| « Back to article | Print this article |

It was 40 years ago on December 16 that the world saw the biggest surrender of an army after World War II. Journalist Prem Prakash recounts what happened on that momentous day.

It was 40 years ago on December 16 that the world saw the biggest surrender of an army after World War II. Journalist Prem Prakash recounts what happened on that momentous day.

December 16 brings back many memories. For me, that day in 1971, was culmination of a journey I started early in the year by train from Delhi to Calcutta wondering as to how I was going to cover the crackdown by General Tikka Khan's army in East Pakistan.

On reaching Calcutta, I made my way to Benapole, the border post between India and East Pakistan. My colleague from Calcutta, Durgadas Chatterji, accompanied me.

I was working for Visnews, now known as Reuters Television, and the steadily emerging ANI when I was asked to cover this crackdown by the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan. The world was anxious to know what was going on in Dhaka and the rest of East Pakistan.

Pakistan had ordered all journalists out from Dhaka, which made Calcutta the only window from where one would have to make an effort to see what was going on in East Pakistan. It was not easy. When I reach Benapole, the Pakistan Army and the border guards were still there, not allowing us to cross over. So, some of us did some filming at the border and came back. It became a daily drill to drive up to Benapole or to other areas along the border and try and see what was going on. My opportunity came when one day news came in of the uprising spreading in East Pakistan and that nervous border guards and the army of Pakistan were withdrawing from the post.

Durga Das Chatterjee and I crossed into East Pakistan and saw enthusiastic crowds on the other side and a sprinkling of the armed Mukthi Bahini, revolutionaries who fought against the Pakistani Army.

We drove into East Pakistan and recorded the first visuals of the horrible crack down which the Pakistan Army had inflicted on the civilian population of East Pakistan. There were scores of mutilated dead bodies lying around. It was a horrifying site. But it was a news story that had to be told. I crossed over several times, with not a thought at the risk I was putting myself into, to film the fight that the Mukti Bahini was putting up; the liberation of East Pakistan was not an easy news story to file.

The heavily armed Pakistan Army was present in large numbers. Nobody expected the war to end so soon.

December 16, 1971, was unforgettable. I had been covering the news story relentlessly from March of that year. Through the intervening months, I had seen millions of refugees cross into India and the atrocities of the Pakistan Army on what were suppose to be their own people. With the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini now having successfully defeated the Pakistan Army, I was among the few journalists who were quietly advised to stand by in Calcutta. A phone call came around mid-day on December 16 that I was to join Lt Gen Arora's party that was departing for Dhaka to accept the surrender of the Pakistan Army.

I rushed to the airport where Lt Gen J S Arora, Major Gen J F R Jacob and other senior officers had also arrived. We boarded the waiting army helicopters. One had to be virtually tied down inside the helicopter as these were open from the back and provided fantastic aerial views as we flew over the then East Pakistan towards Dhaka.

Landing in Dhaka, we found massive crowds inside and outside the airport waiting for the Indian general and his party to arrive.

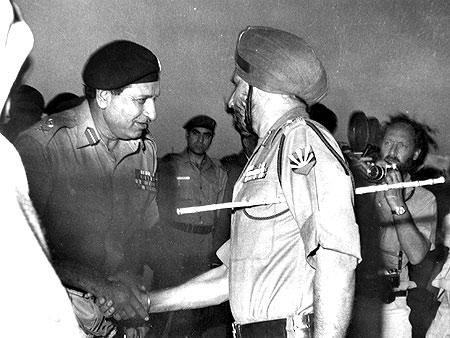

There were slogans of "Joy Bangla" in the air. We were taken almost in a procession towards the Open Ground in Dhaka where the surrender ceremony took place. Streets on both sides were lined by enthusiastic, cheering, crowds, shouting, 'Victory for Indian Army', 'Victory for Mukti Bahini'. We were all being mobbed by enthusiastic crowds, thanking India for its help. The surrender ceremony was over quickly with Lt Gen A A K Niazi handing over his personal weapon, a pistol, to Lt Gen Arora.

I decided not to return to Calcutta and managed to send back my coverage and report with another colleague who took the helicopter back to Calcutta. The world then saw the first visuals of what was the biggest surrender of an army after the World War II.

As dusk fell on December 16, the Pakistan Army, which had been allowed by the Indian Army to retain its weapons started arriving from all over East Pakistan and marching towards the Dhaka Cantonment. They were marching very fast, faces stricken with fear as the local population looked eager to attack and lynch them. The Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini had enforced a curfew to keep the crowds off the streets.

The sight of the trooping of the Pakistan Army, a fearful and dejected army, on December 16 is etched in my memory. They had never envisaged a defeat in this war. In other parts of Dhaka, throughout the night, there was noise of gun shots as snipers tried to take out lurking and hostile Pakistani troops or police. The shouts of "Joy Bangla" rent the air, throughout the night.

Next morning, from the window of my hotel room, as I woke up, I saw Indian Army tanks in position in the streets of Dhaka and large crowds of Bangladeshis cheering them, garlanding them and shaking hands with them.

A new nation Bangladesh had been born. My journey that began on a train in March of 1971 concluded with this huge victory by the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini and the emergence of Bangladesh.

Image: Pakistan's Lieutenant General A A K Niazi, left, greets Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, GOC-in-C, Eastern Command