| « Back to article | Print this article |

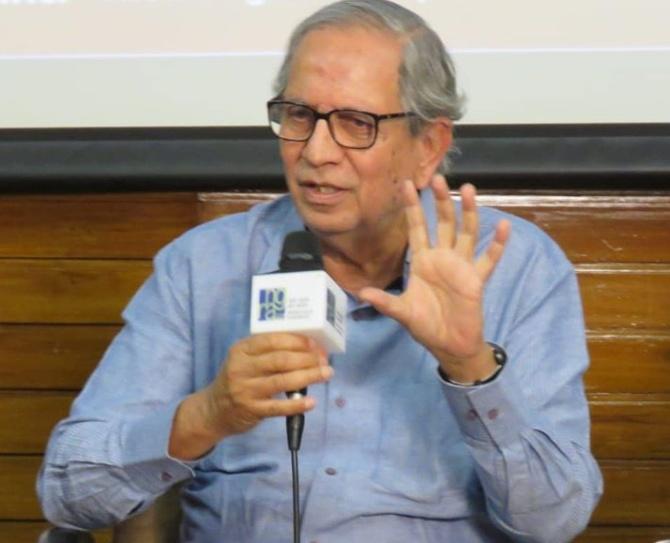

It is impossible for Mumbaikars not to glimpse themselves or someone they know in Sudhir Patwardhan's paintings, notes Ranjita Ganesan.

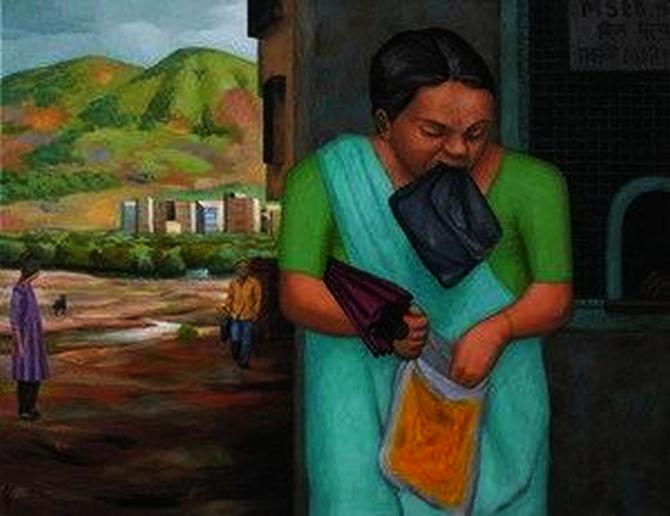

In Sudhir Patwardhan's Paying the Bill (2005), a woman stands stoically at the counter of the Maharashtra State Electricity Board office, umbrella tucked under one arm and her mouth gripping a purse so that her hands are free to rummage in a plastic bag.

She is likely searching for the bill. Just hours before seeing this work at the retrospective of the artist at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Mumbai, I had hiked to one such ramshackle office myself, to pay dues that wouldn't go through on the Internet.

It is impossible for Mumbaikars not to glimpse themselves or someone they know in Patwardhan's oeuvre.

It is as if he was there, observing as you went about the ungainly performance of everyday tasks, and chronicling on canvas the many ways in which people sweat the small stuff.

He had arrived in the city back in the mid-1970s, leaving behind a close-knit community in Pune.

"It was a culture shock, being suddenly exposed to this megacity where you are completely anonymous. The scale of the city and number of people in it also made a great impact," he recalls.

The city did not let him remain an onlooker. Taking up work, as a radiologist at the KEM Hospital, meant he was soon a participant in the city's choreographed chaos.

The traumatic yet deadpan navigation of buses, trains and autorickshaws, so often captured in his paintings, owes as much to observation as it does to his own daily experience in the early years.

"It is not like I was doing that in order to imbibe the city, I was living that life like so many others going to work."

The trains were not as crowded then, he says, and it was possible to sketch a lot.

He would draw versions of people he saw, sometimes even after they had got up and left. At home, he drew them from memory.

In later years, he took photographs of sites too. Every so often, he found one of the sketches could become a painting if he added references and developed its forms.

In his middle-class upbringing, there had not been a great deal of exposure to art.

But his father, who was talented in the crafts, dabbled in carpentry and neatly stencilled his name on trunks each time his transferrable job took him elsewhere.

From his mother, Patwardhan learned to enjoy reading. The painter in him only awakened while studying at Pune's Armed Forces Medical College.

There he was moved by books about Impressionist art, and began relating them to his own surroundings -- a sunny hostel in the city.

He also began reading to understand what it means to be an artist. Handling paint, cleaning brushes, painting, all seemed to come naturally to him.

It was in college that he was also exposed to Leftist thinking. For a young man living through a time of social unrest, with strikes in industry and the farm sector, it presented a way to understand these churns.

Though not one for active politics, Patwardhan remained engaged with the ideology. "I saw myself as a painter and not an activist. Representing the lives of the people, that was my work."

He made a series of works in 1977 documenting sensitively the labouring body and its exertion of muscle -- the unadorned, sari-clad Running Woman, the wearied labourer peeling off his vest in Construction Site, the worker hanging on an eponymous Truck, the waiter resting at a table in Irani Restaurant. These works are as much about the city as about the "tragic human species".

The piece de resistance of the retrospective curated by Nancy Adajania is Mumbai Proverbs, a wall-sized seven-panel mural made for the Mahindra family and which usually hangs in one of their corporate offices.

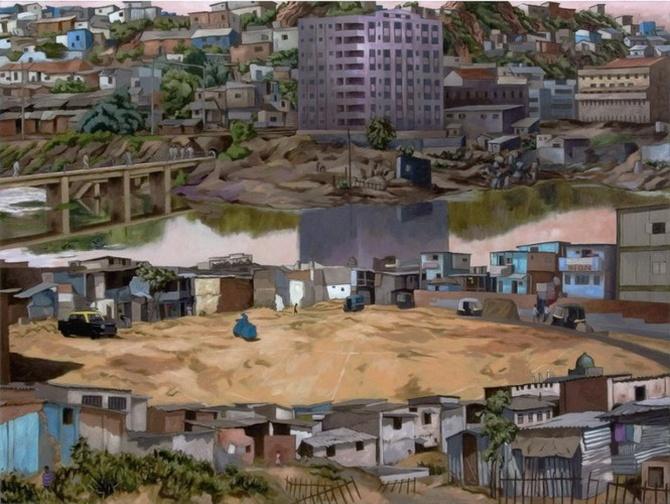

Here, like a partisan historian, Patwardhan records the city's development from its colonial architecture to the rise of industry.

He juxtaposes cubicles and cramped housing, luxurious highways and overcrowded streets.

States of flux have been a source of inspiration for him. In his Lower Parel (2002), for instance, the old railway footbridge, the tiny enterprises beneath, a closed-down mill in the background and the first of the skyscrapers co-exist, at once peaceably and turbulently.

He also captured the natural beauty of far-off Ulhasnagar (2001), being rapidly corrupted by effluents from its many industries.

In the 1980s, the artist had moved to Thane, where he later ran his own radiology practice until 2005.

This distant, verdant suburb, while on the periphery of the city, was still considered a small town then.

A deluge in 1991 submerged his ground-floor home and the paraphernalia of his art in several feet of water.

Patwardhan based a set of works on this moment -- Floods has a morose man bailing out water from his house, while another is seen wading with a television on his head in Man with TV.

He captured the atmosphere of unease created by the Bombay riots, when the artist felt a flicker of doubt about taking his usual route through Thane's Muslim neighbourhood of Rabodi, in the lowered gaze of the subjects in Shaque (1998).

One of his preoccupations has been to get those who are not normally associated with art involved with art.

So he painted a series titled Pokharan, an area in Thane, and exhibited it to residents there.

As the artist, now 71, ages and uses public transport less frequently, there is more of the indoors in his recent work.

Some of it signals stillness, some a sense of melancholic joy. His own family, particularly his wife Shanta, appears in several of the paintings.

Take Transmigrations, in which he reflects on home in various contexts on a single canvas.

His ancestral home in Sangli merges with the Pune house where his brother stayed which melds into Chicago where his son Tanmay lives.

Patwardhan says the artist's response to violent times should be to identify the capacity for harm within himself.

A pile of corpses is on a table in Inner Room (2017), where a man, woman and child are in a warped house.

The destruction raging outside their windows is evident in their own home too.

He notes that in any group of people, even during times of strife, there is a kind of rhythm that connects them.

When he painted Killing in 2007, he depicted a violent stabbing where the victim and killer end up in an intimate dance-like embrace.

He quotes in this context Carl Sagan's description in Pale Blue Dot of an image of the Earth taken from very far away.

'Every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there,' the astronomer wrote.

"In art, we must hold things together so that one understands something beyond violence is possible," Patwardhan concludes, "That we are actually one."

Photographs: Kind courtesy sudhirpatwardhan.com