| « Back to article | Print this article |

Peter said he needed a broom to sweep his cell because, he joked, there are no vacuum cleaners in jail.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

Illustrations: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

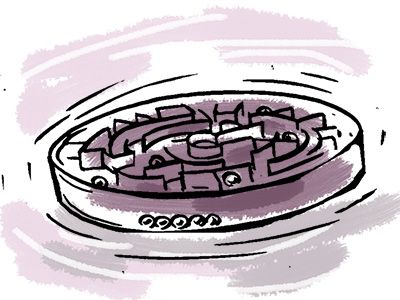

Every court hearing, one discovers, has a ball-in-a-maze kind of aspect to it.

Remember that labyrinth game one played where the object was to get all the tiny silver balls into the centre compartment and not let any of them roll back out?

When one sits on a hard, wooden bench outside the courtroom waiting for all those required for a hearing to reach Courtroom 51 at the Mumbai city civil and sessions court, Kala Ghoda, south Mumbai, one's mind returned to that cute, little, while-away-the-hours game one played.

Each time one herded almost all of the shiny silver balls into the centre, one of them, doggone it, would slip out and wander away, giving the rest the ditch. Each time it seemed like all the participants of a hearing had reached courtroom 51, someone slipped away.

At noon on Tuesday, January 22, the time set for the Sheena Bora murder trial hearing that day, only the judge and Sudeep Ratnamberdutt Pasbola, Indrani Mukerjea's trial lawyer, had reached.

No sign of the witness. Nor of any of the accused. Nor of the prosecution. Or of any of the other lawyers.

Pasbola peeped in at the mostly empty room at 12 pm sharp and exited.

He stopped to chat for half a minute with the purple-shirted Radha, the gentleman handling Indrani's personal affairs, who was already waiting on a bench for her with a bag of legal documents, and then the lawyer strolled off down the corridor, his hands behind his back, to check in on another matter of his in another courtroom.

Fifteen minutes later, a crowded jail truck roared into the courtyard below and Peter Mukerjea, Accused No 4, and Sanjeev Khanna, Accused No 2, disembarked along with a motley bunch of other prisoners from the Arthur Road Jail.

Indrani didn't arrive till 12.30 pm or so. She got off a Byculla jail van with her police escorts and another fellow female jail inmate, and briskly sailed up the path, walking furiously fast, her hair flying, wearing a white blouse, brown jeans and brown slip-ons, like she was late for a business meeting, probably certain she had missed a substantial portion of the hearing, when it didn't seem it would begin for another good half an hour or more.

By then the prosecution had arrived -- CBI Special Prosecutor Kavita Patil in a beautiful white and black, crisp Bengali sari -- and most of the other lawyers, including Shrikant Shivade, who is defending Peter.

Peter's lunch bag too had reached, brought by the cheerful Skanda Balasubramaniam, the son of an old Mukerjea family friend. On days when Peter's sister Shangon Das Gupta is not able to make it, his lunch of usually burger-fries and a surprise sweet treat, unfailingly appears, brought by one well-wisher or another.

Sanjeev's tall, athletic-looking, photographer cousin rarely misses a hearing either, thoughtfully brightening up his day, by bringing always a sandwich and a few thrillers in his backpack for him.

Meanwhile, prisoners kept filing in with their police guards. All kinds of hard-up, unfortunate types, many very young, confused to be in court and bewildered about their fate in life.

The third floor is rather busy and full these days because several of the courtrooms are doubling up for other courtrooms, as those are being renovated.

Suddenly at 1-ish, one of the ceilings started leaking water. An employee of the muddamal next door (where court exhibition items are stored) exclaimed in Marathi: "Ge la, ge la (gone, gone)" and waved his hands about in amused despair to indicate one didn't know how long the building would last.

He spoke about how rundown the surroundings were and about the "danger walla kursi" (collapsing chairs) in the courtrooms.

Indrani was shuffling through her legal papers with Radha. The paperwork for her divorce, and the attendant distribution of assets, keeps her exceedingly busy and engaged these days, like it did on Tuesday, as she scoured through one stamp-papered document after another and often came charging across to the other section of the corridor, trailed conscientiously by her young and slightly exasperated woman police guard, to argue frustratedly with Peter about the procedure or something else.

"But they are not responding!" she wailed, as Sanjeev, wearing blue checks, sat grinning, good-naturedly, probably thinking what a relief it was to already be an ex-husband and unattached, although his links with a former wife have taken him away from his home, his city and his family, including an elderly parent.

It was difficult to resist the temptation to eavesdrop because Indrani has a knack of arousing curiosity. All the assembled police guards of the trio, about 12 of them, gawked, listening open-mouthed to the discussions between husband and wife, even as Peter tried to keep the lid on things.

Witness 28 Dr Yusuf Abdulla Matcheswalla, 60, ambled in at about 12.45 pm, well-shaven, wearing a white shirt, a black vest, black trousers, black shoes and a watch. Like the start to a stage drama, by 12.45, most of the cast of actors for Tuesday's hearing were waiting in the wings. Except Pasbola.

CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale, now impatient, questioned the assistants, asking where the advocate had got to. They went darting off in different directions to locate him, in this behemoth beehive of a building.

Dr Matcheswalla parked himself on a bench to have tea with great gusto, something he sorely missed at the previous hearing. And everyone sat about to wait, knowing that one missing actor/player meant usually a long delay.

Two years in these corridors has taught one tremendous fortitude. The endless waits have long ceased to matter or vex although that is so dreadfully easy to say when you are not the one in jail in judicial custody, and the most unfortunate cog in our byzantine legal set up.

When I set off for Thursday's hearing, a cousin, who had returned to India from the US for a visit after an extended gap, asked, shocked: "Is that murder case still on?! It has been two years."

It might be two more years or more. How do you explain that to someone who has never sat in these hallways and understood how difficult it is to get all the darn silver balls into the centre of the maze and doing their job?

At 1.15 pm Pasbola hurried in, apologising profusely. Pasbola quickly picked up from where he had ended last Thursday discussing the treatment Indrani's second child, the recently married Mekhail Bora, received from psychiatrist Dr Matcheswalla, who once ran the psychiatric unit at the Masina Hospital, Byculla, south central Mumbai.

A small rewind: Mekhail in his testimony in 2018 had done his bit to blacken his mom's reputation by suggesting she had had him certified as mentally ill and clapped into a mental hospital so she could eventually get rid of him. Pasbola has been unpacking that episode for the court via the doctor.

While one might blame the lawyer for delaying proceedings, one has to be in awe of his ability to switch from one case to the next, without a hitch. How does he keep track of all the details and strategies? Are his assistants briefing him as he rushes, swift-footed (from all that golf), from one courtroom to the next?

Pasbola began by asking about the availability of risperidone, the medication prescribed to Mekhail, six years before Sheena's murder, for what was diagnosed by Matcheswala as substance-induced psychosis (when a psychoactive substance causes psychotic symptoms in an individual).

He wondered too about the validity of a prescription.

After his discharge in 2006 from Masina and return from the rehab facility at the Chaitanya Mental Health Care Centre, Katraj, Pune, nine months later, Mekhail would have come home with a prescription for this medication.

Dr Matcheswalla: "When I write a prescription I have to write the period also -- one month, two months (etc)."

Pasbola: "In short, sir, it cannot be used again and again?"

Dr Matcheswalla: "Can be used till the period of time mentioned on it."

The lawyer wanted to know how hazardous risperidone was.

Dr Matcheswalla, emphasising each word: "In therapeutic doses risperidone is fairly safe."

After the time-consuming, tedious, squash game Dr Matcheswalla and Pasbola played in court last week, where the ball went all over the place, the Q and A got quickly into the groove on Tuesday, with Judge Jagdale diligently and super-alertly playing referee, summarily cutting Dr Matcheswalla short, just as the psychiatrist opened his mouth to start an elongated discourse on any aspect of psychiatry.

Pasbola confirmed Dr Matcheswalla's cell phone number in 2012 and if he made/exchanged a few calls and messages to/with "Mrs Indrani Mukerjea" in April that year with regard to "medical advice to her and her relatives."

When it came to the details of the treatment he had offered Indrani herself, Dr Matcheswalla was vague. He didn't remember the exact date she consulted him, but recalled that she had hypertension or an anxiety disorder. He couldn't recall what he prescribed for her as an anti-anxiety medication.

Pasbola, instead of trying to shake an answer out of the doctor or attempt to forcefully jog his memory, cleverly asked Dr Matcheswalla "What is generally the medication you prescribe as an anti-anxiety?"

Continuing, the advocate, in a teasing mood, asked what would be the medication Dr Matcheswalla would prescribe CBI Special Prosecutor Bharat B Badami for his anxiety.

Badami looked startled at Pasbola, his quizzical expression indicating he had maybe never suffered from anxiety.

Dr Matcheswalla, not hearing the joke: "It would be a combination. Mainly benzodiazepine and SSRI (that stands for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, a family of drugs used as antidepressants)."

He spelled the medicine out carefully. That way the doctor was a dream witness, methodically and slowly enunciating his view and expressing his answer clearly, dictating it to the judge.

The lawyer stuck in a question that must have been on everyone's minds at the last hearing. He enquired about the kind of advice Dr Matcheswalla gave to people over the phone and SMS and if it included advice about medication.

Dr Matcheswalla dodged the query a bit by adding a lengthy, methodical run-up to his answer: "It could be some advice related to the medical condition (of a patient). It could be related to passing some phone number. It could be availability of my appointment and in an emergency situation some advice regarding medication."

Pasbola carefully understood from Dr Matcheswalla how he came to a diagnosis, a decision to hospitalise and if he treated a patient when: 1. the history given differed from his evaluation and 2. before he had arrived at a diagnosis -- he did both.

Moving it to specifics, Pasbola checked if the same procedure was applied to Mekhail. His effort to ascertain this was hampered by interruptions by Badami and by Dr Matcheswalla's verbal acrobatics whereby he answered only different parts of the questions and not the entire question.

Pasbola about Badami: "Don't go by what he is (suggesting). He is trying to confuse you."

Badami, irritated: "No, no!"

Dr Matcheswalla continued to prevaricate, Pasbola continued to try to pin him down and request him to answer, Badami continued to defend his witness.

Dr Matcheswalla: "Na, na, na. Not going by your diktat."

Badami: "Cannot dictate."

Impasse.

Judge Jagdale blew his whistle, and in a good-humoured way, took over the cross-examination sorting out the snarl in conversation traffic.

The judge to Dr Matcheswalla: "If you have not done so, say so point blank, then I will take your explanation."

Dr Matcheswalla: "I will stick to my story."

Judge Jagdale: "Stick to your story, but first answer!"

Pasbola: "You observed, evaluated and then investigated him (Mekhail) and felt he should be hospitalised?"

Dr Matcheswalla: "No after he was hospitalised," and went on to explain that medically one sometimes hospitalised a patient before investigating, just like one did for someone who comes to a hospital with chest pain.

Pasbola, roundly: "Someone with chest pain will not come to you, sir."

The lawyer wondered if the decision to hospitalise had been the right one.

Dr Matcheswalla: "My decision was absolutely correct."

Pasbola wanted to know if while he was hospitalised did Mekhail attack a ward boy at Masina.

Dr Matcheswalla, always a tad flamboyant, began answering with a flourish: "To the best of my memory... (he paused dramatically) I do not recollect."

Pasbola laughed outright at his answer and the court joined him.

Dr Matcheswalla puzzled: "What was the joke?"

Pasbola ploughed on checking if, as Indrani's son said in his testimony, if Mekhail's head could have been shaven while he was at Masina Hopsital and if he had been beaten up.

Dr Matcheswalla, talking about patients in general, explained that if a patient had not bathed in a while and had lice when he arrived, his head might have been shaved and said: "Patients are never beaten. No violence used against them. If a patient is violent he is physically restrained. And chemically restrained. Injection."

Pasbola wondered -- "as we see in the movies" -- if electric shocks were given at Masina and if Mekhail was subjected to them.

The portly psychiatrist drew himself up to his full height and said primly, correcting Pasbola's terminology: "ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) is a very scientific (method) of treatment. It is definitely used at Masina Hospital and all psychiatric centres. Not like what we see in the movies... Scientific treatment. Most effective treatment."

Dr Matcheswalla, who came across on Tuesday as a sharp proponent of ECT (which has always attracted controversy since doctors now prefer anti-depressants and because the WHO suggests ECT be done only with a patient's consent, when obtainable), added that it was majorly indicated for patients suffering from severe depression, suicidal depression, psychosis and obsessive compulsive disorder and that "Mekhail Bora also underwent ECT."

Pasbola then introduced the name of a young friend of the Mukerjeas, B*, to the court and asked the psychiatrist if he remembered a patient of that name.

Peter winced sharply when the name was brought up. Again, one wondered about the ethics of discussing the details of a patient who is neither a witness nor an accused nor the victim.

Dr Matcheswalla didn't recall the name.

Pasbola suggested that the calls between Indrani and Dr Matcheswalla in April 2012 were on behalf of B* who had issues with drug abuse.

In his testimony last Thursday, Dr Matcheswalla stated that there had been several calls between him and Indrani in April 2012, the last at a time after midnight about the medication not working on Mekhail and about Sheena being aggressive and the need to bring one of them to Masina the next day.

Pasbola pointed out that these exact details, as portrayed by the psychiatrist in court, were not in his statement to the police and in his first statement to the CBI and only appeared in his second statement to CBI.

Dr Matcheswalla, shaking his head, his brow furrowed reacted with: "I may not have recollected it then. But there was communication (between him and Indrani)," and he then tentatively asked if he could see the Call Data Records.

Judge Jagdale quickly disabused him of the idea of analysing the CDRs and said abruptly: "Mister, you have to (answer)" and said that if they sat down to look at the CDRs "he (Pasbola) will be cross examining you till 5.30!"

It was well past 2 pm and the lunch break had been pushed back so the cross examination could be completed in spite of the initial delays and everyone was getting slightly crochety, including the clerks.

The judge took a break of just 15 minutes in between, maybe to have chai as did Dr Matcheswala who wanted to visit the GT Hospital in the ten minute recess, but was forbidden.

In his Marathi statement to the Khar police station, north west Mumbai, who started the investigation into Sheena's murder, Dr Matcheswalla had said "Mekhail was completely addicted to drugs."

Dr Matcheswalla denied that, saying he was misquoted and they had not understood him. He mischievously smiled and said in any case he had not sworn on the Koran or the Bible that time.

Judge Jagdale laughed.

Pasbola commented that Dr Matcheswalla had a very "Hollywood movies" style of giving an oath in court.

The doctor asked why there were no longer a Gita or a Koran or a Bible to swear on in court. The judge explained that had all been changed.

Shivade joked about how once people swore 'to tell the truth or help me god' and wondered what god could do if they didn't. Laughter.

Finally, Pasbola put it to him that Indrani Mukerjea had been calling him that night in April 2012 about "B" and the last call was not after midnight and that portion of Dr Matcheswalla was all "false" had been "cooked" up by the CBI for him to say.

Dr Matcheswalla looked flabbergasted at Pasbola. Judge Jagdale quickly assured him that Pasbola's charge was all part of technical procedure and he needn't get angry.

The doctor then relaxed, although he kept rocking on his feet, his hands behind his back, surveying Pasbola.

He insisted that he had advised Indrani to bring Sheena to Masina Hospital the next day. His mention of Sheena this time complicating his version further.

The senior advocate announced he was done and picked up his papers and moved the little lawyer desk, which they use to place their legal papers while cross examining, over to Shivade, and sat down.

Why Shivade found it necessary to examine the psychiatrist of Peter Mukerjea's wife's (soon to be ex) son, with whom he had had almost no trucking, was not clear. Shivade, like always, kept his queries to a minimalist few. His line of questioning implied a yet undecipherable strategy that will get revealed at a later date.

Shivade: "There has been considerable research on the effect of drugs on memory, perception and sense of moral responsibility."

Dr Matcheswalla agreed with its effect on memory and perception, but said "the third point I am not aware."

Shivade probed the nexus between drugs and the cognitive faculties to tell the truth.

The 'cross' went all over the place after that, to the judge's dismay. Shivade was talking about those drugs that are referred to with an evil, capital "D" and didn't explain he was talking about to addictive drugs and Dr Matcheswalla thought he was referring to any kind of medication and could therefore not comprehend the question and seemed to be about to use that opportunity to start to wax and wane on an extraneous topic, maybe the families of drugs etc.

Judge Jagdale hastily intervened and implored: "Doctor, doctor!"

Pasbola saved the day by interjecting with the right term: "Illicit drugs."

The psychiatrist's view coincided with Shivade's.

Shivade: "Narcotic addicts are disposed to twisting the facts and telling outright falsehoods."

Dr Matcheswalla concurred and said: "Drug addicts are big-time manipulators." And said they suffered from personality disorders and were psychopathic.

Till date all addictions that had arisen in this trial had been about the now relatively decently regarded cannabis and nicotine. Narcotics is the new character who might be given a proper introduction later, if at all.

Shivade, reading from a sheet, on those addicted to drugs, underlined: "Morally depraved and inveterate liars."

Judge Jagdale was having difficulty dictating the terms to the stenographer. Shivade passed him his sheet. Badami wondered aloud why he had not got such a sheet on research about drug addicts.

Dr Matcheswalla of the same opinion: "(They) don't have any moral values."

Shivade asked if a drug addict has access to a steady supply of his drug he can "act" normal.

Judge Jagdale, injecting some subtle humour, said to Dr Matcheswalla about Shivade: "He is the lawyer of many actors."

Dr Matcheswalla answered that it was "difficult to act (normal)" but seemed to concede that for all practical purposes they could appear normal.

Shivade's enquiries and personal research into the Character of Drug Addicts ended there. The topic of finishing the arguments for Peter's bail came up. Shivade was ready to go ahead right then.

Badami, requesting more time, was violently opposed to arguing it on Tuesday and declared exaggeratedly: "Peter's Bail Application! I don't want to take any chances."

It was put off till Wednesday, January 23. Would the arguments be completed, at this rate, before the elections, one wondered? Why the delays?

Badami announced that he was continuing on the doctor theme and would bring several doctor witnesses together in a row and the next physician would appear on Monday, January 28.

Peter ate his lunch after the hearing and had another visitor who brought him a jhaddoo (broom). He said he needed a broom to sweep his cell because, he joked, there are no vacuum cleaners in jail.

He and the other accused left for jail at 4 pm-ish. He carrying his acquisition: The new broom.

*Name concealed.