| « Back to article | Print this article |

Balbinder Singh Dhami, who has played an inspector, for over a year, in The Zee Horror Show, took on the role of a witness on Monday. It was a part he had no experience of.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

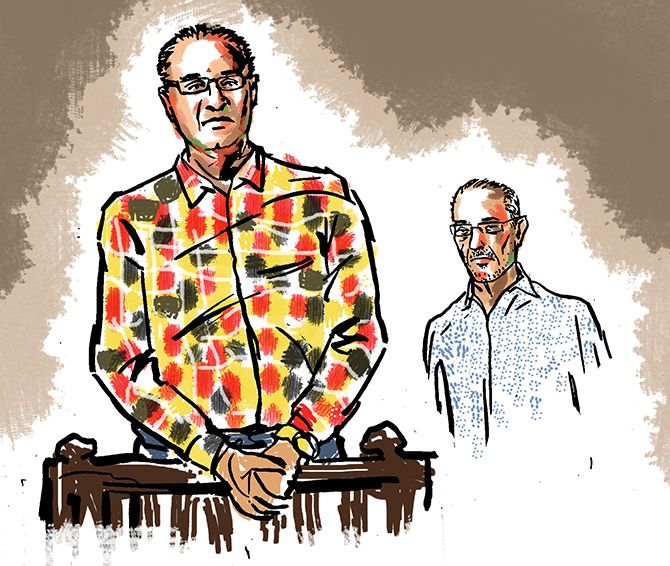

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

The witness box in CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale's Courtroom 51 in the Sheena Bora murder trial has been graced, from its start, by witnesses of all professions.

A chicken farmer. A police commissioner. A psychiatrist. A body builder. A waiter. A secretary. A chauffeur. A shoe salesman. A hotel receptionist. A luggage seller. A sari store owner. A car dealer. And more.

Monday, January 28, 2019, saw at the Mumbai city civil and sessions court, Fort, surprisingly, a Bollywood actor step up into that three foot by three foot stand, which has wooden slatted railings and a backless rudimentary stool placed in it.

Balbinder Singh Dhami, 51, who has played bit parts in Jaan Tere Naam (1992), Sainik (1993), Parwane (1993), Lalchee (1996) and an inspector, for over a year, in The Zee Horror Show, took on the role of a witness on Monday. It was a part he had no experience of.

When he began his testimony, within a few minutes, it became quickly evident that this witness was Accused No 2 Sanjeev Khanna's friend from Kolkata.

Not that he was an actor.

The stagey, slightly affected air about him, where every answer he delivered was stilted and more like dialogue, should have given it away.

But he did it himself when he consequently announced to the room first that he was a businessman and later, in a not quite off-hand enough tone that he was an actor.

In a murder case it would maybe not be astounding at all for the accused to come face to face, once more, with practically everyone and anyone they ever knew in their life, past or present -- be it their barber/hairdresser, their dentist, old pals, their house help, their mechanic, the liquor store owner from whom they bought their weekly quota of say vodka, their pharmacist or an old actor friend.

Any of them can be invited to court and called on to verify an accused's character or his life trajectory. For the accused it must almost be like pressing the button for a small life rewind, where, in quick succession, all the faces who ever coloured your life blurringly rush past you.

Dhami, a tall man, clean-shaven, dressed in a yellow, red, black and white graph checked shirt that hung untucked over blue jeans and brown slip-ons, spoke in a strong, firm voice, with perfect diction, in English, although he offered to speak in Hindi or Punjabi (and if one heard right Bengali too). He was also sporting a chunky gold watch, a gold ring and stylish, narrow black-and-silver glasses.

His wife Kanwaljeet and toweringly tall son Jaikaar came with him to court and took the last bench, exchanging warm greetings with Indrani Mukherjea and Sanjeev Khanna, whom they had probably not met in years.

Dhami and Sanjeev met around 1984 or 1985 (he was not sure of the exact year) through mutual friends T P Ray and Manglesh Jalan. He later met "Sanju Khanna's wife," as Dhami referred to her, after Sanjeev married Indrani Bora and they were living in Howrah, perhaps at the flat Sanjeev apparently owned near Shalimar station.

Indrani was running an HR/placement agency named INX and a few years after they -- Dhami and the Khannas -- made acquaintance, she was called to Mumbai by the late adman Alyque Padamsee. According to Dhami: "Alyque Padamsee was the main guy who brought Indrani to Mumbai."

Dhami, who was in the advertising business and by then had also shifted to Mumbai, agreed to become partners with Indrani who was hoping to open an HR office in Mumbai. He offered her office space on a "50:50 of whatever profit sharing" basis in "just good faith." Where that office was located was not revealed.

Indrani moved to Mumbai and in with Dhami's family -- his son, his daughter and wife. The year was 2001 or 2002, he thought.

A little later -- a year probably -- Sanjeev and the couple's approximately 2-year-old daughter Vidhie Khanna joined Indrani in Mumbai, as per Dhami's testimony.

Around that time there seemed to have been differences building between Sanjeev and Indrani. And the charming Indrani had met Peter, then CEO, Star India Pvt Ltd.

CBI Special Prosecutor Kavita Patil, who was conducting the 'testimony in chief' of the witness: "Mr Dhami, from your house where she (Indrani) shifted?"

Dhami: "She moved directly to Peter’s house along with her daughter."

Patil: "Mr Dhami, what happened to their (Sanjeev and Indrani's) relationship?"

Dhami: "After that they were going for divorce, a mutually agreed for divorce."

Patil: "After divorce, what she did?"

Dhami, looking utterly baffled at being asked such a strange question: "She got married to Peter! And I attended their marriage."

From then onwards Sanjeev was prevented from having access to his little girl.

Dhami emphatically, in a serious, sombre tone: "Khanna, (correcting himself) Sanjeev used to love his daughter very much. She (Indrani) never used to allow her to meet Mr Khanna. And he used to cry in front of me. He used to keep (hold) a small doll and cry for Vidhie." Maybe the doll had belonged to Vidhie, but Dhami was not asked to explain.

When Dhami was narrating the details of this sorrowful chapter in Sanjeev's life -- of an adoring father losing contact with his toddler daughter -- he (Sanjeev), wearing, Monday, a blue-and-white plaid shirt and jeans, sat pensively, aloof from the others in the accused box, either lost in thought or memories. Or sadness.

He was, after all, sharing the enclosure with the man who took his Vidhie and wife over, maybe unknowingly. And with a woman who had abandoned him for whatever reason, even if it was years ago.

This was the daughter who remained lost to him, with whom Sanjeev was never again able to establish contact, according to him, in spite of a trip in 2012 to try and see her. This was the daughter to whom Indrani had told that Sanjeev had mistreated her apparently.

This was the daughter, now nearly 21, who Peter Mukerjea adopted, with whom hopes of restoring a relationship were scant as Sanjeev continued to be detained in judicial custody in the anda (solitary) cell in Arthur Road jail since his arrest in 2015. Even on the two or three visits to court, Vidhie had not stopped to say even hello to Sanjeev.

Were they wounds that would ever heal? What was the other side of the story, Indrani's take?

The room, too, in that moment became aware of the tragedy/U-turns of Sanjeev's battered life.

Usually only the third wheel in this murder case, whose name comes up after every three or four hearings, Accused 2 once was a happy-go-lucky businessman helping restore and convert a rajbari (old Bengali zamindari mansion) into a heritage hotel at Bawali, about 35 km from Kolkata.

Before his implication in Sheena's murder (the stepdaughter who was never a stepdaughter, because he never knew about her or knew of her maybe later as Indrani's sister), Sanjeev, a motor rally enthusiast, was often spotted at some of Kolkata's clubs, as per earlier news reports and his Facebook page, and led, by all accounts, an uncomplicated life.

Indrani, in white, her hair loose, looked at him at that point, giving him a shadow of a smile. But he didn't seem to register it.

Sanjeev and Dhami remained in touch, even after Indrani speedily exited out of his life. "(After) I shifted to Mumbai, jab bhi Kolkata jaate the bakee dost se milte the aur unse (bhi) milte the (whenever I went back to Kolkata I met all my friends and him too). Can't call it a close friendship. Hi hello ho jatee (a reunion of sorts happened)."

Cut to April 2012: Dhami said Sanjeev Khanna called him to say he was coming into Mumbai and requested permission for use of a car.

Dhami, who was out of town, obliged and sent his car, and a driver named Imtiyaz, to pick Sanjeev up from the airport and take him to a hotel Dhami remembered named Hiltop in Worli.

At this point in his testimony, the actor-businessman pointedly added that that evening his driver, after dropping Sanjeev to the hotel, called to say that Khanna needed the car for a further two hours.

Dhami said he refused and asked that the driver bring the car back to his building to its rightful parking spot. It seems Dhami was living in the Tulips cooperative housing society in Oshiwara, north west Mumbai then, and still does.

Patil asked Dhami if he could identify Indrani and Sanjeev and if they were in the courtroom on Monday. Dhami said they were and pointed to them. He inserted, "Mr Peter Mukerjea is there too!" There were smiles all around.

Dhami's cross examination began with Gunjan Mangla representing Indrani, in absence of trial lawyer Sudeep Ratnamberdutt Pasbola. She had just a few questions. The most important were:

Mangla: "Mr Dhami, did you attend the wedding of Sanjeev Khanna and Indrani Mukerjea in Calcutta?"

Dhami, disapproving of Mangla's not up-to-date geography: "Kolkata."

Mangla obliged: "Kolkata."

Later, Dhami himself used Calcutta.

Dhami: "No."

A few questions later, Mangla: "Mr Dhami, did it ever happen in your presence that Mr Sanjeev Khanna asked to meet the daughter and Mrs Indrani Mukerjea refused?"

Dhami, backtracking: "I really don't remember what was going on between them."

Similarly when re-questioned in detail by Mangla about a few of the bits of his just-finished testimony, his answer was always that it had all happened very long ago and he could not remember.

Sanjeev's trial lawyer Niranjan Mundargi took over, addressing him respectfully as Balbinderji and acknowledged to Dhami that he knew he was an actor.

Like Mangla, he also had not much ground to cover given that Dhami had provided a few facts helpful for Sanjeev's defence already, like Indrani's treatment of Sanjeev after she met Peter.

His main task was to undo Dhami's statement that Sanjeev asked for a car for an additional two hours in April 2012. The specific date of April 24, the day Sheena was murdered, did not come up specifically but was alluded to all through.

That should have been a quick and easy task for the lawyer, except that Dhami had acute and genuine comprehension issues. Most of Mundargi's questions just didn't find their mark, like drunken arrows flying miles wide of the target.

Not because they weren't lucid enough, but Dhami, quite similar to a student appearing for a physics exam who didn't understand physics at all, just couldn't get them. And it didn't seem to involve any subterfuge either.

Dhami also tended to take back the statements he had just made in his testimony, minutes before, as if the court was hallucinating and he could never have uttered them.

Mundargi: "Did it happen that you used to tell Imtiyaz that soon after dropping or picking up any person as per your orders he had to park the car in your garage?"

Dhami: "Not in the garage. At my place. So there was no wasting of fuel."

Mundargi: "This Imtiyaz used to misuse the car on the pretext of dropping or picking up someone or waste time?"

Dhami, taken aback and not grasping the question: "No!"

Mundargi reminded him that in his statement to the CBI he had said that.

Dhami insisted: "I am not aware!"

Mundargi: "Didn't you state that?"

Dhami: "Ya, misuse can be for fuel consumption..."

Mundargi, giving Dhami an amused, quizzical look, mildly interjected that that was the same kind of misuse he had been referring to all along.

Judge Jagdale, in an attempt to untangle the knotted communication lines, took to rephrasing Mundargi's questions in the simplest possible language. He too could often not achieve the necessary results and in mild exasperation simply dictated to the court stenographer that the witness could not recollect, as Dhami's answer to a number of the queries.

Along this fractured, hit-and-miss path the Q and A continued and came to the crucial point of understanding the alleged request by Sanjeev to have Dhami's car for two hours extra on the evening of April 24, 2012.

Dhami agreed that he never checked with Sanjeev what the further two hours bit was about.

Mundargi: "You did not verify this fact with Sanjeev Khanna?"

Dhami: "Actually I didn't bother."

Mundargi: "I put it to you that you didn't bother to ask Sanjeev Khanna because you didn't believe Imtiyaz."

Dhami, lamely: "Won't be able to say."

Subsequently, the actor businessman, who handled each question in a sort of unrequired defensive and slightly belligerent manner, could not understand that he had been interrogated by the CBI twice.

He denied, first, ever meeting the CBI at all and finally agreed that he had given a statement but just one statement and did not quite comprehend that a statement/s were the result of enquiries by the CBI.

Mundargi: "Balbinderji, did the Khar police station (Mumbai north west) officers ever call you for enquiry?"

Dhami: "Never."

Mundargi: "On how many occasions did the CBI call you?"

Dhami said they never called him either.

Silence in the courtroom. It was, after all, a CBI courtroom.

Mundargi: "The CBI never called you for an enquiry?!"

Dhami said they only called him just before this hearing to tell him to come.

Mundargi laboured to explain what he meant by enquiry and that it was not an enquiry into anything Dhami had personally done wrong, but an enquiry in the course of the murder investigation.

Still, Dhami adamantly: "No, no enquiry. Or I might have said what I am saying now!"

Confusion set in. Dhami looking more and more puzzled. Mundargi was at a loss. And the room was in giggles including his wife.

Patil gently asked Dhami to listen to each question carefully.

Mundargi instead, turned the question around and asked how many times he visited the CBI office, could it have been 2 times or ten.

Dhami plaintively stated that he could not remember: "Itni saal purani kahani yaad nahi hai (It is such an old story. I can't remember)."

Mundargi, primly: "Kahani nahin hai (It is not a story)."

Dhami shrugging: "I can't remember. I am a businessman. I do business."

Mundargi showed his statement to the CBI and persisted with his line of questioning.

Dhami wearily: "Mera mazzak kar rahe hai? (Are you making fun of me?)?"

Judge Jagdale chided Mundargi saying the witness was scared.

Dhami: "Ek hi baar statement diya. Kasam se. Lunch karke aaya. Puch le beta se (I gave a statement only once. I promise. I ate lunch and came back. Ask my son)," gesturing to his son at the back. "Kuch yaad nahin (I don't remember anything)."

When Dhami left the courtroom after his testimony and cross-examination about 40 minutes later, he didn't look any wiser about the visits he had made to the CBI or what part of the investigative process he had participated in.

Nor was anyone else wiser about why Dhami simply could not remember/fathom what all the 28 witnesses before him had no trouble understanding.

It is not a role he should volunteer to repeat.