Photographs: Ed Nachtrieb/ Reuters Claude Arpi

China too has gone through tremendous changes. The Middle Kingdom has become an economic power to reckon with; some even say that it will be the 21st century's superpower.

However, it is still suffering from a deep scar, the reigning party killed thousands of its own children on Tiananmen Square at dawn on June 4, 1989. Today, the regime in Beijing is not ready to admit to any wrong doing and even less to consider changes in its policies.

Young China believed that Democracy and Freedom could help their country to take its rightful place in the world, but the oligarchs in Zhongnanhai sent the tanks to smash thousands of striking students.

Ironically, it was not only the 'common man' or a few intellectuals who believed in the necessity for a greater involvement of the people in China's governance, many in the Communist Party thought that the time had come to evolve and drop the dictatorship of one party.

Every Chinese person, whether a party member or not, should be entitled to participate in the rise of China, thought the students. They paid dearly for their daring dreams.

How China has 'digested' the event 20 years later

Image: A protestor impersonates a student victim of the 1989 pro-democracy movement in Beijing, during a protest march in Hong Kong on May 31, 2009Photographs: Tyrone Siu/ Reuters

Some of his disciples were Zhao Ziyang, then the party general secretary, and Xi Zhongxun, the deputy chairman of the standing committee of the National People's Conference. It is a historic fact that in 1989, the politburo was divided into two factions when it came to the matter of 'democratic' reforms.

We have today a rather accurate picture of the split within the central leadership, especially after the minutes of the meetings held by the politburo members and the group of Elders headed by Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader, were smuggled out of China in 2001 (presumably by a participant of the May-June 1989 events in Beijing).

When Hu Yaobang passed away in April 1989, what history will always remember as the 'Tiananmen democracy movement' started to unfold.

The details of the 'incident,' as Beijing still terms it, are too well known to be recounted here, but it is worth looking at the way China has 'digested' the event twenty years later.

Hu Jintao is seven times less powerful than Mao

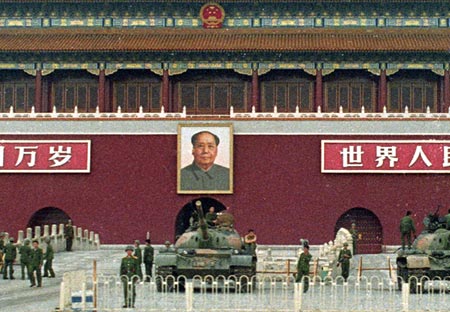

Image: The Chinese People's Liberation Army guards the Gate of Heavenly Peace and Chairman's Mao portait in Tiananmen Square on June 9, 1989Photographs: Richard Ellis/ Reuters

He affirmed that China will never, never implement a 'Western type' democratic system.

These words were pronounced two months ago during the annual session of the National People's Congress. Wu added: 'We can by no means indiscriminately copy the Western system.'

It was partly a response to the Charter 08 signed by hundreds of prominent Chinese intellectuals. The document stated in strong terms that political democratisation was a need for China.

The charter asked for sweeping changes to create a 'free, democratic and constitutional State.'

While the release of Charter 08 coincided with the 60th anniversary of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Wu's declaration was made to placate many Chinese deputies wanting to raise the issue during the National People's Congress.

Wu explained: 'China's system of political parties is a system of multi-party cooperation and political consultation under the leadership of the Communist Party of China, not a Western-style multi-party system.'

Wu is probably not aware that 'democracy' has not been invented by the West. More than 2,500 years ago, in the Buddha's time, small democratic republics flourished in North India; archeologists have even said that more than 5,000 years ago, the Indus-Saraswati civilisation knew the principle of decentralisation and participatory governance.

Greece and the West discovered it much later. It is therefore wrong to associate 'democracy' with the West.

The 'Fifth Modernisation' as the famous dissident Wei Jingsheng called it, is still taboo issue in Communist China, though many believe that it is just a pretext for the party to avoid relinquishing its dictatorship over the Chinese nation.

For the past 20 years, the Chinese leadership, at least the hard-line faction has stubbornly refused to follow the world trend towards greater transparency and enroll the participation of ordinary (non-party) masses in the governance of the nation.

The present leadership, despite its dictatorial attitude is rather powerless. A friend with great knowledge of the functioning of the party told me recently that President Hu Jintao is seven times less powerful than Mao.

I don't know how he arrived at this figure, but it is a well-known fact that today the party's leaders can't take any forward-looking decisions because of their divisions and lack of personal charisma.

20 years later in China, everything is done in the name of 'stability'

Image: Current Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao with Zhao Ziyang, his mentor, at Tiananmen Square, May 1989As Zhao assures the students that all issues could be dealt with 'in a proper manner,' Wen Jiabao, China's present prime minister, stands behind him. He was then the director of the general office of the CPC Central committee.

Take Xi Jianping, who is today Hu Jintao's heir apparent; his father Xi Zhongxun was one of the staunchest reformers and a close supporter of Hu Yaobang. Is it not an indication that in the party all may not share Wu's views?

Unable to reach a consensus, the hard-line always prevails. It has been the case, amongst others, for the negotiations with the Dalai Lama's representatives.

It is also what happened during the months preceding the Tiananmen massacre. As no consensus could emerge, the hard-liners (the Eight Elders lead by Deng Xiaoping) prevailed.

On June 6, 1989, two days after the tanks had rolled on the Square, a meeting of the Elders was held in Zongnanhai. Wang Zhen, the vice-president of the People's Republic and an old soldier stated:

'We're are still going to rely on the PLA to stabilise things. We need to get the PLA, the PAP (People's Armed Police) and the regular police all out there hitting those counter-revolutionary rioters as hard as they can, arresting when necessary, killing when they need to, and being absolutely sure no rioters get away.'

'Stability' became the leitmotiv. Twenty years later in the Middle Kingdom, everything is done in the name of 'stability,' a euphemism for one-party eternal rule.

A recent example has been the bloody repression of the Tibetans in March-April 2008. More than 200 Tibetans were killed on the high plateau during these two months, just because the Tibetan masses expressed their resentment against the Chinese cadres.

The same Chinese were supposed to have 'emancipated' and 'liberated' the common men and women of the Roof of the Word in 1950; they had entered Tibet with this only purpose.

Such a sad joke on the Tibetans! Twenty years after the Tiananmen massacre, more and more news of arrests and death condemnations are trickling out of Tibet.

China has been destabilised by the global economic crisis

Image: Chinese soldiers at the Great Hall of the People in BeijingPhotographs: Nikhil Lakshman

A commentator recently wrote in The South China Morning Post: 'So, after having been victimised by the forces of nature, they are now being victimised by agents of the state who monitor their every word and pressure them to accept their loss stoically; to put their faith in the Communist Party and the government.'

Examples could be multiplied. This comes at a time when China has been destabilised by the global economic crisis. Ian Campbell, wrote for breakingviews.com: 'The Chinese are worried that the decisions by the US and the UK to try to print their way out of economic trouble will end badly. The money creation could end up debauching the dollar and pound and inviting a global inflationary crisis.'

China has $744 bn of US Treasury bonds. Obviously if the dollar loses its value (or does not remain the reserve currency, the main loser will be China which will then face real destabilisation.

All this can only increase the paranoia of the present leaders. Like many CEOs the worlds over, they could loose their job as a side effect of the present crisis.

A Chinese friend recently argued with me, "One-party rule is better that your 40 party kitcheri in India." I could not defend the present Indian system, but I told him that even if a Middle Path might be ideal, at least in India we have a security valve and the possibility to throw out a corrupt or inefficient government. It makes a big difference and it ultimately assures a great stability, even in apparent chaos.

At a time when my ancestors the Gauls thought the sky risked falling on their heads, the Chinese Emperors already feared 'chaos.'

The question for the new emperors is will empowerment of the people bring chaos in China or help defuse it? Common sense indicates that the latter is most likely.

article