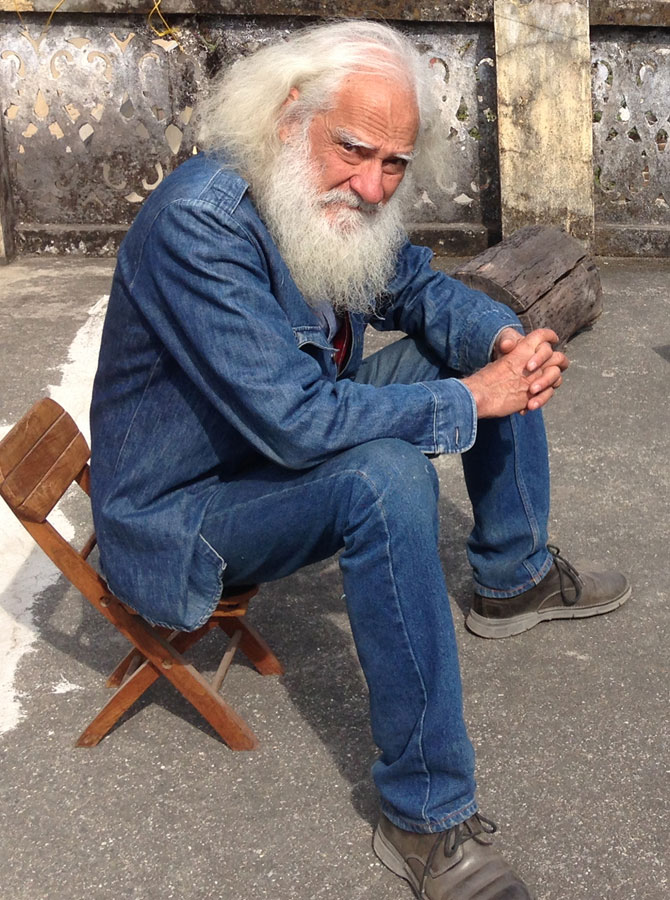

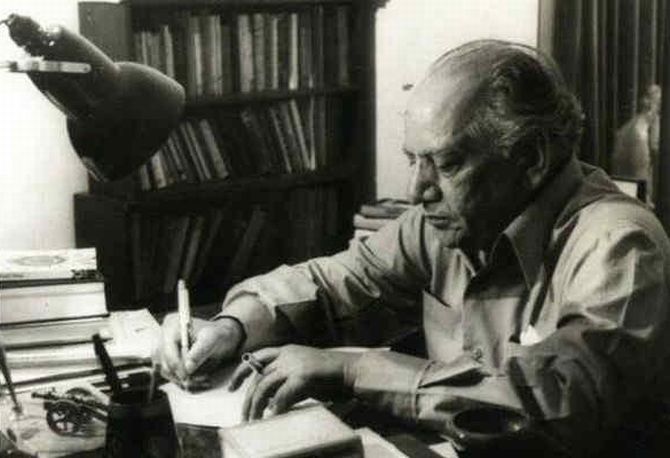

A Marxist but not a card-carrying Communist, the Urdu Poet Laureate Faiz Ahmed Faiz was often perceptibly a bundle of contradictions.

A poet involved in an attempted coup by a curious combination of leftist politicians and a maverick general, Faiz later won the Lenin Peace Prize in the then Soviet Union and has endured the weather-beaten path that poets and their opuses often tread.

Dr Ali Madeeh Hashmi, Faiz's grandson, has published a biography of his grandfather, Love and Revolution -- Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

Dr Hashmi tells Syed Firdaus Ashraf/Rediff.com about the trials and tribulations Faiz endured during his twilight years in Pakistan.

The Communist Party of Pakistan could never establish itself after the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case. Why did the Communists fail so badly?

Because many of their most committed and dedicated cadres were Hindus and Sikhs who left after Partition, so really, there hardly was a Communist Party of Pakistan.

Sajjad Zaheer was sent over from India specifically to try and rebuild the party in Pakistan and he tried his best, but it never really took off.

There were some honourable names who worked hard and in some cases gave their lives to the party's cause (the late Hassan Nasir), but the conditions just weren't there for the party to be able to flourish.

Of course, they were fiercely suppressed by the government, much more so than in India especially after the conspiracy case which actually was more of a conspiracy against the Communist Party.

The Left has always remained splintered and ineffectual in Pakistan. Their heyday was the (Zulfikar Ali) Bhutto government's early years and even then there was a split amongst the Maoists and the followers of the USSR.

Then the East Pakistan debacle (the birth of Bangaldesh) divided the movement further and all the while, they were suppressed and hunted down relentlessly and it continues to this day.

After the Rawalpindi conspiracy, the Pakistan army and civilian government in your opinion could never come to terms with each other. Why was that?

What advantages do you think India had over Pakistan where we had a stable democracy, but not your country?

The biggest advantage for India was its seasoned and experienced political leadership who had spent decades struggling against the Raj and had spent years behind bars, an indication of the British rulers' feelings towards them.

Not a single prominent leader of the Muslim League spent one day in jail which goes to show what their attitude towards the British was.

It helped that Nehru and his compatriots had Socialist leanings (even though they were far from being 'hard' leftists) but at least they were sympathetic to the plight of ordinary people which always ensures some popular support.

The League leaders were feudal lords and, with the exception of people like Mian Iftikharuddin, they were rabidly opposed to democratic and popular aspirations.

Gandhiji, Nehru and Sardar Patel were intelligent, shrewd men with their hands on the popular pulse.

Besides Jinnah who was a brilliant lawyer and tactician, the other League leaders had not put in the hard work and planning of what was to happen after Independence.

There was no blueprint, no framework for how the government of this new country was to be run except for a few speeches of the Quaid-e-Azam (Jinnah).

The reason that the army formally took over in Pakistan in 1958 and has maintained an iron grip ever since is that the politicians were, and are, pretty clueless.

Just look at the history of Pakistan from 1947 to 1957. It was a total circus with governments conspiring against themselves, prime ministers playing musical chairs and ordinary people being crushed under the burden of inflation and poverty.

I saw an interview with (Field Marshal) Sam Manekshaw in which he described how he jokingly threatened Mrs Indira Gandhi during the 1970s with a military takeover and she just brushed him aside.

She knew, and so did he, that a government with some popular support can never be deposed by the army.

But that requires politicians who are intelligent and in tune with the aspirations of ordinary people. You don't have to be geniuses!

People want roti, kapda, makaan (food, shelter and clothing). It's not rocket science.

After his release from jail in 1955, Faiz became less involved with the Communist Party of Pakistan, unlike Hassan Nasir who gave up his life for the movement.

Was Faiz an armchair Communist?

That's a hard question and I've tried to answer it in the book. No, I think he was very committed to Communism, but he was an intelligent man and he knew that there was no way the government of Pakistan would allow him to carry on his activities.

His imprisonment from 1951 to 1955 had proven that. His family (my grandmother, aunt and mother) had suffered terribly during that time and he made a decision when he came out that he was not going to put them through that again for his, as he put it 'selfish idealism'.

It doesn't mean he renounced his ideology. He could have, and he would have been handsomely rewarded by the Pakistani government, but he chose to concentrate on the arena he liked and knew best: Culture and the arts and he continued his activism in that arena. And by the way, he continued to be hounded for his beliefs and his activities.

He went to jail again briefly in the Ayub Khan military dictatorship, he was followed everywhere when he was in Pakistan, his friends and acquaintances were harassed, he had to flee again when the Zia dictatorship arrived.

I suppose in a way he did dedicate his life to Communism and it was a hard life: No financial security, no fixed home (although that was partly by choice), no titles, no lands, nothing.

In the end, all he left behind was his books and his ideology. And that's the way it should be.

Why did Faiz never think of migrating to India, unlike Sajjad Zaheer, a co-accused in the Rawalpindi case, who did so later?

Because he knew the degree of animosity that existed between the two governments and that, if he did, he would never be able to return to Pakistan.

And ultimately, he was from Sialkot, which is now in Pakistan and he loved Lahore, his adopted city. He travelled so much that I don't think it mattered to him where he actually 'lived'. He was a citizen of the world.

All his life Faiz was trailed by the Pakistani police. How did he get the strength to overcome such surveillance?

I think he understood it as the price that was to be paid for a certain degree of notoriety. He was always careful to separate the 'policy' from the men who were tasked with implementing it.

There are so many stories (I've written some in the book) about how he would invite his CID police watchers into his house for a cup of tea or a meal and when my father or uncle would object, he would say it's alright, its hot, the poor man has been standing outside for hours, let him eat something and rest.

I am still amazed about stories like that which I discovered while writing the book. That kind of generosity of heart, so much love for all humanity, such forgiveness, it truly is inspiring. Most of us can only ever hope to achieve a fraction of that.

Is it true that Faiz said in an interview that India is like mehbooba (lover) for him and Pakistan is like a mankuha (lawfully wedded wife) and therefore he could not settle in India?

Yes. He did say something like that, I think. I don't think I have quoted that in my book because I probably couldn't find a proper reference for it.

Faiz joined the Bhutto government, although many felt that he should not have as Bhutto declared the Ahmadiyas as non-Muslims and he also dismissed the elected government in Balochistan.

Faiz joined the Bhutto government, although many felt that he should not have as Bhutto declared the Ahmadiyas as non-Muslims and he also dismissed the elected government in Balochistan.

Did Faiz regret his decision to join the Bhutto government?

Faiz joined the Bhutto government at the personal request of Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. He did spend some time in Islamabad and it was due to his efforts that the Pakistan National Council of the Arts and the Lok Virsa (Folk Heritage) museum came into being. Both organisations are still running and prospering.

Faiz dissociated himself fairly quickly from the Bhutto government and moved back to Lahore. Though this was not specifically because of the Bhutto government's treatment of the Ahmadiyya issue, but because of a general disenchantment with the way things were being run.

Bhutto sort of lost his way early on and that was a big reason why he was deposed and later executed. I don't think Faiz regretted his decision, but perhaps he may have been sad at another opportunity to improve Pakistan being lost.

During General Zia-ul Haq's regime Faiz did not settle down in Calcutta in self-imposed exile, but went to work in Beirut instead. Why was that?

Because he knew that if he worked or settled in India, it would make life difficult for all of us, his family, in Pakistan; he said as much and that's in the book. He had an offer to become a professor of Urdu at Calcutta University, but did not take it for the same reason.

What makes Faiz's poetry relevant in this age?

This is from the last chapter of the book: One reason for Faiz's enduring popularity is 'his conscious commitment to being a spokesman for ordinary people: Workers and peasants, women and children, all those who have no voice in the oppressive societies of underdeveloped, Third Wworld nations.'

'He made the decision to speak for them, in his own way, early on in his life and, by and large, upheld this commitment. This alone would have been enough to endear him to a large majority of the people in all countries where Urdu poetry is read and appreciated.'

'In Pakistan, India and the subcontinent, where poets are revered just a little less than prophets; it has won him millions of ardent followers.'

'Faiz is gone, but his voice is still with us in his poetry, and so are those things in the world that so rankled and infuriated him: exploitation, injustice, tyranny, oppression.'

When there is no more injustice in the world, no more oppression, perhaps people will forget Faiz but I doubt it.