| « Back to article | Print this article |

'How come with Nehru at the helm, India missed so many buses? He had such unchallenged power that he could have taken the country in any direction he wanted. The sad conclusion is inescapable that Nehru let things drift in true Hamletian ambivalence,' says B S Raghavan.

'How come with Nehru at the helm, India missed so many buses? He had such unchallenged power that he could have taken the country in any direction he wanted. The sad conclusion is inescapable that Nehru let things drift in true Hamletian ambivalence,' says B S Raghavan.

Part I: The Jawaharlal Nehru I knew

The one event that simply devastated Nehru was the Chinese attack on India and their advance deep into Assam, routing the Indian Army everywhere.

To rub in their superior might and command of the situation, they declared a unilateral cease-fire and withdrew from the territory they had occupied with little resistance from the Indian side.

Nehru could never recover from the humiliation inflicted on his and the nation's psyche. I stood by his side when, with tear-bedimmed eyes, he confessed to a media conference at Vigyan Bhavan that he had begun to live in a world of make-believe in regard to China. I saw many wiping their tears and needless to tell, I was myself in tears.

The Chinese betrayal drained all the energy of this once young person of 75 years who, even at that age, used to bound up the stairs two at a time. From then on it was a slide downhill both in terms of his vitality and grip over persons and issues.

However, he did make one momentous move to bring about a rapprochement with Pakistan and write finis once and for all to the fouled up relations between the two countries, especially over Jammu and Kashmir.

With uncanny shrewdness, to play the mediator, he turned to Sheikh Abdullah whom he had kept imprisoned for more than 12 years over an untenable and concocted case of conspiracy against India.

The outpouring of tenderness and affection of the first meeting between the two, who were once bosom friends, soon after the Sheikh's unconditional release, cannot be recounted in words.

Sheikh Abdullah readily agreed to try to bring Pakistan round to a receptive and reasonable frame of mind and left for Rawalpindi.

Meanwhile, Nehru went to Dehra Dun for a holiday. On May 25, 1964, a day before he was set to return to Delhi, correspondents asked him whether he was hopeful of ushering in an era of amity and harmony with Pakistan within his life time. Nehru replied good-humouredly that there was not the slenderest chance of his lifetime ending that soon. He returned to Delhi the next day and was dead the day after.

How come with Nehru at the helm, India missed so many buses? He had such unchallenged power that he could have taken the country in any direction he wanted. For instance, he could have replaced wholesale the trappings and shackles of British Imperialism against which he used to revile, brought about revolutionary reforms in every sphere and made a clean break with the past on many other counts too so that the values cherished and nurtured during the freedom struggle were built into the ethos of India.

The sad conclusion is inescapable that Nehru let things drift in true Hamletian ambivalence.

Take the question of open government and civil liberties: Nehru did take time to record his revulsion in respect of a dozen or more cases where files were put up to him with pompous notings insisting on maintaining the secrecy of the action proposed, and to veto in the choicest phrases proposals for dismissal or preventive detention based on nothing more than reports of subordinate police officials.

On many papers marked as Top Secret, Secret etc, he himself struck off the classification and downgraded them, letting fly some well-deserved barbs against excessive obsession with secrecy.

He erupted like a volcano at any attempt by the Intelligence Bureau to block an appointment on the ground of past anti-government activities or security, and poured out all his righteous wrath, condemning the colonial police mentality, saying that, in that case, he should also be regarded as the greatest danger with no right to continue as the PM!

For all his acute sensitivity where civil liberties were concerned and his direct experience of the colonial oppression, Nehru could never muster sufficient will to direct a determined and sustained attack on the system with atrocious anachronisms such as the Official Secrets Act, negating the very concept of openness and freedom for which he fought all his life.

His occasional edicts giving vent to his displeasure and demanding root-and-branch reform were lost in the 'dreary desert sands' of the dead habit of secretariat bureaucracy in the absence of follow-up by a personal office (PMO) of the kind his daughter had fashioned for her own purposes.

He was largely content with putting his foot down against future encroachments (as when he violently reacted against legislating a Treason Act) but did not implant a concerted policy or a consistent philosophy of liberty.

It is a tragedy that one like him who sacrificed and suffered so much against the inequities of the colonial system should have left so much unfinished business in a sphere so intimately connected with individual liberties as protection of privacy, openness of government and safeguards against the misuse of their powers by intelligence and investigative agencies.

Nehru also let his half-baked socialist susceptibilities and prejudice against capitalist America get the better of him to the detriment of India. He could have easily maintained his policy of non-alignment and equidistance between the two power blocs without rubbing the US on the wrong side so often and to such little purpose.

With his tremendous prestige as a freedom fighter of heroic mould on par with the heroes of American history itself, little gestures of overt friendliness to the US on his part would have fetched disproportionate benefits -- vastly more than what he was able to get from the Soviet Union.

Surely, in this sense, the era of Indo-US relations as he shaped it became one of missed opportunities.

Nehru's critics have been unsparing in blaming him for his mishandling of the Kashmir question, putting his unquestioning trust in China, and taking the country into an economic wilderness with what Rajaji expressively lampooned as the license-permit-quota raj.

There are many who bitterly trace the disastrous course the Kashmir question has taken since Independence to his naivete in referring the invasion of Kashmir by Pakistan to the UN and, in particular, his acceptance of the cease-fire imposed by the Security Council when the Indian Army was in a very strong position to win the first ever confrontation with Pakistan and teach it a lesson by bringing the entire Jammu and Kashmir within the Indian fold.

Similarly, he has been the target of attack by even dispassionate scholars for the Hindi-Chini bhai bhai syndrome culminating in the bloody nose India got from China in 1962, and for the legacy of the festering border dispute with China.

Holding as I did the position of a mere deputy secretary in the home ministry entrusted with the responsibility of servicing the National Integration Council of which Nehru was founder-chairman, my meetings with him were usually short and business like and it was but rarely that weighty affairs of State handled by him as PM or issues relating to Kashmir or China figured in our conversations.

Nevertheless, on the occasion (which I have already mentioned in part 1 of the article) in which I had a brush with him on an English usage, he permitted himself a sort of soliloquy, with me sitting before him, in the course of which he revealed a side of his personality that nobody suspected existed.

What I recorded in my notes immediately after I left his presence is not a verbatim reproduction of what he said, but is something close to it:

'People take me to be idealistic, devoid of any understanding of the Machiavellian realities that govern the conduct of countries and the relations between them. That is not so. The fact that from a very young age, I came under the influence of Mahatma Gandhi, has a lot to do with my approach to people, issues and nations.'

'You remember he was even for disbanding the armed forces and for India to stand forth with only trust and faith in humanity as its shield. We could not go that far, but the sheer grandeur of his ideas left its mark on my personality.'

'In retrospect, many decisions may look wrong or even against national interest. Do I regret them? At least some of them, yes. As regards Pakistan's meddling in Kashmir and border problem with China, definitely yes. But as regards the State's role in shaping the economy and the government going out of the way to win over minorities, especially the Harijans and the tribals, I think no government in India can ever afford to have any other policy.'

'Only the State had the huge resources to invest and build the basic infrastructure and the heavy industries and irrigation dams at the time of Independence and for all these years after it. They were needed to provide the foundation for progress in all other types of economic activities and social uplift.'

'Epithets like pro-Muslim etc have been flung at me, implying perhaps that I am against Hindus or Hinduism. This is utter nonsense. I am pro-minorities, that's all.'

Behind that charismatic, mobile and enticingly charming face of his, was Nehru really an artful politician?

Was the Kamaraj Plan, for instance, his crafty way of getting rid of inconvenient colleagues who had grown too big for their shoes?

Did he use Lal Bahadur Shastri as a clever decoy in putting the plan through, only to bring him back later?

Did he legitimise corruption in Indian politics by quietly turning a Nelson's eye to the unsavoury methods of fundraising that had already begun to be adopted by many Congress leaders?

These questions are sometimes asked, but I think they are a waste of time. Gandhi, who had been the mentor of Jawaharlal for more than thirty years, had no doubt about his being a genuine jawahar (jewel).

None of Nehru's critics had watched him in all moods and situations as closely as Gandhiji did and are, therefore, only giving vent to their personal prejudices. What Gandhi said should suffice for history.

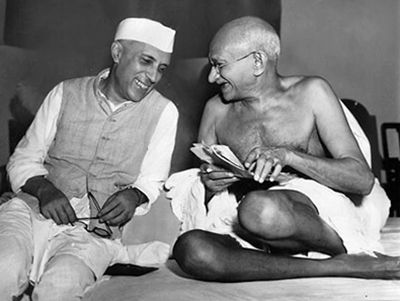

Image: Jawaharlal Nehru with Mahatma Gandhi.