| « Back to article | Print this article |

Shashi Tharoor says the British Museum should change its name to Chor Bazaar because whatever it has within its portals is the result of 200 years of theft.

The museum is once again in the eye of a storm for the possession of a statue of a god Hindus, across the world, worship as the Supreme Being.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports.

Lord Harihara made his divine debut on Twitter the other day.

Considered the Supreme Being, he is also called Shankaranarayana. The deity represents Shiva and Vishnu equally, being a vertical fused likeness of them both.

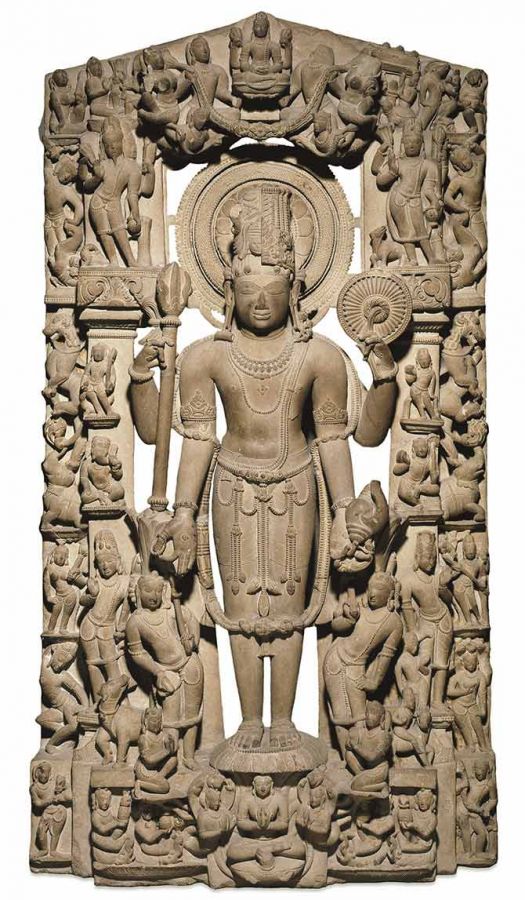

One of the most richly-carved and magnificent statues of Harihara was once situated, 1,000 years ago, on the exterior of a temple in Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh.

It is now located at the British Museum, London, 7,000 km plus away.

The British Museum routinely tweets, to the public, news on its best pieces. Probably to attract visitors or reawakening interest in history. On June 16 it did so about this Harihara along with a picture of the sandstone beauty.

The reactions to the god's appearance on the social media site were mixed.

Most were explosive.

Tosh_Tiwari: Hi Dear @britishmuseum, Are you hosting the world's biggest Live Crime Scene?? Showcasing looted Artefacts under one roof? How did this 1000 year old statue of "Lord HariHara" reach you? Would U care to explain to this nobody from Africa?

vinay3005: britishmuseum Time to return HariHara to their original abode in India. These are national treasures of India and belongs to its people.

artist_rama: Don't you feel it's time to return it's Heritage back to India. We Indians worship HariHara. Give it back to us. It looks so lifeless there with you.

thevijaymahajan: britishmuseum the right thing for you to do would be to return this and other Indian artifacts looted during colonial times to India (along with an apology). You should feel free to make a replica for display purposes. And yes, you are welcome.

rag_anand: Of course, with your silence, you are supporting the mistakes of what your forefathers did, aren't you??? Isn't that blood money which helped you educate? Which helps your facilities??

CheriChe: A post from SushmaJansari on a new Harihara at the @britishmuseum reminded me of this 8th c. Harihara, at Osian, Rajasthan. It's in a temple complex that has stunning figures, but is neglected and is now a car park for pilgrims to the more well-known shrines.

eddieduggan: Why stop there? The logic of your comment suggests all museums should "give back" everything in their collections! Should the great world museums "give back" global heritage items to ISIS for destruction? "Return" items to long dead cultures? Or preserve treasures for the world?

The hitherto relatively unknown existence of this glorious but precious effigy of Harihara -- one half of whom sports a trishul and the other half a conch and a chakra -- started up the next chapter of a nearly century-old debate over the correct place for the collective historical treasure of world museums.

Are museums duty bound to give back items pillaged from a country during the course of history, either through invasions or colonial rule?

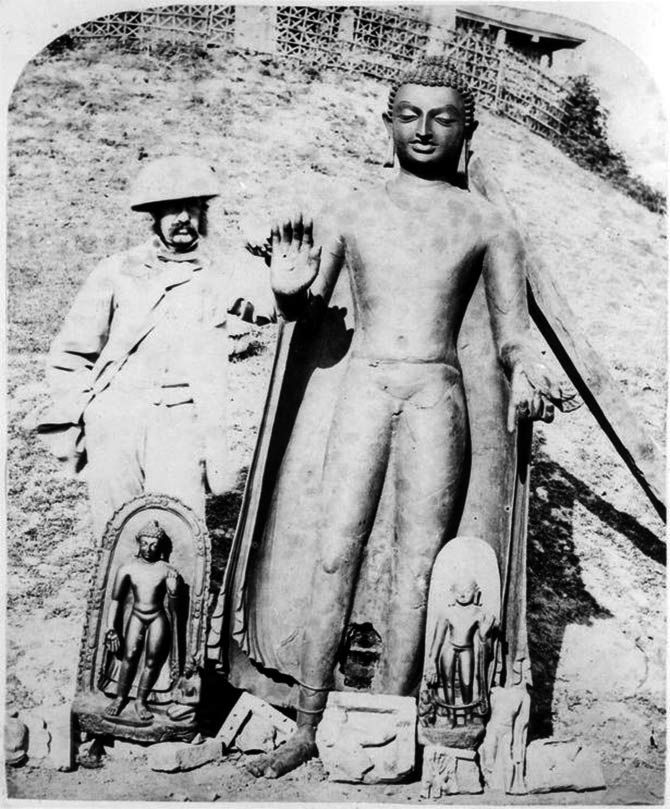

Should the majestic Koh-i-noor and the imposing Sultanganj Buddha go back to India?

And the breathtaking Elgin Marbles to Greece? The Benin Bronzes to Nigeria? The Rosetta Stone home to Egypt?

Does the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, have the ethical consent to display its collection of Kushan sculpture including the 3rd-5th century Fasting Buddha Shakyamuni?

Or the British Museum the right to show off the Amravati Marbles and the almost invincible Sikh king, Ranjit Singh's golden throne?

Can the Berlin Neues Museum continue to charge € 12 per head for tickets for viewing the stolen 3,500-year-old bust of Queen Nefertiti of Egypt?

Is giving back artefacts an essential part of improving nation-to-nation relationships?

Should history be rewound?

Should historical collections in museums even exist?

Every Indian, or person of Indian origin, who visits the British Museum and any other museums around the world, enjoys seeing the range of historical artifacts in one go. It offers a wide perspective on global history.

At the same time, how can one not feel a twinge of anger passing a showcase displaying a lovely Indian treasure?

Vijay Kumar is adamant in his view.

"They (historical relics) have lived over 100 years serving their colonial masters, who claim to have bought some (pieces) in open auction or others, like the Danes, say they paid locals a bag of rice or a pair of spectacles for the (12th century) Tranquebar bronzes (located in the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen)."

"It's time the gods come back home," he says. Vijay Kumar, or VJ, as he calls himself, who works in Singapore in shipping, also brings awareness blogging dedicatedly for a special cause.

He researches the ongoing illicit artifacts trade, tracking thefts of gods from Indian temples and the continuing thievery of priceless treasures from our historical sites.

But the 'mistakes' or U-turns/zig-zags of history may not be so easy to rectify.

On one hand. returning all historically misappropriated artifacts might open a messy Pandora's box, that could have even give the comely Pandora a nightmare.

It would be in all likelihood an enormous, expensive process, that is neither very feasible nor necessarily the kindest thing for the artefact.

<p">Also as nations don't we have so many more important concerns?

Says Michael Liversidge, emeritus dean, department of history of arts, University of Bristol, "My own view is that there are some things which are simply not negotiable -- objects which have a special significance because they are central to a belief, ancestral human remains which are integral to a society's culture, these are now generally accepted as belonging to where they originated, and many have been returned."

But he also points out: "Let's not forget that some of them have survived because they were collected long ago for study. If they hadn't been collected and cared for, they might not exist today."

"Other things -- art, antiquities and the like -- are part of a greater human archive: A lot of them were acquired long ago when these issues weren't debated as they are now, and many were legitimately collected at the time," Liversidge adds. "I think what we need to do first is to reconsider their history, then respond accordingly on a case by case basis."

On the other hand, many a nationalist Indian is of the view that Britain is duty bound to give back what it plundered.

Why?

For that simple reason: It was plundered.

No matter how difficult or cumbersome the process, they feel India should make a claim and stridently demand its relics back because it is a matter of national pride.

COMING NEXT: Will India ever get its treasures back?

Find out in the next part of Vaihayasi Pande Daniel's special report.