Part I of the interview: 'Gandhi should never have agreed to Partition'

Homai Vyarawalla started her photographic career in Mumbai, the city where she moved to for further studies from her native Navsari in Gujarat. She earned a diploma in art at the prestigious Sir J J School of Arts.

Though she was attracted to painting, she realised soon enough that it would not bring much money. Photography was "something new, something interesting and artistic enough." Plus, it paid well -- she received Re 1 for each of her initial photographs, a good sum those days.

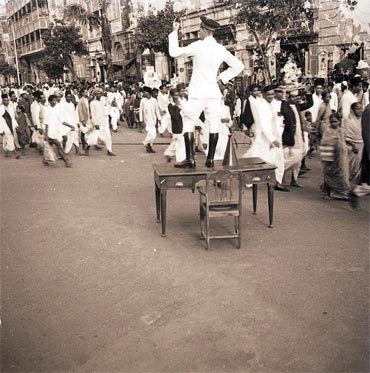

Vyarawalla's photographs of Mumbai -- taken in the late 1930s and early 1940s -- tell the story of a city that still managed to sleep at night, which gave its residents the time and space to catch a breath.

The photographs hark back to a time when the regal Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus was called Victoria Terminus, when traders waited on the streets to catch the sight of a good omen before starting their daily business, when people enjoyed a rain-washed afternoon at the Gateway of India.

Now 97, she misses the "serenity" of the old Mumbai -- the city where she and her husband had celebrated their marriage by having bhel puri at Girgaum Chowpatty on their wedding day.

Mumbai, she feels, "is too overcrowded. The traffic is overwhelmingly slow. There are far too many things for a smaller space. Earlier, the roads used to be washed. The city is no longer as nice and clean."

One of her photographs proves the adage that the more things change, the more they remain the same. It shows harrowed residents in then south Bombay traversing through knee-deep waters, and is not unlike the photographs that appear in newspapers when rains wash away parts of Mumbai each year.

She has not taken a single photograph in the last 41 years.

"It was not worth it any more," she says, lamenting the "bad behaviour" of the new generation of photographers.

"We had rules for photographers; we even followed a dress code. We treated each other with respect, like colleagues. But then, things changed for the worst. They (the new generation of photographers) were only interested in making a few quick bucks; I didn't want to be part of the crowd any more," she says.

Didn't she miss meeting Presidents and prime ministers, diplomats and bureaucrats? Vyarawalla shakes her head and states, "I thought I had done enough."

Homai Vyarawalla also refuses to sell any of her photographs, in spite of being offered extremely handsome prices for some of them.

Instead, she has handed over her entire life's work -- priceless photographs taken between 1937 and 1970 -- to the New Delhi-based Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.