| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Our policy seems to be to give away part of J&K, even though we are entitled to the entire state.'

'The Congress has done so, and the BJP is following the same policy.'

'No one is applying their mind to the legal position.'

'Kashmir is not a part of Pakistan under its own constitution.'

Aman M Hingorani, a Supreme Court lawyer, has come up with an extremely well-researched and compelling book on the Kashmir dispute, Unravelling the Kashmir Knot (Sage).

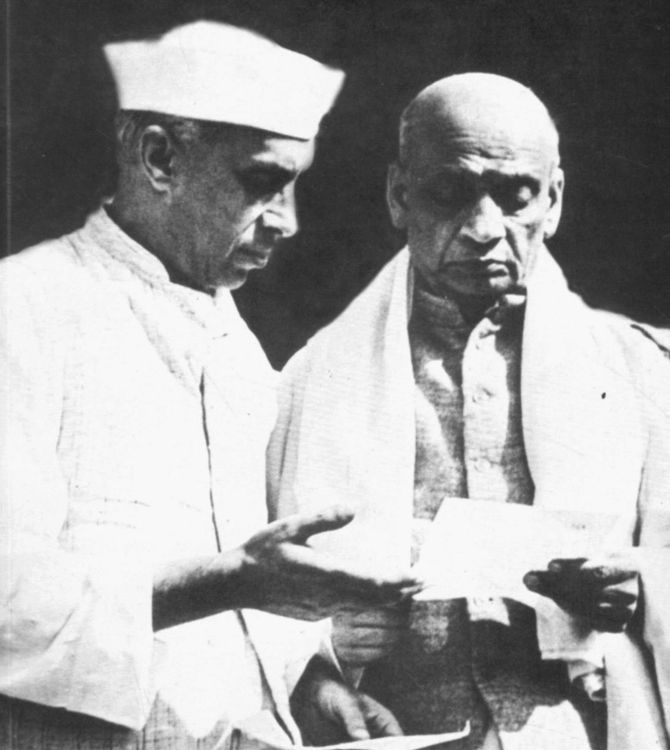

Dr Hingorani, left, below, believes it is imperative both to depoliticise the issue and then take recourse to resolving the dispute by following the legal route as a key way to achieve enduring peace.

He spoke to Rediff.com contributor Rashme Sehgal.

What made you want to do a book on Kashmir?

What made you want to do a book on Kashmir?

I, as such, have no connection with Kashmir. I had completed my LLM from the UK and was searching for a topic for my doctoral thesis. My father, who was a pre-Partition lawyer, suggested that I look at the Kashmir issue as every conceivable principle of law had been turned on its head in creating and sustaining this issue.

I felt that no comprehensive legal analysis on India's stand on J&K had been undertaken and I believed this would be an interesting area to look at academically.

The Partition of India took place because the British wanted to create a sphere of influence in the sub-continent.

Since the British had poor relations with the Congress, they felt the Congress would deny Britain military cooperation so they settled for the Muslim League and Mohammed Ali Jinnah to help them establish a separate State, namely Pakistan.

The Great Game was being played out between Britain and Russia. The British wanted to stop Russian influence southwards, where the oil wells were located. The British knew they would have to transfer power to Indian hands, but they did not want to let go of the entire subcontinent.

Jawaharlal Nehru had already stated that he did not want an independent India to be part of the Commonwealth.

Declassified British archives disclose that since the British wanted to retain a slice of India, they felt that the north-western part of India (particularly, the North West Frontier Province) could become a friendly State for their strategic, political and defence interests.

The Muslim League had been created by the British initially to communalise the Indian polity with a view to offset the freedom struggle spearheaded by the Congress.

Since the north-western region of the sub-continent was predominantly Muslim, the British handpicked Jinnah to mouth the two nation theory in order to create Islamic Pakistan.

For them, Pakistan was a means of continuing to wield power in this region.

The British outwitted the Indian leadership into letting the Congress-ruled NWFP go to Pakistan, was complicit in Jinnah's 'Direct Action.' leading to a bloodbath in Bengal, Punjab and other parts of the country, and even effected the coup in the strategically located Gilgit to hand over such territory of J&K to Pakistan after J&K had acceded to India.

The British were playing a dangerous game by stoking this religious frenzy between the Hindu and Muslim communities. They knew we would head for a bloodbath?

They were ruthless, viewing the dead and dispossessed Indians as incidental damage. Lord Mountbatten is on record as having said 'What is 200,000 (dead Indians) out of 400 million? That is one person in 2,000, isn't it. It is a fractional percentage.'

The whole world was looking with amazement at how we gave the British, who divided the country, a festive farewell.

It seems shocking that the British were working according to a blueprint to divide the country about which the Congress did not have a clue. You write about the seeming innocence of Indian politicians.

It was only a handful of Indian leaders in undivided India who were hobnobbing with Mountbatten. Following Partition, the British were heading both the Indian and Pakistani armies. We remained a British dominion till 1950.

Right up to 1948, our entire Kashmir policy was being formulated by Mountbatten heading the Emergency Committee and the Defence Committee of the Indian Cabinet.

How could we have been so naive?

We were politically naive. My sense is that very effective smokescreens had been created by the British. They cultivated Jinnah.

In the Simla Conference of 1945, they made Jinnah the sole representatives of all Indian Muslims even though he had little or no support of Indian Muslims. They identified influential Muslims to counter the Hindus and other Muslims.

They set people against each another, like they did to disintegrate the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East.

They encouraged traditional Hindu-Muslim differences to deteriorate into a killing frenzy.

Congress President Acharya (J B) Kripalani had said that if we go on like this, retaliating and heaping indignities upon each other, we shall progressively reduce ourselves to a stage of cannibalism and worse, and in every fresh communal fight the most brutal and degraded acts of the previous fight became the norm.

The entire political leadership of undivided India was naive. The Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalan has written that people who we thought had statesmanship, acumen and far-sightedness were left blinking their eyes while the British divided the country with stern calmness.

Nehru promised a plebiscite in J&K to determine the wishes of the people to accede to India or Pakistan.

Both modern day India and Pakistan are creations of British statutes enacted to give effect to the political agreement driven by the British and the Muslim League, and eventually accepted by the Congress, to partition the sub-continent.

According to this agreement, the British provinces were to be partitioned according to the two nation theory, which I have explained was conceived by the British to create Pakistan.

However, all the princely states were to regain full sovereignty and that sovereignty vested in the ruler, regardless of the religious complexion of the people of that state.

It was the ruler alone who could offer accession. These British statutes were accepted by India and Pakistan. Pakistan had taken the correct legal position that princely states were sovereign in the full sense of the term as of August 15, 1947.

J&K was a sovereign state on August 15, 1947, which is why it could accede to sovereign India in October that year. Pakistan had no say in the matter. But because of the controversial accession of the princely states of Junagadh and Hyderabad, the Congress formulated a policy making the wishes of the people relevant to the accession of a princely state.

Nehru then agreed that this would apply to J&K.

But the question to be asked was whether Nehru could make a promise that was contrary to the constitutional law then in force and which was accepted by both India and Pakistan -- namely, the British statutes.

These statutes -- the Indian Independence Act, 1947 and the modified Government of India Act, 1935 -- clearly stipulated that it was only the ruler who was competent to decide the future of his princely state.

The Instrument of Accession by the princely states was unconditional and not subject to the wishes of the people.

Yet Nehru sent cables to Liaquat Ali Khan and to world leaders that the accession of J&K to India was subject to the reference of the people of that state.

New Delhi kept reiterating this stand even in its White Paper on J&K thereby creating a feeling of injustice amongst the Kashmiri people when no reference was held.

It was overlooked by Nehru that once a political decision has been crystallised into law, the executive has to accept this for it cannot act beyond its power.

New Delhi has acted beyond the scope of its power by promising self-determination and plebiscite in J&K.

We are seeing terrorist movements in the guise of a freedom struggle because Nehru said the Kashmiris had the right to self-determination.

We created the problem in the first place.

Did Mountbatten play a devious role and outwit the Indian leadership to take the Kashmir problem to the United Nations?

The British did not need the whole of Kashmir. They just needed the northern areas of J&K for the Great Game with the Russians, and the slice of land known as 'Azad Kashmir' to protect Pakistan from liquidation should India try to vacate the aggression.

At the time of accession of J&K, Mountbatten said he would sign the Instrument of Accession (as the governor general of the Dominion of India) only if Nehru agreed to hold a plebiscite in J&K to determine the wishes of the people.

He then persuaded Nehru to commit to plebiscite before the UN Security Council.

The Security Council called for a cease-fire, without requiring Pakistan to first vacate the areas that it had occupied through aggression.

Thus, in the guise of a cease-fire, the Security Council allowed Pakistan (and through Pakistan, the British) to retain precisely those areas of Kashmir which the British needed for the Great Game. It was a trap laid at the Security Council, which is a political entity.

Interestingly, under the British statutes, the accession of J&K to India was unconditional, final and complete. But the British representatives argued to the contrary before the Security Council.

The Security Council overlooked that when the UN accepted India as a member State, it accepted its territorial integrity, which includes the entire territory of J&K.

Furthermore, Kashmir is not a part of Pakistan under its own constitution.

What was the Indian stand after the Security Council debacle?

Since then, the Indian policy seems to be of territorial status quo and of converting the LoC into the international border.

That is, India would give up the territory of J&K occupied by Pakistan and China. At one time, the Supreme Court had held that Parliament can cede Indian territory.

But after the formulation of the basic structure doctrine by the Supreme Court in 1973, even Parliament has no power to tinker with the basic structure of the Constitution.

This, according to the Supreme Court, includes unity of the country. As a result, Parliament today cannot give away Indian territory.

Unfortunately, our policy seems to be to give away part of the state, even though we are entitled to the entire state of J&K and we cannot legally give away any part of Indian territory.

Following the policy of status quo, we handed over our own territory to Pakistan -- we gave away Haji Pir we won in the 1965 War, we gave away territory we had won in Kargil.

Under what provisions of law are we handing over our territory to Pakistan?

The Congress has done so, and the Bharatiya Janata Party is following the same policy. No one is applying their mind to the legal position.

In fact, China is asking Pakistan (who has no right to any part of J&K) for legal documents for the Northern Areas in order that they can safeguard their economic investments in those areas.

Your book talks of two steps to resolve the Kashmir issue.

Your book talks of two steps to resolve the Kashmir issue.

Since we created doubts about the unconditional nature of the accession of J&K to India, internationalised the Kashmir issue and conferred a disputed territory status on J&K, we need to, as a first step, confirm, as it were, our title deeds to J&K, which would clearly show that the whole of J&K belongs to us.

The only body that can look into this issue is the International Court of Justice. We need a finding from this body because it will be binding on both India and Pakistan and all other members of the UN. Otherwise, no one is going to listen to us.

If the International Court of Justice gives a verdict in our favour, then other nations will no longer be in a position to say that what is going on in J&K is a freedom struggle and will have to ask Pakistan (and China) to vacate the territory of J&K under their occupation.

If we fail to convince the International Court of Justice, we fall back on our existing stand and so we lose nothing.

Having the correct legal position will help alter the current political discourse and swing political opinion in our favour to create a momentum for winning the confidence of the people. But law alone will not resolve the Kashmir issue.

The second step would be to regain the moral authority to be in J&K and to undo past mistakes.

Once we make the international community accept that J&K is part of India, we must restore the sanctity of Article 370 of the Constitution, roll back the Armed Forces Special Powers Acts and try new methods of conflict resolution, and address the adverse ground realities.

The chief justice of India has rightly said that we need to win over the hearts of the people in J&K.

Are you optimistic?

The Kashmiris generally feel that they have been backstabbed. Pakistan believes that Kashmir belongs to them. Debates in Indian universities are about whether we are an occupying army.

The misconceived policy of territorial status quo is implicit in the Simla Agreement and the Lahore Declaration.

We need to depoliticise the Kashmir issue by subjecting it to a legal analysis and then take steps to change the current political discourse, both nationally and internationally.

We need to reclaim moral authority in J&K.

The way forward suggested in the book is not an easy fix, but is the only viable option we have.

Whether we will be able to win over the confidence of the people of J&K depends, in the ultimate analysis, on the character of the Indian State and of the men and women who run it.