| « Back to article | Print this article |

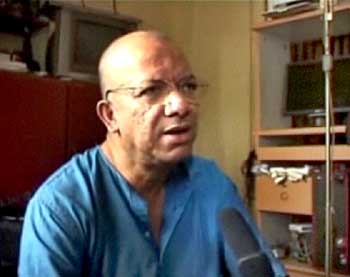

'Politics was never my cup of tea'

No stranger to controversies, Suman's latest CD Chhatradharer Gaan (Songs of Chhatradhar Mahato) created a furore, as many of the songs were openly sympathetic to the struggle of Bengal's tribals against the establishment.

Elected last year to the Lok Sabha as a Trinamool Congress candidate, he is in the news as much for his vociferous opposition to Operation Greenhunt as for his constant differences of opinion with party chief Mamata Banerjee.

The songsmith recently threatened to hold a protest outside Parliament against the operation launched to flush out Maoists. The first-time MP has claimed that these operations are against the interests of the tribals residing in Maoist-infested areas.

Suman has also offered to mediate between the Centre and the Maoists, after Maoist leader Koteshwar V Rao alias Kishenji named him, along with writer Arundhati Roy and former bureaucrat B D Sharma, as the intellectuals who could facilitate the dialogue process. Home Minister P Chidambaram has turned down Kishenji's offer, firmly stating that talks will take place only after the Maoists halt their violence.

In the first part of a free-wheeling interview rediff.com's Indrani Roy Mitra finds a singer madly in love with the language of music, and a politician who admits that politics is not his cup of tea.

How do you manage to do so many things at a time? What's the secret?

There is no secret, maybe I have a problem somewhere (laughs). The eminent psychologist Alfred Adler, who was a disciple of Sigmund Freud, once said that creative people suffer from an inferiority complex. Because of this inferiority complex, perhaps, people like me try to establish a few things. Adler, however, made this statement in all earnestness, and not the way I am putting it.

To be honest, I have been restless throughout my life, I have been regularly inconsistent. I have been consistent only with my friends and my music. I hopped from one job to another; never found peace.

I always tried to express myself in so many ways -- through music, through broadcast journalism, writing, conversations, people's movement and also through acting. Ironically, I never tried to express myself through politics. Politics was never my cup of tea.

'For me, inspiration lay in Ustad Amir Khan's khayal'

Music came naturally to me. My parents -- they are both dead -- Uma and Sudhindranath Chattopadhyay -- were reputed singers/musicians.

My father was more famous of the two. In the 1940s, he had at least 100 gramophone discs to his credit. My mother too had several discs and both sang for the radio. My father took up a job in All India Radio during the British Raj. It was Kazi Nazrul Islam, one of my father's mentors, who wanted him to join AIR.

It was the maestro himself who negotiated with AIR and made him (my father) join as a production assistant. My father being a man of strong principles, at once gave up singing in public.

I was born with music, you see. I heard before I saw. At home, I always heard my parents singing. However, no one tried to give me music lessons till I was 8.

At that age, my father started teaching me all kinds of Bengali songs. My parents had a very liberal attitude towards music. Anything that sounded good could be sung. I still remember my mother singing Khoya Khoya Chand by Mohammad Rafi while cooking. There was no so-called bourgeoisie policing at home. No one ever told me that a particular song was good and another was bad.

At 12, I started to take lessons in Hindustani classical music from Kalipada Das. I owe so much to him.

Later, I came in contact with Ustad Amir Khan. I could not become his direct disciple, though. For, Ustadji wanted to take me to Mumbai (then Bombay) with him. But my father did not allow me to give up studies.

Having tested the waters as a professional musician himself, my father did not want me to have the same career. Rather, he thought I should complete my graduation, have a regular job and pursue music as my first love.

At 17, I heard Amir Khan at a concert in Kolkata. And it changed my life. It radicalised me for good.

You mean Ustad Amir Khan's khayal radicalised you? How?

(Smiles) Yes. People read Che Guevara, Mao Zedong or Karl Marx and become radicals. But for me, inspiration lay in Ustad Amir Khan's khayal, his style and view of khayal, the way the maestro took the khayal form on.

Amir Khan's gharana radicalised me, even politically. By listening to him, I started to question myself. Once I heard him say, 'If you do riyaz for two hours, ask yourself for four hours -- what are you doing the riyaz for?' It was he who taught me to look into myself and seek an answer.

'I was forced to leave India'

Those were turbulent times. The Congress party's grip on Bengal was slackening and the Leftist forces were coming up. Bengal was reeling under the Naxalite movement.

Many people think you were involved with the Naxalites.

Strangely, yes. But I never had any inclination for politics. Frankly, I had no time. I had to do riyaz for 6 to 7 hours a day. I would get up early in the morning, do riyaz for 3 hours before leaving for college.

In 1966, at the age of 17, I already had a B High grade in music. Bengali music at that time was adorned with great names like Hemanta Mukherjee, Manabendra Mukherjee, Shyamal Mitra, Satinath Mukherjee, Tarun Banerjee. They were there like celestial bodies.

I cut my first two Rabindrasangeet discs in 1972 and 1973. I was an upcoming singer at 23, 24. Music ruled my life. When I took up a job, I got up at 5, did my riyaz for three hours, went to work and on return started my riyaz again.

I was so much in love with music at that time that my first marriage ended in divorce just like that (smiles). This corroborates the fact that I simply had no time for politics. However, I did have a political bend of mind. I was constantly asking myself -- what was I singing for?

And then by the mid-1970s, you stopped singing. Why?

I realised soon that the songs that I was singing were not satisfying me. They did not speak on my behalf. I felt I would have to write my own songs. I tried, tried hard but failed. It took me several years before I could find my voice.

Meanwhile, I had to leave India over a paltry issue, an infantile misunderstanding. The Emergency was coming. Some people were irked with me and my parents and those close to me were of the opinion that I might get arrested.

I was forced to leave India on May 12, 1975 for Germany and the Emergency was declared soon after.

'I was itching to sing my own songs'

Around that time, Voice of Germany had opened its Bengali service. While in Germany, I started learning the language and soon got a job in the Bengali division of Voice of Germany. My German was not that bad, you see. I became a radio journalist, a career that I pursued for over a decade.

From Germany, I went to the United States of America. I worked for the Voice of America in Washington, DC for some years before returning to the Voice of Germany again. My last assignment was that of a senior editor at the Bengali service of Voice of Germany.

I had started writing songs in Bengali and was itching all over to sing my own songs. I was 37 then. At that age, I started taking lessons in finger-style guitar from an Italian guru in Cologne. That changed me altogether.

Prior to this, I used to play the keyboard but I could not carry the keyboard with me. It was too heavy and I needed to learn a string instrument. First I thought of playing the dotara. But in dotara, one cannot play the chords. Hence, I opted for the guitar. I soon became some sort of a strummer. I could never become a guitarist -- it was not possible at that age.

Thereafter I told myself, 'Enough is enough, I must go back to Kolkata now and see what I can do with my songs.'

I could have stayed in Germany, the US, Japan or Holland or could have pursued my career as an international broadcast journalist but I did not. And that is how my career in music started.

'Urban Indian songs are like illuminated lemonade'

The answer lies in your question itself. It occurred to me that India is such a wonderful country with a plethora of songs and genres. Yet, the songs that we, urban Indians, produced were mostly love songs. They appeared rather boring to me. They were like illuminated lemonade.

Even today, most of the songs that Mumbai or Bengal produce, lyric-wise and structure-wise, are endlessly repetitive and infantile. This infantilism bothered me. Where is my statement, I asked myself.

Rabindranath Tagore did not offer me any respite, Kazi Nazrul Islam did not. Neither did Salil Chowdhury. I could not find my language there.

All my life, I have been looking for my language, my expression. I have always wanted to be myself. Hence, I decided to be shamelessly myself in my songs. And since I am situated amongst you and we share almost the same life and similar experiences, my creations touched some nerves. Some people started liking them.

Indian society, it is often alleged, refuses to grow up. There are a lot of inhibitions that constantly dog our paths. Your songs came as a rude jolt in the 1990s.

I have been a slave to music, I have served music. If an epitaph had to be written after my death, it should be: Here lies a man who tried to look for his language in music. Sadly, right now, I have not been able to serve music as much as I would love to because of my involvement in politics.

India is a land of beautiful melodies and songs. But as I started writing my own songs, I felt it was high time the lyrics came of age and thoughts. Any song, I feel, should be like a snapshot, a haiku. It can be temporal in nature; it may change the very next moment. But it should be well crafted, structured and meaningful, it should effectively capture a particular moment.

'My music challenged petty bourgeoisie Bengali music'

The love songs's lyrics still consist of sajan or sainya in Hindi and ogo, haango in Bengali. I find them puerile.

There was a time when India heard memorable yet distinctly different voices. I am citing instances from Mumbai and also from Bengal. I apologise for my ignorance of South Indian music, though I think K J Yesudas is an enviable artiste and Ilaiyaraaja a brilliant musician -- Talat Mahmood, C H Atma, Pankaj Kumar Mullick and his sonorous baritone, Mohammad Rafi, Hemant Kumar aka Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, Sachin Dev Burman, Kishore Kumar. Each of these voices had a character of its own.

But now, the voices that we hear on FM or in films are so juvenile, especially the female voices. When I was in Europe and the US, my musician friends often asked me 'Is it a ritual in India that you record all female artistes before puberty? Why are all the female voices so thin? Why is there no dimension to it?'

Now, all the female voices are so Lata Mangeshkar-ish. In the British Raj and post-British Raj days, we had great voices like Shamshad Begum or Noor Jehan. But in the days that followed, in came Lata Mangeshkar and Lata Mangeshkar and Lata Mangeshkar and Lata Mangeshkar. All the female voices then started representing a helpless woman, no matter what.

Even if the male voices sang a 'heroically yours' or 'romantically yours' tune, the female voices responded with an adolescent 'helplessly yours' refrain. And this trend still continues. I don't think such an infantile style of singing does justice to India or to any people.

You have always had a love-hate relationship with your audience. Either they put you on a pedestal and worship you or they hate you to the core. Why is it so?

I think it is because I brought in a new age. I have to say this. I am going on 61. And I have no qualms in admitting that Bengali music came of age with me.

My songs, therefore, came as an affront for many.

What was a welcome relief, a new horizon for some, was a threat for the others, who desperately held on to their old fortresses.

My songs questioned some people's premises. While my music addressed some people's premises positively, they challenged petty bourgeoisie Bengali music industry's existence. Therefore, most Bengalis belonging to the establishment just hated me.

Please don't misunderstand me -- I am not casting any aspersions here. I am just trying to make a sociological analysis instead.

I read a number of books by Lucien Goldmann, the great initiator of the Sociology of the Novel. He coins the term 'problematic individuals'. He says capitalist societies through their contradictions create types -- people who are neither here nor there. They are marginalised. I think I am one of those problematic individuals.

Music that I loved and still love is castrated music. It is alienated from life.

I feel like borrowing from Tchaikovsky here. Igor Stravinsky quoted Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in his autobiography. There, Tchaikovsky said just as a cobbler makes different shoes everyday for different feet, I make music.

My music, too, is at times utilitarian. My songs are topical, short-lived. Once the topic dies, so does a song. I never claim immortality for my songs.

'People are jealous of me'

I read quite a few books by Edward De Bono, inventor of lateral thinking -- it is a term coined by de Bono for the solution of problems through an indirect and creative approach.

In one of his books, de Bono says -- you may be a good scientist but what apparently matters more is how you sleep with a woman or with a dog or a snake. He says, and I am just paraphrasing, it does not happen in the US but England specialises in it. I think such comments stem from people's repressed sexuality.

It is true that I have married several times and I have had relationships but I have never tried to suppress that information.

You have always been pretty unabashed about your marriages or relationships. Does this brazenness bother people?

Maybe. If you ask me 'Kabir, are you in love' and expect me to turn crimson and say, 'Oh no, what do you mean?' or 'Have you made love to any other woman other than your wife?' and want me to shudder and state, 'No no, please, how can you say that? chastity for God's sake', you are sure to be disappointed. For, this kind of behaviour is alien to me.

But I do respect other people's chaste opinion of God's scheme of things in matters related to sexuality, lovemaking and relationships. All I can say is that I have never harmed any woman or I have never raped any woman, you know.

Not a single woman has ever said that I have forced her to sleep with me or kiss me.

To be honest, I think people are simply jealous of me. They see in me a man who makes good music, performs well, performs alone and draws some kind of attention.

They are pretty sure that some men as also some women are bound to like me. A handful of people, therefore, just can't take it and think something must be done about it.