British-Indian filmmaker Gemma Atwal was born in India, but her mother left her at the hospital, possibly because she was not born a boy. She was then adopted by a wealthy United Kingdom-based Sikh man, who adopted eight Indian kids from Hindu, Muslim, Sikh backgrounds.

When Atwal decided to work on a film project in India, it was natural that she was drawn to the story of Budhia Singh (born in 2002), a young boy from Orissa who was sold by his poor mother for Rs 800 ($16) to Biranchi Das, a judo instructor, who also ran a foster home for young kids in Bhubaneswar, Orissa.

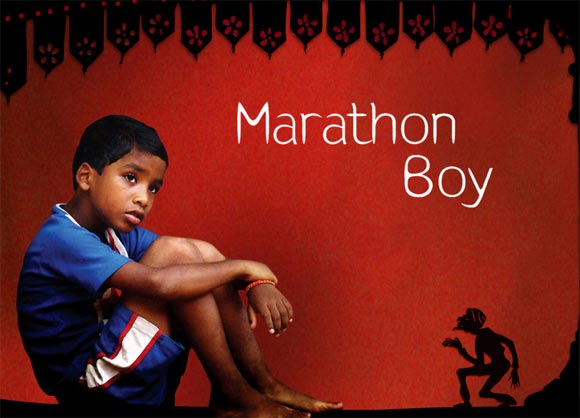

Biranchi saw the running talent in Budhia at the age of three and started training the young kid to run marathons. Atwal's film Marathon Boy explores the complex story about the child, the man who adopted him, and how their relationship played out in a changing India.

Marathon Boy, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in April and recently won the best new director award at the Abu Dhabi film festival, plays on HBO November 3. Atwal spoke to India Abroad about what went into making the film.

Were you drawn to Budhia's story because of your background?

Yes, and also hearing the story of the mother who I identified with. I also identified with Biranchi who gathers a rag-tag bunch of kids. He kind of reminded me of my father a little bit, especially his altruistic spirit. Also I wanted to do a project in India, and I run as well.

Are you a marathon runner?

Yes. (I have run) about a dozen, actually.

Did you shoot all the footage, or was some of it given to you?

When my fellow producer Matt Norman and I started the project, we didn't know much other than this boy with an extraordinary talent and this incredible relationship (Budhia and Biranchi). Initially, we thought we would follow this boy over many years, until he was 17 or 18. So, we started self-funding regular trips to India and would spend three weeks to four months filming... Since we were going back and forth, there were times when we missed a catalyst event. So, we would go back for the reaction to the event. We would sometimes buy Indian archival material, because Indian television was following Budhia all the time. We wanted to make it a present continuous unfolding drama. It has that drama quality to it as well. I didn't want a back story and too many scripted explanatory scenes.

There is a scene when the boy throws up after that a race. Was that your footage?

That was news footage. I always grappled with how much I could interfere in the boy's life and at that moment I could see the anguish on his face, so I had turned off the camera. Normally, when he ran he would be happy.

The reason I am asking, and I am not making a judgment, is because I wanted to know why you made the decisions you made to show some very sensitive footage, which the media in India does all the time. There is no sense of the individual's privacy.

But that is India for you, and especially the media in the country. The power of the media is scary. They are a direct player. We did try to distinguish ourselves from the local media though. We wanted to show how the media became an active player in the story. Biranchi never tried to court us, because he knew that we couldn't influence his fate. He also didn't know where and when the film would be shown.

But he loved attention so he was fine with you and the other cameras? And the kid was fine too?

Yes, and for Budhia it was a mini Truman Show. It wasn't pleasant. He was so manipulated, and he couldn't stop the media frenzy around him.

There are things you chose not to explain. Biranchi has a foster home, but how does he support it? Does he have businesses?

We hinted at some of it. He goes to carpenters' shops, so he makes things and he has roadside small restaurants. He has a little barber shop. He and his brothers run those businesses. Possibly there might be some shady deals, because he is a president of the particular slum area association. He also regularly sorts out all the petty crimes and disputes between the slum dwellers. And I realized that these boys at the judo club had quite a reputation that they would go out and sort out disputes. But Biranchi wasn't a rich man.

It is also fascinating when you are a celebrity, the power of the media is huge and that is one of the themes of the film. Also, what is truth, objective versus subjective truths?

Where did you sit in the element of truth? You present us with a lot of facts, but I also kept thinking that if I were in your shoes, what would I believe and not believe in? There are some rather ugly stories that are part of this boy's life.

I wanted to objectively observe things, while I was grappling to understand what was the truth? And while this was going on, none of us knew whether Biranchi was making a lot of money (as he is accused in the film). There were claims and counter claims, continuously going on. It became an outright war between the state government and Biranchi. I had a lot of private conversations, but ultimately I decided that we should just document how both sides feel... I didn't want this story to be a neatly-packaged one. There were themes of who has the right to define abuse.

What is the vested interest of the state government in Budhia's case when there are hundreds of thousands of other kids on their doorstep living in great social misery?

I see the story from the points of the view of the two worlds. I didn't want to give it a feel that it was seen from the prism of a Western perspective and all the rights and the freedoms I have. It could have been so easily a story of child exploitation. But I wanted to set it in the Indian context and give it an Indian perspective. It's the story of a guru and his disciple. It is a classic underdog story, a kid from the slums who breaks the class divide and travels the superhighway as many do, and Biranchi who is the anti-hero, the deeply-flawed lead character.

Biranchi must have been getting some satisfaction from what he does?

Absolutely. It's philanthropy vs opportunity; it's saint versus Svengali. He reminds me of Fagin in Oliver Twist — he teaches them petty crimes in exchange for a roof over your head. Biranchi built this judo training center over stolen land taken from the government... He associated himself with really powerful people in the Opposition Congress party and he knew that the government wouldn't take his land.

Have they seen the film in Bhubaneswar?

They haven't seen the film yet. I would like to show it to Budhia at some point. I am not quite sure how he has processed the events in his life. He's in a good place right now, with his mother and he goes to a school. He's now shielded from the media. He's not being forced to run these long distances, which is great.

What did you make of the mother?

I really felt for her; she was a pawn in so many people's lives. She just wanted a house. But she was equally manipulated by the people behind the scenes.

You recall the film Born Into Brothels? Once it was made there were all these allegations about people from the West exploiting the poor in India. Also, all that happened after Slumdog Millionaire to some of the actors. Did you ever think you would be looked upon from that perspective?

I was really conscious about that. Even at the Tribeca Film Festival, there was a thought about bringing Budhia over. But I was adamant about that. I made sure that won't happen, because I don't see anything in it for him. For the film, I was very keen that it does not become a how-do-we-save-this-boy story? To me, it is also a story about the political and social dimensions of a modernizing India: Poverty, slums, police corruption, crime, media — all those things that are more interesting than just my take on the boy's life.

You have established two foundations. Can you talk about them?

We announced the trust funds at the Tribeca Film Festival. One is a fund for Budhia to help him through his childhood to adulthood and the other for the rest of the kids at the judo center. We set up trust funds through our Web site — www.marathonboymovie.com

What did you learn from making this film?

With this film you have to drop all preconceived notions. Filming in India, you have to discard all the sense of what you take with you and brace yourself for surprises. People aren't black and white and I love films about anti-heroes that show the full complexities of the character. Then there is the story about the child: Who has the right to keep him — the mother who sells him off or the man who cares for the boy?