| « Back to article | Print this article |

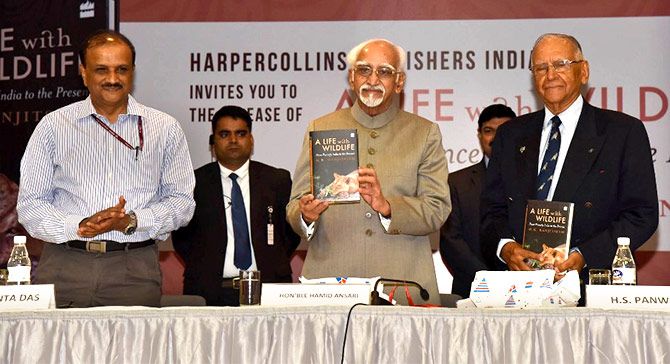

'A Life With Wildlife is a must for all who are concerned about how a billion Indians will coexist with over 500 mammals and 1,300 birds, not to mention 25,000 flowering plant species in the new century,' says Mahesh Rangarajan.

Readable memoirs by Indian civil servants are few and far between.

The legendary R P (Ronnie) Noronha of the Indian Civil Service penned the classic A Tale Told By An Idiot, which concludes in the late 1960s.

B K Nehru, with his long distinguished career as bureaucrat, diplomat and governor, penned an inappropriately titled but charming book called Nice Guys Finish Second.

These gave rare insight into the goings-on at the district and state levels and at the apex of the political pyramid.

A Life With Wildlife is a different kind of memoir.

It is as much about the passion as about the man himself.

Why a student of masters in history from Delhi's elite St Stephens College and an Indian Administrative Service officer of the 1961 cadre should be so dedicated to the denizens of the forest may be a mystery at first sight.

M K Ranjitsinh's work shows how the world in which he grew up, princely Wankaner, a state-let in Gujarat, was one where skeins of geese darkened the sky in winter and it could take hours to cross a road due to large herds of black buck.

Having watched these birds and beasts first through the sights of a rifle, for he was an avid shikari, he later became an ardent conservationist.

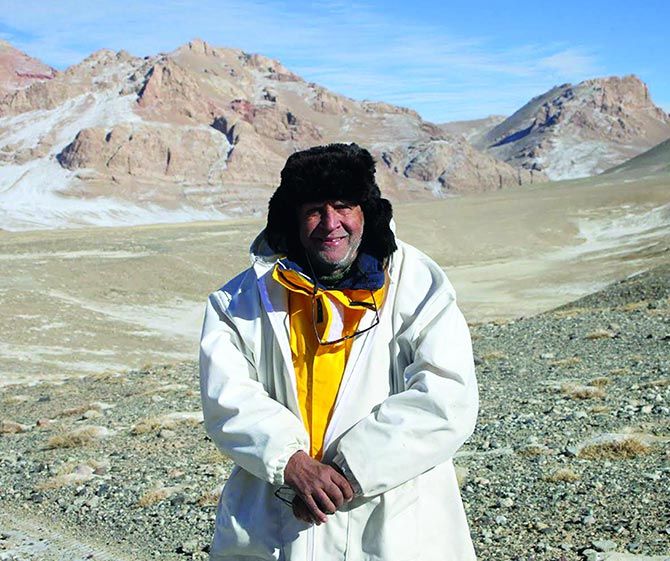

This, then, is the story of his journey through life, which has taken him to a host of wild and beautiful places.

Stunning colour photographs of Indian animals and birds as well as many from remote Asian landscapes grace the book.

But the core of the story is as riveting and relevant as those who wrote of the corridors of power.

Ranjitsinh argues strongly in favour of a second look at the princely legacy.

As many as 277 of India's parks and sanctuaries, more than one in three, began as a hunting reserve of the princes.

He shows how some, like the Nawab of Junagadh, took care to protect the rare lions; others, like his older relative in Dungarpur, reintroduced the tiger once extinct in the forested hills of the state.

Such legacies crumbled after Independence.

Even as he looks back to the days of duck shoots and falconry, beats for tigers and long waits in machaans, he does much more.

He asks why independent India took a good two decades to get an active machinery in place to save its wild heritage.

His own life shows up part of the answer.

As a young civil servant he joined forces with forest officials to help secure and protect better the forests and maidans of the Kanha Park in central India, giving a lease of life to not only the tiger but the central Indian barasingha (stag).

This slow maturing of awareness of the many ways in which humans were obliterating the natural world found a champion at the pyramid of power: Indira Gandhi.

The author was in the right place at the right time as director, wildlife preservation and found the federal government in the early 1970s seized with decisive energy to protect forests, wildlife and nature.

His recounting shows directives and decisions from the very top, powering the creation of reserves and all-important laws on forests and wildlife.

It is fascinating that on his return to the state cadre in Madhya Pradesh, he drew on the same laws and helped vastly expand the acreage of protected areas.

Along the way Ranjitsinh earned a doctorate on the black buck antelope, but the main thrust of the latter half of the book is not celebration but critique.

For one, he sees in successive governments a weakening of resolve and a lack of appreciation for the wider role of ecosystems for human welfare.

Short-term gain for economic growth is matched by populist demands for land for cultivation and livelihood.

To be fair, since his retirement in 1996. he has been a key figure in voluntary efforts including innovative schemes to compensate cattle-owners for livestock losses to tigers.

He also advocates community-level conservation and does not mince words about government indifference to the under classes as much as to nature.

Yet, at the end is a nagging question.

If nature to be secured requires power from the top to flow in the desired direction, what when that resolve weakens?

If anything, the high tides of rapid unplanned growth in democratic India as much as in authoritarian China will not leave much space for nature.

Securing a wider constituency may need much more than good enforcement and a hard, tough government.

It may call for a different set of approaches that go beyond the State and into society for succour and support.

The book does, however, demonstrate an exceptional memory, often stretching back decades.

Encounters with animals and wild places have rarely covered such a spectrum of habitats and landscapes.

There are also rare vignettes.

When the lion was about to make way for the tiger as India's national animal, the author argued in favour of keeping the former.

Karan Singh accused him of wanting the lion because it was part of his name and he was a Gujarati.

Ranjitsinh retorted that the latter's nick name was 'tiger'!

He lost this standoff, but seems to have stood his ground against a powerful environment minister, Bhajan Lal, in the 1980s on the far more important matter of easing environmental protection rules.

All in all, A Life With Wildlife is a deeply educative read and a must for all who are concerned about how a billion Indians will coexist with over 500 mammals and 1,300 birds not to mention 25,000 flowering plant species in the new century.

This is a fine account of one who tried and, though in his eighties, soldiers on.

The wild may or may not survive unscathed, but this is a fine account of a stout defender of its place on the planet.