"No, we did not get sick!"

...an American couple's honeymoon encounter in wonderful India

TJ Mark

Dear family and friends, Dear family and friends,

Slobhan and I have returned safely from our journey (honeymoon?)

to India! I apologize in advance for the use of a form letter,

but we have so many stories we wish to share with so many people

that it seems excusable.

Many people have questioned us: Why did we choose to go to this destination during

the only time in one's married life intended solely for marital bliss? We have my brother, James,

who has been living in Bombay for nearly three years to blame

for that.

We also have James to thank for researching, organizing

and guiding an unforgettable experience that took us from the

vast Thar Desert on the border of Pakistan, through India's spiritual

heart on the banks of the river Ganges, to the foothills of Mount

Kanchendzonga within the untouched antiquity of Sikkim. Here are

some of our observations and experiences:

The answer to everyone's first question is: "No, we did not

get sick." India's reputation for making food that works like

"liquid plumber" obscures just how tasty the food is.

All the hip, expensive, organically grown vegetables that are

so coveted here in Bezerk-eley are the standard fare in Indian

markets and restaurants. Even though a raw salad might be a dangerous

selection, the veggies are excellent, once cooked.

India also has an abundance of intensely hot spices grown, I believe,

somewhere below the earth's core. We worried more about the cells

native to our mouths than any intruding parasites.

Granted, I

did not take many extreme culinary chances with local food -- like

eating at the equivalent of a roadside hot-dog stand -- sticking

mostly with the fare offered at the western-style hotels and more reputable

looking restaurants.

That, of course included a mandatory pilgrimage

to the newly opened McDonald's in Delhi. As the preponderance

of cows (held sacred by the mostly Hindu population of India)

in the streets and alleys of any city will attest to, there are

no holy bovines on the menu. Instead, we had to suffice with the

Big Mac's distant cousin, the Maharajah Mac -- two all-mutton patties

on a sesame seed bun.

As this was Slobhan's first trip overseas, I think she is now

prepared to travel anywhere in the world without blinking. India =

culture shock. As this was Slobhan's first trip overseas, I think she is now

prepared to travel anywhere in the world without blinking. India =

culture shock.

From our first experience of stepping out of the protected enclave

of the international airport into a churning mass of people hawking

services and handicrafts, to the bustling city streets, whose rich

cultural and architectural history stands battered by yearly monsoons

and a perennial, choking haze of exhaust and dust, there is not

a single sense, in five, that escapes taxation by such an extreme

environment.

To see India in a microcosm, you need only to drive

down the crowded streets of any town or city. There is a form of

"vehicular Darwinism" that reflects how survival is

an individual, not collective, pursuit. The rules of the road

are really quite simple compared to the vehicular codes so heavily

enforced in the States: Do whatever necessary to get from point

A to point B without, if possible, hitting anything.

This is complicated

only by the variety of unregulated activities that proliferate

on every street. Besides the usual trucks, taxis and cars, there

are three-wheeled scooters with covered carriages, called autorickshaws,

that wind erratically between the bicycles, people-drawn bullock

carts, vegetable stands, beggars, motorcycles, pedestrians and,

yes, even cows that share the crowded byways. The direction of

traffic is often determined by which side of the street has more

space and it is not unusual for it to commandeer a populous dirt sidewalk,

if traffic has slowed or stalled. In India, pedestrians reserve

the right to get out of the way!

Communication also presents some curious difficulties. Even though

the predominant language is Hindi, English is spoken to some extent

by almost everyone. The humorous Indian accent made famous by

the snack shop clerk in The Simpsons apparently comes from the

south. The Northerners had a much milder accent.

What was far

more difficult to comprehend than what was said, was how it would

be understood and then, invariably, translated, to incorporate

some hidden agenda. Many times, you order one dish and get another -- only

to find they didn't have it in the first place. Whether it was

considered rude or just too much trouble to tell you, is hard to

figure.

A taxi driver in Agra drove well

over five kilometers before confessing he did not know where he was

taking us -- despite the fact that we had agreed to pay him a fixed

fee for the trip. Another taxi driver in Varanasi, when asked

to take us to the famous Old Market, recommended another

shopping district that was less "touristy" (at which

he would probably given a commission for bringing us) After insisting

that we wanted to go to the Gora Market (means white

in Hindi), he took us to the other area anyway, protesting upon

our refusal to pay: "Ooh, you meant the tourist market".

Such encounters were commonplace in a culture where haggling

is the norm and tourists stand out as particularly fatty prey.

Without the weathered guidance of James, Slobhan and I would have

collapsed under the struggle that even the smallest purchase would

require.

Communication was often undermined by a general lack of accountability

as well. You might as well be talking to a wall if nobody feels

that they are responsible for your predicament. Under these circumstances,

customer service was always the first victim. Planes honour no

schedule. Trains are invariably late. Taxis charge indiscriminate

rates. And hotels often deny your confirmed lodgings in hopes

of changing your fixed rate to a more expensive one. Even some

"officials" are unreliable at best -- subject to laziness or

bribes -- as we discovered one eventual evening at the Mughalsarai

Station, just outside the sacred city of Varanasi.

We arrived

at the station several hours before our estimated departure at

11:45 pm for the overnight train to Calcutta. As is the case with

most stations, it was dirty, poorly lit and inadequately marked

with signs.

To our relief, only ticketed passengers could make

it out to the platform. So instead of fending off peddlers, we

could focus on the far more interesting pastime of counting and

sizing the rats on the tracks below. Being the only goras

in the station and, of course, Slobhan being a blond, we attracted

the usual intense though harmless Indian stares. It was

not uncommon for someone to stand ten feet away and just watch

us for five or ten minutes without interruption or intent.

When our train finally arrived one hour late, we were anxiously

anticipating the confirmed sleeping compartments of our second

class coach. As we threw our bags upon the train, the conductor

surprisingly informed us that the coach was full and we could

not board.

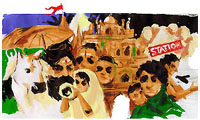

Sketches by Dominic Xavier

|