Home > Cricket > World Cup 2003 > Columns > Sunaad Raghuram

The Ramavilasa Road racehorse

February 12, 2003

Srinath's 300 wicketsThe royal patronage of the legendary Wodeyar dynasty evolved the city of Mysore into one of exquisite character. It is a city where the clock ticks ever so slowly, putting on show, on the dial of life, the kaleidoscopic images of royal personages who walked the city's soil for long years in glorious splendour; the broad tree-lined, bougainvillea-smothered boulevards and the grandeur-filled edifices that dot the city, a testimony to their scope and vision.

It's a city where the air is still heavy with the dignified aura of royalty when, in the years long past, the Maharaja presided over myriad esoteric pursuits ranging from the fine arts to wrestling; a place like none other, where the rich ambrosia of heady culture permeated the very existence of its people.

The Mysorean is a gentle, soft-spoken, easy-going kind of man for whom the din and tumult of a Bangalore or Mumbai is anathema; a kind of culture shock which leaves him dumb founded. Not to him the mindlessness of heavy traffic, not to him the frenzied pace of business, not to him the rush hours of life where clambering on to a bus or a train defines the difference between success and failure.

The Mysorean is a gentle, soft-spoken, easy-going kind of man for whom the din and tumult of a Bangalore or Mumbai is anathema; a kind of culture shock which leaves him dumb founded. Not to him the mindlessness of heavy traffic, not to him the frenzied pace of business, not to him the rush hours of life where clambering on to a bus or a train defines the difference between success and failure.

To the Mysorean, life was almost always meant to be an unhurried, relaxed, quiet and elaborate repast. And even to this day, it is largely so.

Not too far from the wondrous palace of the Wodeyars, with its shining red domes, in the middle of the old part of Mysore is the Ramavilasa Road. Narrow, with mostly ancient houses on either side, wedged closely together, this road has etched itself on the city's subconscious. It was from a tiny house along a tinier passage off this road, that a spindly boy emerged in the mid-1980s. A boy who could not play the Veena or the violin and hold audiences at the various Dussera music festivals in thrall, as you might expect; or even sing in mellifluous mastery, the kritis (lyrics) of the greats, Purandara and Kanakadasa, as is the wont of many a Mysorean. But surprise of surprises, he could hurl a cricket ball at a speed that had not been generally seen in the whole of India for a long, long time, and definitely never in the ancient city of Mysore! The boy's name was Javagal Srinath!

The fastest 'vegetarian' bowler in the world; the spearhead of the Indian bowling attack; a class act; a man who always, as if by law, gives us the initial breakthroughs; a bowler, who, on his day, can be quite unplayable; someone who has tormented great batsmen around the world; a performer who has undoubtedly given our mostly pathetic bowling attack a semblance of respectability; a bowler who puts a sense of caution in the minds of even the most cavalier of batsmen; a man who has consistently excelled in arguably the second most demanding task -- apart from opening an innings -- anyone can perform on a cricket field -- pace bowling -- and especially on subcontinental wickets, which seem like they were carved out of the same earth that also went into making cemeteries!

Talking of wickets, the one on which Srinath began to release his express fast deliveries with that open-chested, free-wheeling action of his, at the Marimallappa High School, which was in the direction of deep point, if you stood facing his house on Ramavilasa Road and at almost the same distance at which you would find that fielding position from the crease on a cricket field; was not really anything like the greens of England but more, I must say, like the arid, war ravaged fields of present day Afghanistan!

The school authorities, in their weighty wisdom, did not at any point, feel the need to either make an attempt to add a touch of green to the playing arena or even sprinkle a bucketful of water on the dusty, pebble-ridden stretch of earth that was known as the school's cricket ground, because they perhaps felt that not a single student from their school had it in him to play the game of cricket with any noticeable quality. A school had to just have a ground and this was it. More to fulfill the guidelines of the Directorate of Public Instruction than the passions and dreams of young boys who still, in spite of the ravaged ground, put bat to ball, no sooner than the sounding of the last bell, announcing the end of classes, every day! It is hard to believe, even harder to digest the fact, that one of the greatest fast bowlers of our country emerged from a city, which was more known for its music, perfumes and paintings than any serious cricketing ambience, compared to cities like Bangalore, Chennai, Mumbai and many more. With grounds like the one in Srinath's school, the city couldn't have been world famous as a cricket nursery anyway!

But who, just who, ever thought that this boy would put Mysore on the world map of cricket and make batsmen smell leather instead of agarbathies, (incense sticks for which the city has a big reputation), make them dance to his own tunes (quintessentially Carnatic, should I say!) and even paint all by himself a painting, (Mysore style!) that showed a top quality pace bowler, who stood at the start of his bowling mark and put the fear of the unknown in them.

Much water has cascaded down the 'Kannambadi Katte', the Krishnaraja Sagar dam, less than ten kilometers from Mysore as the crow flies, since Srinath took his seat on a Qantas jumbo jet flying in the direction of Sydney, back in the season of 1991-92. That was the year in which he made his Test debut for India against Australia. The legendary Kapil Dev was still wearing his white flannels for the country and a raw Srinath had a lot to learn on the tour. So what if the television screen showed the rookie as a study in helplessness, confusion and disarray every time an Aussie batsman smashed him for four. So what if he was as erratic as a bucking horse and a few of his deliveries were so off target that they went way down the leg side while they were expected to pitch on and around the off-stump.

So what if Srinath could never judge a run without shuffling and then stuttering and stammering a 'yes, yes, no, no' in such comical fashion. "All this is a part of him I guess. He is, for all you know, made like that," says K.R. Dinkar, a fellow Mysorean, and a fine fast bowler himself, under whose tutelage young Srinath learnt a trick or two in the mid 1980s.

Dinkar also told me about how Srinath, playing for Mysore Gymkhana against the formidable Bangalore Union Cricket Club (BUCC) back in 1986, at the MICO Grounds in Bangalore dropped a sitter, giving the hard hitting Syed Kirmani, a lease of life. Asked why, Srinath pointing to the great wicket keeper and cupping his hands to his mouth in sheer awe, replied, ' 93 Tests!' Was it his initial tendency to be overawed by a crunch situation on a cricket field or plain reverence for the veteran that made him drop the catch? One will never know.

But he is also made, we must not forget, to come up with a peach of a ball, a beauty of a delivery just when things are beginning to look a tad predictable. Like the one that got Allan Border in Melbourne a little over a decade ago. With a combination of deliveries that beat the great Aussie's bat and also made him jump, he finally had him caught behind by wicketkeeper Kiran More off a ball that rose and kept rising from a good length, even as Border tried a last-minute manoeuvre to fend it.

Kepler Wessels, Courtney Walsh, Imran Khan, Clive Lloyd, Steve Waugh. Names that mark a succession of great deeds on a cricket field. Men of mettle who shone and lead through example. Men who rate Javagal Srinath very highly. They had to, perhaps. Because not too many of them from India have bowled a cricket ball with the same fire and intensity as a pack of gelatin sticks. As Srinath does. Don't remind me of the rotator cuff muscles in his shoulder and their fallibility against sustained use for long years. And his body's wear and tear. He is still our best bet as a fast bowler.

One of his close friends, Manoj Kumar, told me that Srinath once went all the way to Cochin in Kerala just to seek an audience with Carl Rackemann, the Aussie tearaway. That is a measure of his sincerity. A sincerity that found him bowling a cricket ball to the wall of his classroom in Marimallappa's High School, for long hours after the class had been dismissed. A sincerity that allowed him to be open-minded, even as a seventeen-year-old, when his mentor Dinakar stood at short mid-wicket and urged him to bowl on the right spot, and put his natural talent to proper use, on so many occasions during so many league encounters in Mysore and Bangalore and Hassan.

One of his close friends, Manoj Kumar, told me that Srinath once went all the way to Cochin in Kerala just to seek an audience with Carl Rackemann, the Aussie tearaway. That is a measure of his sincerity. A sincerity that found him bowling a cricket ball to the wall of his classroom in Marimallappa's High School, for long hours after the class had been dismissed. A sincerity that allowed him to be open-minded, even as a seventeen-year-old, when his mentor Dinakar stood at short mid-wicket and urged him to bowl on the right spot, and put his natural talent to proper use, on so many occasions during so many league encounters in Mysore and Bangalore and Hassan.

Srinath is a man who is a bit of a riddle. A kind of enigma really, in the present context of all the hype, the adulation, the flash bulbs and the fan following that all combine to make superstars out of some very ordinary men with very little to show on the score card at the end of day's play. But Srinath is a thoroughbred achiever. A man who has gone on to stamp his class from the Wankhede to the Wanderers, from Melbourne to Motera, from Brisbane to Bangalore. And for so long a period, in a game which is played almost throughout the year with no breaks, except perhaps for drinks and lunch! And in a team, with its own brand of intrigues, selected by a bunch of selectors with their own special talent to blow the whistle to signal the start of a round of musical chairs if they so wish!

And yet for all his achievements, Srinath is unrealistically simple in his ways. In spite of having rubbed shoulders with some of the greatest players of the present era. In spite of playing a game, and very successfully at that, which not less than a billion Indians (give or take a few millions!) consider as religion, and for a country that considers its cricketers as children of a greater God, a God far superior to the multi-million Gods of the pan-Indian pantheon put together!

I see him driving around in a not-so-good-looking Maruti 800 (when nothing less than a swank Mercedes Benz or some such luxury accoutrement will do for most of his team mates) every time he is in Mysore, mostly between two series; or watching him eat ice-cream with an old friend or two at a road side kiosk; or even better, coming down to the Mysore Gymkhana team's 'katte' (a stone bench, typical of Mysore and Mysoreans, where friends meet regularly) on Geetha Road in the middle class extension of Chamarajapuram, which portrays the ethos of the city so wonderfully well; or playing tennis ball cricket in front of his old house in that tiniest of passages off Ramavilasa Road, where hitting a ball for four is just a matter of patting it to a distance, all of two and a half feet to the sides of the wicket! I'm sure Srinath always bags a handful of wickets and more, bowling in that passage. He should, I guess, considering that he has bagged a lot more playing in an arena, a million times bigger, and against batsmen, who could easily hit, let's say, 456 boundaries, every time they took guard in that passage in front of his house!

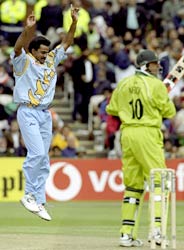

The very same Srinath has a mind-boggling 300 wickets in one-day international cricket. He should have got the 300th in New Zealand but he dropped a lolly, and saved it for India's first match in the present World Cup. A game, ironically for Srinath, against Holland, a team that is so much like a newborn wilderbeest calf in the unforgiving wilds of the Kruger National Park, and as helpless too.

As the number '300' is fixed along side Srinath's name, it will perhaps narrate the fascinating story of a young, gangling boy who once, as a spectator at the Maharaja's College Ground in the small city of Mysore, had exulted in uncontrollable glee at having fetched a ball from the boundary that had been hit by a man called Roger Binny. A boy, who was thrilled, just because he had 'touched' a ball hit by an international cricketer!

Sunaad Raghuram is the author of 'Veerappan The Untold Story', Viking, 2001

More Columns

Schedule | Interviews | Columns | Discussion Groups | News | Venues