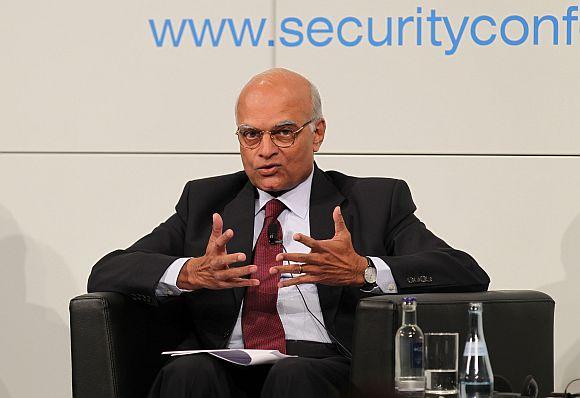

Photographs: Courtesy Munich Security Conference National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon

Global governance would be a good idea, but there is no imminent sign of it breaking out...

Neither India nor China is saying that conflict is inevitable as a result of the emergence of newer powers...

The so-called Arab Spring could actually be seen as the revenge or return of politics...

By no stretch of imagination can the UNSC be called democratic or representative...

National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon did not mince words during his speech on 'Rising Powers and Global Governance' at the Munich Security Conference on February 2. Here is what he said:

To begin with, I am not sure that the description "rising powers" fits those normally referred to in Western discourse by that term.

Many of the so-called rising powers think of themselves as actually restoring the historical norm in terms of the international hierarchy or distribution of power, or, in other words, as returning to a more normal order of things in the world.

In India, most of us choose to be more modest, describing our main task for a long time to come as our domestic development rather than any revisionist attempt to reorder the world.

"Emerging powers" or, better still, "re-emerging powers" may be a safer and slightly less condescending way to describe these powers.

...

'Neither India nor China say conflict is inevitable'

The Question: Is Conflict Inevitable?

The problem with emerging powers is largely in the minds of the established powers.

Because of the European historical experience over the last four centuries since Westphalia, when four out of five transitions of power from one dominant power to another has involved conflict, there is an assumption that the rest of the world will follow the same rules and that friction or even conflict may be inevitable as we move to a flatter distribution of power in the world.

The (Mixed) Answer

But both empirical experience and logic tell us that the readjustment can be smooth. In the last 20 years we have already seen breath-taking changes in the distribution of economic power in the world. These occurred peacefully and relatively smoothly.

Secondly, no emerging power is predicting the imminent decline of Western dominance.

Thirdly, the world is now an interdependent globalised world where political and military powers are no longer as closely or monopolistically held as in the past. Self-interest alone should ensure that friction is minimised.

If I understood Minister Song Tao (China's vice minister for foreign affairs, who too spoke at the Munich conference) correctly, neither India nor China are saying that conflict is inevitable as a result of the emergence of newer powers.

...

'By no stretch of imagination can UNSC be called democratic or representative'

Image: UN headquarters in New YorkIs global governance the answer?

I suppose it is natural that those who fear the readjustment in decision-making that should come with shifts in the distribution of power in the international community look to global governance to prevent it.

The fact is that the world today suffers from a deficit of global governance. In most areas, global governance is notable by its absence.

There is no shortage of international institutions with over 300 multilateral organisations in existence today. But their legitimacy is declining and effectiveness questionable.

By no stretch of imagination can the main multilateral institutions charged with responsibility for peace and security, like the UNSC, be called democratic or representative.

There is little evidence of global governance in the management of relations between major powers or in the handling of crises.

Take Libya, or Syria for that matter. The governance deficit may, in fact, be one reason why the consequences of intervention have been so different from what was promised and, I assume, expected by its sponsors.

...

'Arab Spring could actually be seen as the revenge or return of politics'

Image: File photo of a Libyan rebel fighter walking past a graffiti depicting Muammar Gaddafi at a checkpoint near Yafran in western LibyaPhotographs: Bob Strong/Reuters

We have also seen a progressive militarisation of international politics and of the instruments that some members of the international community apply to crises and problems.

The so-called Arab Spring could actually be seen as the revenge or return of politics.

I realise, of course, that established powers are not going to happily hand over or share power with re-emerging powers, unless essentially unpredictable events beyond their control in the global economy or politics make this in their self-interest.

To expect otherwise would be to expect too much, and to expect human nature to be held in abeyance.

Besides, none of the so-called rising powers is claiming the right to run the world or is laying down a new set of rules for global governance. None of them has described an alternative vision of the global order, or offered itself as "the city on the hill".

Their hierarchical or relativistic strategic cultures are non-proselytising and realist. Their expectations of others are low, and they have historically shown little inclination to improve, convert or democratise others.

This is partly also because the emerging powers have been the beneficiaries of aspects of the present international order, particularly economic integration and globalisation, and the use of the global commons.

Whether this will remain so in the future is an issue, when international peace and security is more challenged than it has been for a long time; where new patterns of global responses are called for in new domains of contention such as cyber space and outer space; and, where new economic initiatives are essential to address food and energy security.

...

'Global governance would be a good idea, but there is no imminent sign of it breaking out'

Image: The UN General Assembly session in progressSo I suppose that my short answer to the question implicit in our topic is that global governance would be a good idea, but that there is no imminent sign of it breaking out.

The emerging powers would certainly like improvements in the world and the way it is run, making it more democratic and responsive to the needs of the vast majority of those who inhabit this planet.

What we seek is reform in the way the world's issues are managed. I do not hear emerging powers calling for a revolution. (Presumably that would come if the emerging powers felt that the international system no longer responded to their needs of domestic development and transformation. That could actually vary from sector to sector.)

Rationally speaking, reform of global governance in itself should not worry any but the most dyed-in-the-wool reactionary or conservative power. Surely it is in our common interest to improve the way the international community conducts its affairs, strengthening purposeful multi-lateralism and international law.

What we might seek is not a utopian system-of-systems to manage the world or to mimic internal governance internationally. What we might try is building the habits, the institutions and the architecture to work together democratically in the international community.

Click on NEXT to go further...

article