| « Back to article | Print this article |

Kausik Bandyopadhyay’s fascinating book, Mahatma On The Pitch, explores the relationship between the Father of the Nation and the Game that India Loves.

On the occasion of Gandhiji’s birthday, Rediff.com presents an excerpt from the book that shows how Gandhi changed the face of cricket as it was played then.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com.

With the onset of the Second World War, international cricket came to a standstill.

India’s forthcoming international ventures -- MCC’s tour of India in 1939–40 and India’s scheduled tour of England in 1940 -- got cancelled as a result.

However, domestic cricket including the Pentangular and the Ranji Trophy continued to be played in right royal earnestness.

The staging of the Pentangular, in that context, was to excite vehement debates about the advisability of organising the tournament in such a tense socio-political situation.

Thus, as the Pentangular season was approaching in 1940, debates on whether to hold it or not were on top. Arguments in favour and against the Pentangular poured in and flooded the newspapers.

The Muslim captain, Wazir Ali, supporting the Pentangular, declared: ‘I fully believe that the Pentangular is not, in the least, anti-National and will, and must, go on in the interests of Indian cricket. … every match that I have played in or watched has been played in an atmosphere of perfect sportsmanship and amity.’

K S Duleep Sinhji, on the other hand, considered ‘inter-communal cricket an unfavourable influence on the whole’ and ‘asked cricket fans to follow and support the Ranji Trophy’.

* * *

Furthermore, Gandhi’s opinion was invoked to justify the continuance of the tournament (The Bombay Sentinel, in its column ‘What the People Say’):

‘The latest cry is that the tournament should not be held this year because Congress has launched Satyagraha.

‘Till very recently Gandhiji was saying that the country is not ripe for Satyagraha. Even thereafter he is not for mass action.

‘Gandhiji himself knows that the people at large, not to speak of a large section of Congressmen themselves, are not so much in support of the ways of the Congress today as they were during the last Satyagraha movement.

‘It is therefore absurd to try to force abandonment of Pentangular when almost everything has been arranged to conduct the tournament.’

* * *

The Bombay Pentangular Tournament Committee announced the final schedule of the competition on December 5, 1940, with the hope of accommodating the Hindus in it.

The managing committee of the Hindu Gymkhana called an emergency meeting of its members on December 13, the day before the scheduled start of the tournament to consider the proposed withdrawal from the tournament.

Thus, while other gymkhanas were fully in support for the continuance of the Pentangular, the Hindus were in deep strife over the issue.

Ramachandra Guha nicely captures this dilemma: ‘It was the Hindus of Bombay who were caught in a bind. Placed against their undoubted love of the Pentangular were the insistent claims of Congress nationalism. With their leaders in jail, and given the insolence with which the Viceroy had treated their offer of conditional cooperation, could they turn up this year at cricket?’

* * *

The Pentangular debate reached a point of crisis in the first week of December 1940.

The top brass of the Hindu Gymkhana knew that its emergency meeting would not resolve the matter easily with so much of divergence and bitterness already rampant in the rank and file of the Gymkhana.

Hence, they preferred to seek the counsel of Mahatma Gandhi on the matter to resolve the impasse.

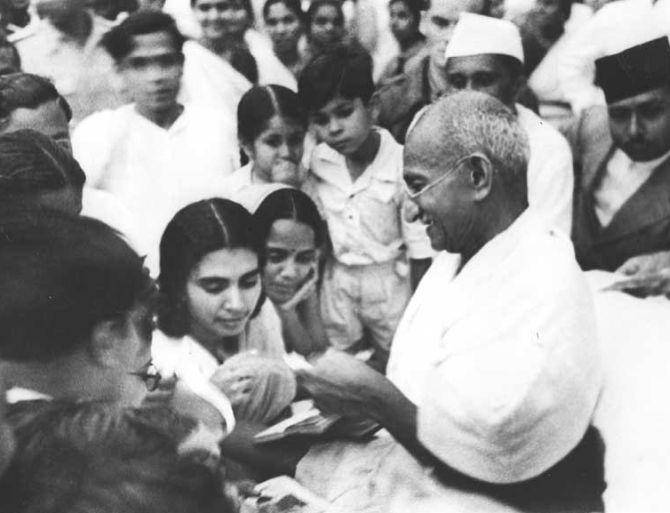

A three-member delegation of the Hindu Gymkhana comprising its president, S A Shete; vice-president, M M Amersey; and one member of the managing committee, Jamnadas Pitambar, met Gandhi at his Wardha ashram on December 6, 1940, and sought his advice.

Mahatma’s verdict on cricket

Once the ball was in the court of Gandhi, the Mahatma had to either play it or duck it.

Being an astute politician, the Mahatma decided to play the ball with a straight bat and tried to produce a politically correct straight drive.

His verdict on the Pentangular cricket, aptly described as ‘his most direct, considerate and consequential intervention in the world of cricket’, deserves reproduction in full:

‘Numerous inquiries have been made as to my opinion on the proposed Pentangular Cricket Match in Bombay advertised to be played on the 14th.

‘I have just been made aware of the movement to withdraw from the match, I understand, as a mark of grief over the arrests and imprisonment of satyagrahis, more especially, the recent arrests of leaders.

‘A deputation of three representatives of the Hindu Gymkhana have also just been consulting me as to what their attitude should be.

“I must confess ignorance of these matches and of the ‘etiquette’ governing them. My opinion must, therefore, be taken as of a layman knowing nothing of such sports and special rules governing them.

‘But I must confess my sympathies wholly with those who would like to see these matches stopped.

‘I express this opinion not merely as a satyagrahi desirous of getting public support in some way or other for the movement. I must say at once that the present movement is wholly independent of such demonstrations or adventitious support.

‘But I would discountenance such amusements at a time when the whole of the thinking world should be mourning over a war that is threatening the stable life of Europe and its civilisation and which bids fare to overwhelm Asia.

‘I would rather that all those who are blessed with intelligence and opportunity devoted both to devising means of stopping what appears to be senseless slaughter. It is like an ill wind which blows nobody any good.

‘And holding this view, I naturally welcome the movement for stopping the forthcoming match from the narrow standpoint I have mentioned above.

‘Incidentally I would like the public of Bombay to revise their sporting code and erase from it communal matches.

‘Incidentally I would like the public of Bombay to revise their sporting code and erase from it communal matches.

‘I can understand matches between colleges and institutions, but I never understood reasons for having Hindu, Parsi, Muslim and other communal Elevens.

‘I should have thought that such unsportsmanlike divisions would be considered taboos in sporting language and sporting manners. Can we not have some field of life which cannot be touched by the communal spirit?

‘I should like, therefore, those who have anything to do with this movement to stop the match broaden the issue and take the opportunity of considering it from the highest standpoint and decide once for all upon banishing communal taints from the sporting world and also deciding upon banishing these sports from our life whilst the blood-bath is going on.

‘I state this in fear and trembling and with apologies to Mr Bernard Shaw and others who think that a nation’s amusements most not be interrupted even while its flower of manhood is being done to death and is engaged in doing others to death and in destroying the noblest monuments of human effort.’

This statement was followed by another small dictum when Bhalerao, the secretary of the Bombay Hindu Cricket Club, in a telegram dated December 11, 1940, asked Gandhi ‘whether he wanted only Hindus to boycott the Pentangular cricket matches’.

Gandhi replied categorically: ‘ALL WHO HOLD MY OPINION MUST REFRAIN WHETHER FEW OR MANY.’

Even before Gandhi met the Hindu Gymkhana representatives, one BPCC member, who seemed to be in touch with Wardha regarding the matter, understood that Gandhi was ‘acquainted with the nature of public feeling in the city regarding the tournament’.

It was therefore predicted, ‘The news from Wardha is likely to lead to sensational developments. It is probable that the Hindu Gymkhana will withdraw their team from the Pentangular, which means Bombay’s annual cricket festival will be shorn of all its glory.’

Gandhi sounded categorical in his support to shun the Pentangular at a politically turbulent time affecting public life in India and the whole world.

This was in line with what Gandhi suggested in Hind Swaraj more than three decades earlier.

An Indian of real strength, he argued, ‘will understand that at the time of mourning, there can be no indulgence’.

But his incidental comment on erasing communal code from cricket alias sport was a reflection of his uncompromising stand on the question of communal amity in India.

Gandhi’s political stroke thus amply reflected the politicisation of sport as well. Guha aptly remarks:

‘The Mahatma’s credo was Hindu-Muslim unity: he had fought for it, and he was to die for it.

'Hindu-Muslim unity necessarily meant the unity of India.

'Did not the existence of a tournament on lines of community then undermine the idea of an inclusive nationalism? For if the Muslims were allowed a separate cricket team, what was to stop them demanding a separate nation?

‘What could Gandhi have done otherwise in playing the ball?

‘Even from a perspective of political advisability, Gandhi was reluctant to appreciate the element of ‘change of heart’ in cricket, which he so fervently advocated throughout his life.

‘If he could appreciate the game’s role in fostering communal amity in the years preceding 1940 through the Pentangular, he would have taken the chance to encourage the show to go on to cultivate the already enriched field of social unity vis- a-vis the communal face of politics and point out if Hindus and Muslims could remain in peace and brotherhood on the cricket field despite virulent rivalry, why could they not be able to remain so in politics and society, keeping India united?

‘However, in a tense socio-political situation, Gandhi, going by his political instinct, deemed that to be too risky a proposition.

‘Or may be Gandhi’s rigidity about the ideal of satyagraha and his aversion to modern codes of leisure stood in the way of experimenting with cricket as a cultural tool to foster communal amity.’

Excerpted from Mahatma On the Pitch: Gandhi And Cricket In India by Kausik Bandyopadhyay, with the kind permission of the publishers, Rupa Publications India Pvt Ltd.