As India and China continue to face off across the Himalayas six decades later, the echoes of that earlier conflict remain unmistakable.

The core of China's sensitivity lies not in maps or mountain passes, but in its perception of sovereignty over Tibet, points out Dr Kumar.

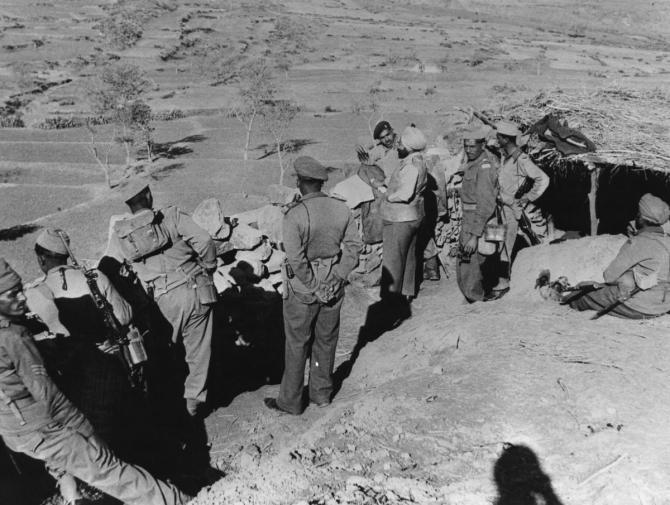

On October 20, 1962, Chinese troops launched a full-scale offensive across the entire Himalayan frontier, from Ladakh to the North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh).

The brief conflict that followed ended with a unilateral Chinese ceasefire on November 20, 1962, leaving India strategically vulnerable.

Much has been written about the causes of the conflict: the disputed boundary, the personality clash between Mao Zedong and Jawaharlal Nehru, and India's so-called 'forward policy'.

However, emerging archival research and declassified Cold War records suggest these explanations only scratch the surface.

At its heart, the 1962 War was less about disputed borders and more about Tibet, reflecting Beijing's determination to respond to what it perceived as India's interference in its internal affairs.

The origins of the Sino-Indian conflict can be traced to the Tibetan unrest that began in 1956 and culminated in the Lhasa uprising of March 1959 against Communist rule.

What initially appeared as a local protest soon escalated into a widespread rebellion that threatened China's authority over the plateau.

On March 20, 1959, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) was ordered to suppress the revolt with force.

By the end of the month, the Dalai Lama had fled Lhasa, and on March 31, he crossed into India seeking asylum.

Prime Minister Nehru's decision to offer him refuge, in keeping with India's humanitarian ethos and deep cultural ties with Tibet was viewed in Beijing as an act of grave provocation.

For China, the Lhasa uprising was more than a domestic crisis. It exposed the limits of Communist control over Tibet, cost tens of thousands of PLA casualties, and opened the region to covert Western interference.

Between 1957 and 1961, the CIA had trained hundreds of Khampa rebels in the United States and bases in Southeast Asia, supplying them with arms and equipment through airdrops into Tibet.

By the end of 1961, over 250 tons of weapons, ammunition, radios, and medical supplies had been delivered to insurgents resisting Chinese occupation.

These aerial operations were launched primarily from bases in East Pakistan, with New Delhi neither aware nor in a position to prevent them.

However, to China, it seemed logical that such a massive rebellion could not have been sustained without India's tacit support or use of its territory.

As a result, Beijing came to view India as complicit in what it called an 'imperialist conspiracy' to dismember China.

Deng Xiaoping, a rising figure in the Chinese Communist party, accused Nehru of being 'responsible for the rebellion' and warned that China would 'settle accounts' with India in due course.

For Mao Zedong, who saw Tibet as a vital buffer against Western encirclement, India's role in sheltering the Dalai Lama symbolised a broader challenge to Chinese sovereignty.

While Beijing and New Delhi exchanged diplomatic protests, the CIA expanded its covert operations.

In April 1959, then US dresident Dwight Eisenhower authorised increased aid to Tibetan rebels, including aerial supply missions and intelligence-gathering U-2 flights over Chinese territory.

Tibet became a Cold War battleground. Washington saw the rebellion as an opportunity to destabilise China and drive a wedge between India and China by fuelling distrust over Tibet.

Eisenhower reportedly told then CIA director Allen Dulles that the uprising would 'help Nehru recognise the real danger from Communist China'.

These covert efforts, as anticipated by the CIA, intensified Chinese suspicions of India.

By late 1961, CIA operations had shifted to Mustang in northern Nepal, where several hundred Tibetan fighters were trained and supplied.

The campaign tied down large Chinese forces in Tibet, forced repeated reinforcements, and hardened Beijing's resolve to silence external interference once and for all.

At its height, the rebellion involved nearly 14,000 Tibetan guerrillas. Chinese military reports, though censored, indicated staggering casualties among PLA troops and civilians.

One Western estimate placed total Chinese losses in Tibet between 1956 and 1961 at nearly 80,000.

The political cost was even higher. For Mao, the rebellion represented a humiliation inflicted by imperialist forces using India as a base.

From this point onward, India was no longer seen as a neutral Asian neighbour but as a proxy of the West.

In April 1959, barely weeks after the Dalai Lama's flight, Mao convened an enlarged meeting of the Chinese Communist party's politburo in Beijing.

The discussion marked a turning point in China's foreign policy. Mao declared that China must launch a 'counter-offensive against India's anti-China activities', openly identifying Nehru as an ideological adversary.

He ordered the Chinese propaganda apparatus to directly attack Nehru and the Indian government for 'interfering in China's internal affairs' and 'colluding with imperialists'.

A few days later, the People's Daily newspaper published a lengthy editorial titled The Revolution in Tibet and Nehru's Philosophy, personally edited by Mao.

It accused India of betraying Asian solidarity, supporting rebellion in Tibet, and harbouring ambitions over Chinese territory.

The article rejected Nehru's claim of neutrality, describing India's asylum to the Dalai Lama as proof of intervention.

It was clear that Beijing had begun to link its Tibetan troubles directly with its border problem with India.

By mid-1959, these political hostilities began to manifest on the ground.

On August 25, Chinese troops clashed with Indian forces at Longju in the North-East Frontier Agency, the first violent confrontation between the two armies.

A few weeks earlier, another skirmish had occurred at Khinzemane.

The timing was no coincidence. Mao's shift from diplomatic protest to armed confrontation mirrored his conviction that India, not local resistance, was the source of unrest in Tibet.

The Longju incident triggered an anxious response in New Delhi. Nehru sought Soviet intervention to restrain Beijing.

However, Moscow, attempting to balance relations between the two Asian powers, issued a neutral statement through its State news agency TASS on September 9, 1959.

The Soviets' fence-sitting angered Mao, who saw it as a betrayal of Communist solidarity, and publicly exposed the widening Sino-Soviet rift.

The rift was on full display on October 2, 1959, when then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev met Mao in Beijing.

Fresh from his talks with Eisenhower, Khrushchev cautioned Mao against escalating tensions with India.

He described Nehru as the 'best possible leader India could have' and advised restraint.

Mao reacted sharply. 'This is Nehru's fault,' he insisted.

'The Hindus act in Tibet as if it belongs to them. In the question of Tibet, we should crush him.'

The exchange quickly turned into a heated argument. While the Soviets maintained that China was to blame for the violence at Longju and for mismanaging Tibet, Mao insisted that India had provoked the crisis by supporting "reactionaries" in Lhasa.

To mollify the Soviets, Mao later remarked that the McMahon Line would not be repudiated and that the border issue would be resolved peacefully, but his underlying message was unmistakable.

For China, the border dispute was secondary; the real issue was Tibet, where Beijing held India responsible for every setback it had suffered since 1956.

Between 1959 and 1962, the pattern of Chinese conduct followed Mao's long-held method of strategic patience.

While engaging in talks with India, China strengthened its military infrastructure in Tibet, built roads up to the disputed border, and maintained a steady campaign of propaganda accusing India of expansionism.

Meanwhile, the Dalai Lama's government-in-exile in India became an enduring reminder of Nehru's defiance.

India's 'forward policy', launched in 1961 in response to China's ever-increasing encroachments and their definition of the Line of Actual Control, was intended merely to show presence and reassert territorial claims.

But to Mao, it appeared as an opportunity. When Chinese patrols reported increasing Indian outposts in the Aksai Chin, Beijing saw an opening.

As Mao had told Khrushchev three years earlier with respect to their operations in Tibet, 'We could not launch an offensive without a pretext. And this time, we had a good excuse.'

Similarly, in 1962, a combination of geopolitical conditions and continued border tensions gave China the pretext it needed.

In the decades since, Indian and Western scholarship has tended to focus on the border issue and the failures of diplomacy.

The narrative of a naive India misreading Chinese intentions and a forward policy provoking retaliation remains influential.

However, declassified Chinese and American records now allow a more nuanced understanding.

They reveal that Tibet, not the boundary, lies at the heart of China's hostility.

The CIA's covert war, the PLA's losses in Tibet, the asylum to the Dalai Lama, the perceived support by India to the Tibetan rebellion, and Mao's personal sense of humiliation combined to make confrontation with India inevitable.

The 1962 War, therefore, cannot be understood in isolation from the Tibetan crisis. It was less about territory than about ideology, legitimacy, and control.

For Mao, striking India was a way to reassert authority over Tibet, demonstrate China's resolve to the Soviets, and warn the West against meddling in its periphery.

As India and China continue to face off across the Himalayas six decades later, the echoes of that earlier conflict remain unmistakable.

The core of China's sensitivity lies not in maps or mountain passes, but in its perception of sovereignty over Tibet.

Understanding 1962 through this lens does not absolve India of strategic errors; it restores the conflict to its proper context, as the culmination of Beijing's quest to secure Tibet and silence what it saw as foreign interference.

The conflict, at its heart, was born out of China's insecurity in Tibet.

The boundary issue simply became a tool that China continues to employ to pursue broader strategic objectives beyond Tibet, and it is unlikely to give it up any time soon.

EARLIER IN THE SERIES: How India Got The MiG-21 63 Years Ago

Dr Kumar is a Research Scholar who has extensively researched the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict and the Cold War dynamics.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff