| « Back to article | Print this article |

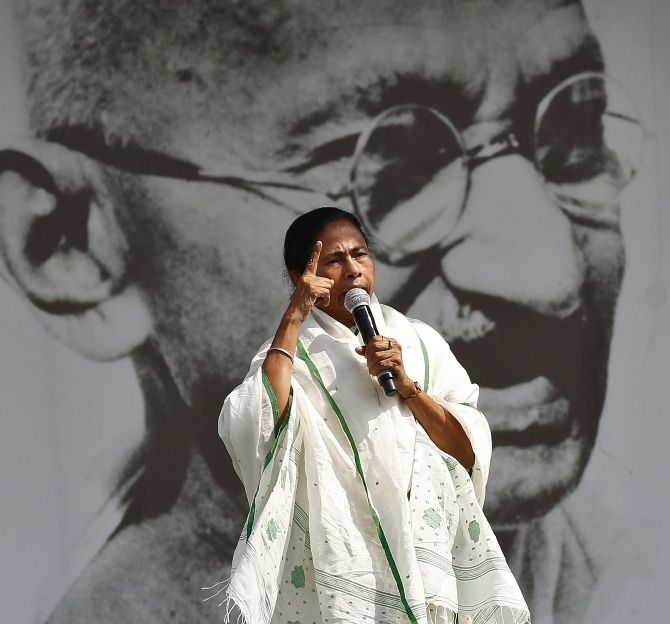

With her trademark cotton sari and rubber slippers and her generous doles in rural Bengal, many describe Mamata Banerjee as "ultra left."

Payal Mohanka reports on how Mamata hijacked the Left plank.

As West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee prepares to occupy her spacious 14th floor chamber with its panoramic view of Kolkata in the Nabanna building, the state government headquarters across the Hooghly, leaders of the Left Front introspect. Helplessly, they watch their mantra hijacked as the state prepares for the swearing-in on May 27 of "the more Left than the Left" chief minister.

Analysts crunch numbers and dissect the verdict: Trinamool Congress: 211 out of 294, the Left Front-Congress combine: 77, the Bharatiya Janata Party: 3, Others: 3.

In West Bengal, the Left's vote has dropped from 41% in the 2011 assembly polls to 26.1% in 2016. The main loser of this election is the Communist Party of India-Marxist, which lost a third of its voters compared with 2011.

The unkindest cut for a party which ruled the state for 34 continuous years is the fact that the Communists did worse than their ally, the Congress, thus relegated to third place in West Bengal.

Did the Left go wrong? Or did Didi, the common man's chief minister, just hijack its plank with her 'ma mati manush' mantra?

With her trademark cotton sari and rubber slippers and her generous doles in rural Bengal, many describe Mamata, as "ultra left."

In 2008 after the Left Front withdrew support to Dr Manmohan Singh's government over the India-US nuclear deal the Congress and TMC came together.

"Singur and Nandigram," says a political observer, "were incidental. The more significant factor was that a chunk of the ideology-driven grass-root level members of the Left Front migrated to the TMC. Ideology slowly made way for money, position and power."

Gradually, the Left saw its percentage of votes reducing. In a bid for survival, it realised that it had to join forces with the Congress.

While the Communists lost touch with the masses, which was their USP, Mamata began making successful inroads into their bastion.

She marched into districts and established a direct connect with the masses.

"This turned out to be an effective management tool. Greater accessibility and over a hundred meetings in the districts to monitor activity across different sectors have made administration easier," says an official who has attended many such meetings in the districts.

The CPI-M's well-oiled party machinery was its greatest asset. It was not just a popular mandate that had ensured its return to power for over three decades. Today, the funds are drying up and it has no source of income to support its machinery.

"In a large number of polling booths in the recent elections," a bureaucrat points out, "a number of Left candidates did not have polling agents in the booths."

Has the Left lost its relevance then in West Bengal?

"I studied the Soviet constitution in college in the mid-eighties," says a civil servant. "I went back to college in 1996 to meet my old professors. Interestingly, though the Soviet Union broke up in 1989, the college was still teaching the Soviet constitution as part of the paper on comparative constitutions. This is symptomatic of the problems of the Left."

Those who worked in the Left regimes recall how difficult it was to convince even the most pragmatic, solution-oriented Left leader when it came to issues regarding industry.

"I could not convince him that heavy industries was not the way forward for a densely populated state such as West Bengal with its very fertile soil and that we should go into services," recalls one bureaucrat. "The response I got left me helpless, 'No no, we have done what we wanted to do in the primary sector, now we can't go straight to the tertiary sector, we have to go to the secondary sector.' That didn't make sense to me because there are entire countries such as Ireland and Denmark that are relying on the tertiary sector."

The same officer finds the Mamata regime less rigid, more flexible and adaptable.

Civil servants under the Left were bound by rules making the system slow and bureaucratic. Rules were sacrosanct.

"Paradoxically, this government is far less bureaucratic, bureaucrats have far more freedom," he adds.

Mamata's critics say she does not hesitate to break a rule if it is a hurdle in her path. While speed of delivery has improved, so has her image grown as an autocratic administrator with scant respect for rules.

Moving with the times, Mamata is wooing business and investment in the state.

In 2003 the Left Front government's premium PSU for the development of industry in Bengal had made good profits. Eager to make an announcement, the team approached their chairman. His first reaction left them speechless: 'A government entity making money, will that be right to announce?'

Business and money were unholy words in that era.

"Mamata is definitely not elitist. But neither does she have the earlier hang-up that it should look poor, so the poor can identify with it. Without a doubt, she is populist, but not necessarily in a pejorative way, explains a bureaucrat.

Political observers in the state feel it is wrong to flog the Left for combining with the Congress for this assembly election. It was the only route available to the Left. Had it gone alone, the BJP, which won 10.2% of the votes this election, would have made even deeper inroads in the state.

At the same time, the jot (alliance) came too late and without a common agenda and ideology. "The Rahul Gandhi-Buddhadev Bhattacharya camaraderie could not get translated at the block level," says a senior government officer. "They needed to come together two years before the elections. This hurriedly stitched jot was a still-born child."

IMAGE: West Bengal Chief Minister and Trinamool Congress chief Mamata Banerjee addresses a rally. Photograph: Anindito Mukherjee/Reuters