On the day of Ajmal Kasab's trial verdict, rediff.com's Nithya Ramani and Abhishek Mande visit the ill-fated hospital and discover how staff members are coming to terms with 26/11 attacks.

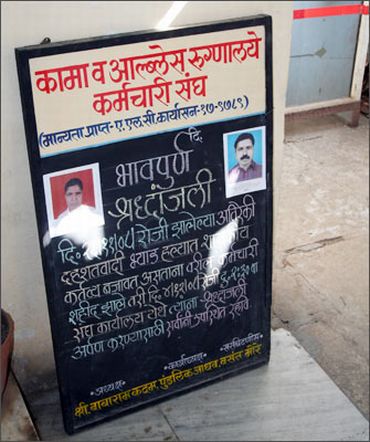

The staff at the Cama and Albless Hospital in Mumbai are still trying to come to terms with the carnage they witnessed on November 26, 2008. One of the most prominent hospitals for women and children, the hospital's thick stone walls resounded with gunshots that continue to haunt some.

Dr Archana Garud abruptly walks away when she realises that we are journalists looking for a story on the day of Ajmal Kasab's verdict. The supervisor, who is to permit us inside the hospital, say almost in hushed tones, "She was there that day."

'That day' is how everyone refers to 26/11 at Cama. No one takes Kasab's name either. He's simply called 'that man', more out of hatred than fear. These are just some of the ways in which the staff members at Cama are coming to terms with the tragedy. ...

Today, he looks forward to returning to work. He has his friends here and this is the only life he has known. Pawar asks us what we do and wishes he'd studied more, "I wouldn't be a liftman. I'd probably be someone like you." Behind him, the bullet-ridden lift is temporarily closed.

Vilas Ughade hesitates when he tells us that he hasn't cleared his tenth grade. The 30-year-old's father, Baban, was a security guard who fell to the terrorists' bullets.

Ughade got a job at the hospital after his father's death. However, he is a ward boy and not a guard like his father. He says, "I was a delivery boy at a private company. That night I came home and was watching it on television. I called up (the switchboard) to enquire about my father. One of my friends who was on duty at the time told me that my father had been killed."

"I didn't know how to break the news to the family so I didn't. The whole night everyone at home was awake, watching the news, hoping that my father would survive. I was the only one who knew the truth. At four in the morning, the police knocked on our door. They asked my older brother, Vitthal to accompany them to the hospital. That's where he first saw our father, dead."

Ughade speaks plainly and betrays little or no emotion. He poses for photographs and even directs us to his house where his family lives. On his opinion about the verdict, Ughade simply shrugs and says: "He should be hanged. But it all depends (on what the judge has to say)."

He then turns around and strolls back to his ward. There is work to be done.

Back at his tiny two-room apartment, a television blares. Lakshmi, his sister-in-law is the only member at home. In the extended part of the house, three young children sleep peacefully. Lakshmi tells us that her husband and mother-in-law have gone to Sion where the government-allotted apartment awaits them.

"We move in a month," she says.

Hailing from Anand in Gujarat, the Waghelas thought that their home -- a chawl near Cama and Albless Hospital -- in Mumbai was far from danger with the Azad Maidan Police Station nearby. Little did they know that the night of November 26 would shake their world and break their trust on anyone they now see or meet.

Thakur Waghela, a sweeper with GT Hospital, was shot dead at his home on the dreaded night.

Karuna Waghela, Thakur's wife has now been given a job at GT Hospital and the family has been promised compensation for their children's education. Karuna is beginning to get used to the media attention. The moment any news related to the attack surfaces, the media tries to reach out to her.

The night is fresh in her mind. Tears roll down as she recollecting the horror. "My husband was watching a match on TV and having dinner when he heard gunshots from VT station. He didn't know what was going on. My youngest son, Niraj, was with him at home when heard a loud knock on the door asking for water. Since we live near the hospital and there have been many cases when pregnant women in labour deliver at home and their relatives come asking for water.

Thinking it was one for those scenarios, my husband opened the door to the two terrorists. He obliged them with water and they pointed their gun at him. Niraj silently hid himself in the bathroom. Despite requesting them not to shoot, they fired on my husband and ran away. Niraj then came out and saw his father in a pool of blood."

Though she seems to have dealt with the fact that her husband is no more, Niraj (now six) cries himself to sleep every night because the image of his father lying dead in front of him hasn't erased from his memory. Waghela fears it never will.

Though the government has decided to give a compensatory amount for the family of the victims of the terror attacks, Waghela says the money would be for their children.

She claims that they haven't received a single penny from the government nor has the school received any money for their children's education.

While she points out that education for up to two children is free in the state, she hopes that the privilege is extended to her third child too.

When her husband was alive, Waghela lived in the allotted chawl near the hospital. Since the government has allotted houses for the victims, she has shifted to Sion with her children and her parents.

Shinde's daughter Ashwini studies in the seventh grade at a school in Sion and her son is studying in the Elphinstone College in downtown Mumbai. She adds that their daughter, who saw her father die before her eyes, has resolved to become a doctor. "She wants to help those like her father."

A little tragically, the other thing that binds the two families is their hatred for the man who killed the two men. Ashwini, Shinde tells us, wants him to be shot before he is hung. Niraj on the other hand is convinced his father will return once Kasab hangs.