| « Back to article | Print this article |

'It is very hard to get the police to file a report against someone from an upper caste.'

'Things are so bad that sometimes we have to sit on a dharna with the body of a Dalit victim to get the police to file a complaint.'

Nikita Puri and Manavi Kapur report.

IMAGE: Activists stop a train during the Bharat Bandh, April 2, 2018, against the dilution of the Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe Act in Patna. Photograph: PTI Photo

In the classroom of an elite college in New Delhi, a professor begins a conversation with: "If you don't know the answer to 'What is your caste?' you are most likely a privileged, upper caste Hindu."

About 200 km away, in Uttar Pradesh's Saharanpur district, Chandrashekhar would know from experience what the professor is talking about.

While his father was a schoolteacher, Chandrashekhar and his brothers would often be heckled by upper caste Yadavs and Thakurs if the lower-caste Dalits, the community to which they belonged, refused to do their bidding.

It was this persistent harassment that led Chandrashekhar and his brother to form the Bhim Army in 2014.

And it was the Bhim Army that put up a board outside their village in Ghadkoli, taking pride in using a word that is forbidden by law and yet continues to be used as a term of abuse -- 'chamar'.

The Bhim Army is a group of young men that protects Dalits against any violence. But it also mobilises and unites a community by focusing on education with tuition centres, helping small entrepreneurs set up businesses such as the Bhim detergent powder and cultivating a sense of community that is otherwise lacking among the Dalit sub-castes.

The ripples that this gesture of Dalit pride created were felt as far away as in Gujarat, too.

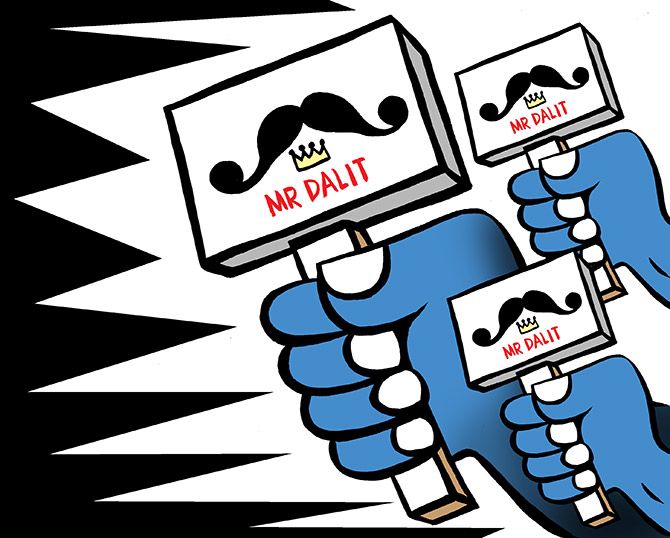

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

After young Dalit men were beaten for 'daring' to wear moustaches in the state's Limbodara village last October, the tech-savvy young community began the 'Mr Dalit' protests on WhatsApp.

Several men sported moustaches and changed their display pictures to the caricature of a moustache with a crown.

It was time to take the sting off a curse, to erase the connotation of abuse from their identity.

With social media as their tool, a young Dalit population came together to say what it had been saying individually before -- that enough was enough.

Dalit leader and Gujarat MLA Jignesh Mewani, who won the election as an Independent candidate. Photograph: Kind courtesy Jignesh Mewani/Facebook

Another newly high-profile product of this new-found assertiveness and confidence is Jignesh Mevani, the recently elected MLA of the Gujarat assembly and torchbearer of protests against the flogging of Dalit men in Una.

While leaders such as the Bahujan Samaj Party's Kanshi Ram and Mayawati appealed to an older voter base, Mevani and his co-activists belong to the tech-savvy generation that allows them to take strength from similar movements across the country.

Leaders like Mevani, Prakash Ambedkar in Maharashtra and Chandrashekhar in Uttar Pradesh, among countless others, are stitching together a Dalit brotherhood, urging them to fight a common enemy.

There is a whiff of change in the air, but there is also an embedded prejudice against Dalits that will take perhaps another generation to shed.

Seven decades after India's Independence, issues related to caste continue to plague places of education.

A mere increase in student enrolment from Dalit communities doesn't suggest all is well, says a report by the National Movement for Justice.

The case of Rohith Vemula, the research scholar from the Hyderabad Central University who hanged himself in January 2016, comes to mind.

'My birth is my fatal accident,' Vemula wrote in his now famous words in his suicide note, referring to his Dalit background and the discrimination he suffered because of that tag.

His death brought together students from across the country, taking caste-based discrimination by its horns and spelling out what is usually left politely unsaid.

Among the students who were present for a show of solidarity at HCU was Rupa Murala.

When Murala spoke of how picking on Dalits was a regular affair in their university, students who had come from as far as Mumbai and Puducherry chipped in with stories of how such biases were prevalent on their campuses too.

"If Dalit students wear new clothes, upper-caste students look at us and laugh. And our merit is always questioned. It is the same story everywhere we go," says Murala.

"The forms and faces of caste discrimination and exclusion have changed, but it is still a distinct reality," says Sreerag P, the students' union president at HCU.

It is a malaise that students admitted to a reserved seat face almost every day.

"Each university has its fair share of faculty members who come with an assumption that such students don't really want an education," says Sreerag.

These assumptions, he adds, are often followed by comments on how Dalit students are present in places of higher education only to take advantage of scholarships and fellowships.

IMAGE: Dalits block a highway in north west Mumbai, January 3, 2018.

Mumbai came to a near standstill after a bandh was called to protest the violence at the event to mark the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon.

Photograph: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

While Vemula's death served as an important turning point for Dalit students, the conversation has only just begun.

The same sweeping statements are made when the privileged classes speak of Dalits who transcended poverty and became successful businessmen.

"But do they even recognise how we got here? Few understand that it is still a small fraction of Dalit entrepreneurs who make it big, while a majority of us are still struggling," says N K Chandan, director, Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

"The government has mandated that 4 per cent of all its purchases should come from Dalit businesses. But that number is never fully achieved."

Chandan, a businessman himself, points to a subtle change in attitudes if someone discovers that the businessman they’re dealing with belongs to a lower caste.

"They will never spell it out, but you'll suddenly find your payments getting delayed. This essentially makes several small businesses unviable. It is a quiet prejudice that still exists."

While announcing the Stand-Up India scheme in 2016, one that was to ensure easier loans for Dalits and women, Prime Minister Narendra D Modi had said, 'This scheme is going to transform the lives of Dalit and tribal communities.'

"But so far, only a handful of loans have been disbursed and the average size of each loan is a mere Rs 1.6 million," says Chandan.

It is for this reason that institutions such as DICCI become important, by not only providing a platform to collaborate, but also by offering a sense of a business community to men and women who have been treated like outsiders and untouchables all their lives.

"It is simply about instilling confidence, by offering a sense of brotherhood to overcome social prejudice," he says.

Dalit Enterprise, a business magazine dedicated to the community, is a step in this direction.

Though the law is supposed to be neutral, getting justice, too, can often prove to be a humiliating battle for the Dalit community.

IMAGE: During the Bharat Bandh, protesters block the Delhi-Gurugram Expressway, Gurugram, Haryana, April 2, 2018. Photograph: PTI Photo

Villages in Haryana are still fighting for a right that is often taken for granted: To walk into a police station and file a First Information Report.

"It is very hard to get the police to file a report against someone from an upper caste," says Rajat Kalsan, a Hisar-based Dalit lawyer and an activist with the Human Rights Law Network.

"Things are so bad that sometimes we have to sit on a dharna with the body of a Dalit victim to get the police to file a complaint."

There appears to be a silver lining, albeit on the somewhat distant horizon.

"On social media, the youth is getting increasingly involved in discussions on Ambedkar's teachings about equality. There are now Dalit activists being born even in the most remote parts of villages," says Kalsan.

Take, for instance, the genre of 'Chamar Pop'.

In Punjab and Haryana, young singers such as Ginni Mahi are calling out caste biases through folk melodies.

Mahi, something of a teen sensation in Punjab, travels across the world spreading the message of Guru Ravidas, the spiritual leader who the Punjabi Dalits follow as an alternative to other caste-based religions.

"The Mazhabi Sikhs, the lowest rung of the Dalits, took to Sikhism for its lack of inequalities. But unfortunately, the Dalits have been repeatedly let down by conventional religion," says Nirupama Dutt, journalist and author of The Ballad of Bant Singh: A Qissa of Courage.

IMAGE: During the Bharat Bandh, April 2, 2018, protesters hurl brickbats as smoke billows out of burning cars in Muzzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh. Photograph: PTI Photo

Where there have been figures such as Bant Singh and his daughter Baljit Kaur -- two strong voices emerging from among the Mazhabi Sikhs after Kaur was raped by upper caste men and Singh's limbs were chopped off because he took them to task -- the generation Mahi represents is one that is vibrant, aware of its rights and knows how to channel its anger through social media and other sophisticated tools.

This is perhaps also why leaders such as Mayawati -- one of their 'own' -- lost touch with the young, aspirational, Dalit and led to the near-decimation of the BSP in the UP assembly elections in 2017.

Mayawati's personality cult is also one that has harmed the Bahujan movement.

With Mayawati taking the central role, it meant her own caste, the Jatavs, received more attention.

This was the primary reason why other Dalit sub-castes began to look beyond the BSP and found their answer in the Bharatiya Janata Party, which, in turn, divided the community.

Lalji Prasad Nirmal, president of the Lucknow-based Ambedkar Mahasabh and a former aide and present critic of Mayawati, says her politics have caused irreparable damage to B R Ambedkar's mission and vision.

"Once she came to power, Mayawati, instead of trying to eradicate the caste system, made caste her agenda. The Dalit sub-castes are unlikely to return to the BSP fold any time soon," Nirmal says.

Her personality cult and the emergence of other young leaders have influenced how the Dalits in Uttar Pradesh vote.

"When established Dalit leaders do not allow a young crop of leaders to rise, a new and dynamic leadership was bound to emerge at the local level," Nirmal adds.

And yet, there is no coherent picture that emerges on a national level. The concerns of Dalits across states vary as their professions and immediate realities vary.

Sociologist Vidyut Joshi points out that the 'bunkars', or weavers, were one of the first communities to come to the cities with the advent of the textile mill and are now a three-generation-old urban community in Ahmedabad.

Their prosperity helped them lead change for other Dalit communities in Gujarat.

This is true for the 'chamars', or tanner community, of Punjab, which moved out of rural areas because it largely had skilled labour.

This is the sub-caste that has prospered, got its children educated and even sent them abroad.

The landless labour -- the Mazhabi Sikhs -- continues to suffer and fight battles that are different from the urban Dalit.

"Dalit was a new word in Punjab and came only with Kanshi Ram. It was a new identity. Their community finally had a respectable name, one that bound them together," explains Dutt.

A single identity, though, is still a distant dream.

Bant Singh and his daughter stand for change that is different from what their brethren in the cities want, or what students at HCU want.

And this, in turn, is starkly different from the struggling entrepreneur pleading for a loan.

Across factions, cities and villages, the Dalit struggle continues. But a sense of community, pride and kinship is gradually equipping them with the confidence and new tools to fight back bias.

Virendra Singh Rawat and Sohini Das contributed to this report.