| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Until we have these (kinds of) patients come down in numbers, the fear, the mortality is always going to be there.'

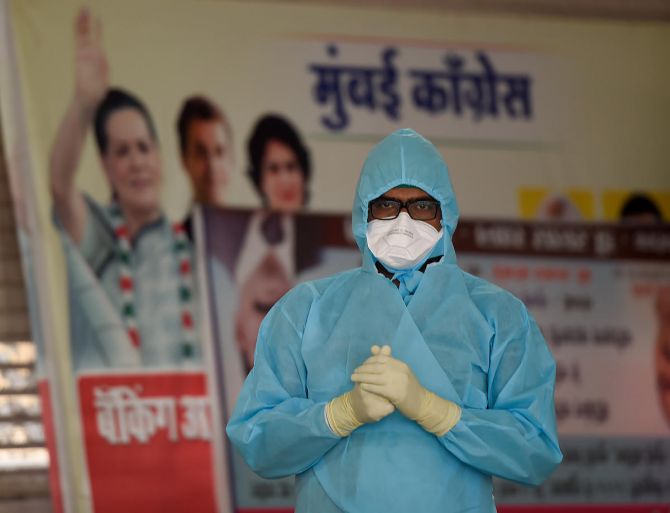

This Mumbai emergency care doctor has had two ways of seeing COVID-19 over nearly the last six months.

He has been the man in front of the mask, administering the crucial oxygen that has often saved many patients' lives.

He has been the man behind the mask, receiving oxygen that helped him finally recover from a moderately-serious case of COVID-19.

Dr Rahul Pandit, head of intensive and critical care at the Fortis Hospital, Mulund, north east Mumbai, therefore has an extensive understanding of how COVID-19 sweeps in and the deadly havoc it can wreak and how to face it strongly, resolutely and safely.

The critical care specialist, who qualified at the Grant Medical College, Mumbai, and in Australia and is also a visiting consultant on the faculty of a hospital in New South Wales, Australia, serves on the Maharashtra state task force for COVID-19. He has over 20 years of experience.

Dr Pandit sorts through some of the facts and realities of the viral illness, even as India tops world records, recording the highest COVID-19 new cases daily for nearly three weeks.

The former COVID-19 patient and physician warns about the importance of India doubling precautions, as numbers come down in some areas and shoot up, staggeringly, in other regions.

Indeed, between the day the first case was recorded, in late January 2020, and end July, India reported 1.6 million cases.

And now post lockdown and smart re-opening, that number nearly doubled with 1.5 million cases being reported in August alone!

In Part 1 of this interview to Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com, Dr Rahul Pandit talks about his experience and findings.

Personally, what was it like to go through COVID-19.

How bad a case did you have?

I did need oxygen.

But it was limited to that.

For a couple of days, I was on oxygen.

Then I gradually improved.

It is a terrible disease, isn't it?

By god's grace it wasn't that bad.

I just needed a couple of litres of oxygen for a couple of days.

I had probably 10 to 20 per cent of my lungs involved, which improved over a period of time and that was during the worst period.

Yes, when hospitals didn't know that much about taking care of the COVID-19 ill in April?

Yes.

What is the situation looking like now?

We are constantly being hit with statistics about the biggest rise in cases in India since the epidemic began and other figures.

What's happening in Mumbai, at least, is that we've plateaued and we've been plateaued for last five weeks or so, approximately.

We are between 1,100 and 1,200 new cases daily.

Some days we have below a thousand.

But most days, we have somewhere between 1,100 and 1,200 cases.

Plateauing usually means that it should hopefully go down, if we don't do anything silly.

And we have been holding our nerves, right now -- by not opening up schools and local trains and everything.

We seem to be moving in the right direction is what I will say as a healthcare professional.

Of course, economists may have a completely different view.

And I feel for the economist, as well.

Both are wheels of the same wagon and we need to balance both of them together.

Otherwise, there's going to be a problem.

So gradual, smart unlocking is what is being done right now and that's what we need to continue to do.

If we get it right, this kind of plateauing should start going down.

And we should be able to flatten the curve further.

We have flattened the curve to a plateau, but we haven't really brought it down yet.

What is actually the scene on the front lines, since you are right there?

How bad is it on the front lines right now in hospitals and ICUs?

ICU bed demand is still there -- very, very high.

And there are people there who are very critical still.

However, what I'm hearing - and this is just the last few weeks -- that that some of the hospitals are now having beds available, even ICU beds, which was not the case three, four weeks ago.

Three or four weeks ago, by 11 o'clock in the morning all ICU beds would be full, literally (in the city).

I would do a round in the morning and clear up patients to go out from the ICU to the ward and we would have new patients waiting to come in.

Our ICU has not yet gone to that phase.

We are still inundated with cases and we still have a lot of patients waiting to come in.

I feel we should be able to cater to everybody, but there is only so much we can do.

We still have a fair number of patients who are intensive care.

The critical patient numbers have not come down.

Overall, numbers might have come down, but we still have a fair share of critically ill patients.

That's what bothers me.

Until we have these (kinds of) patients come down in numbers, the fear, the mortality is always going to be there.

We need to send out a message to seek treatment early especially for those who are above 60 years of age and have comorbidities.

There must be a lot of pressure on you in terms of time and the number of patients you have to see and it would be very stressful.

Yes.

I would not say it is stressful, that's what we are there for and the major part of the stress is taken over (distributed) if you have a good team and a big team.

That's where we are probably a little ahead of other places because we have a very, very efficient and big team to look after things.

What are the chances of getting COVID-19 again?

Like say for somebody like yourself?

Oh, I think it is very real. It is very real.

This immunity passport is questionable.

It probably offers some amount of immunity in the initial few months.

How long does it stay? We don't know.

Because the strain of COVID-19 might mutate?

Not only mutate, but you may lose your antibodies and they may go down to a level where they may be ineffective.

Even if it doesn't mutate, you could still have the same virus infect you.

Same species infect you.

Since you are a doctor and specialist working on the frontlines, who has also suffered COVID-19 too, what do you feel is the ideal regimen of treatment required for this illness?

In the current scenario there are a few things that work the best:

If you are within your first few days of illness, or very specifically within the first three days of illness, then an oral antiviral like favipiravir (an antiviral that was first used to treat flu in Japan) probably should be taken.

If you are between your fifth and 10th day of illness and you start becoming hypoxic (less oxygen in the blood), then these things definitely -- oxygen, oxygen, oxygen, remdesivir (antiviral), low-dose steroids and good supportive ICU care.

Good supportive ICU care and ward care is the backbone of the treatment.

If you are not going to get good supportive care -- and when I say good, supportive care, I mean prone position, ventilation, oxygenation, high-flow nasal cannula* - then none of these drugs are going to work.

You need to sleep face down as much as you can.

You need to basically keep on doing oxygen saturation monitoring, to make sure that your oxygen saturation is above 94 per cent all the time and see if oxygen supplementation is required.

If that is not enough, the patient has to be moved up to the next level of therapy like high-flow nasal cannula or a ventilator.

But don't delay.

Most city hospitals all over the country have been overburdened.

So how much good ICU care is actually available?

That's a very pertinent question.

There are a number of ICU beds available.

But whether all of those beds are actually manned by good intensivists or not is a big question.

I think, only a handful of beds in the country are actually managed by good intensivists.

And it is not the bed.

It is the person behind the machine which actually makes the difference.

You need a good infrastructure, good nurses, trained ICU nurses, trained intensive care doctors, juniors as well as seniors, trained paramedical staff, trained physiotherapists, dieticians, (all of whom) know exactly what they're doing.

It's a whole machinery in itself.

If you don't have that machinery, none of the infrastructure - infrastructure building exercise of just buying ventilators, building big hospitals or putting up jumbo or temporary facilities -- are actually going to make a difference.

It's a person who is going to make a difference, not the infrastructure.

But wouldn't you say that, even if many of our ICUs are not functioning up to par, between April and August, we have taken some important steps in terms of understanding how to manage the illness?

Of course, of course.

There has been exponential rise in the understanding of the disease as the pandemic has progressed.

And we have had several people step in and do the role of an intensive care doctor or an infectious disease doctor.

Hats off to all the people who actually stepped in and took up the roles, because otherwise we would have struggled as a country.

And it's not just in India, but everywhere in the world.

There are only so many specialists in a field.

This pandemic has really burdened some of us.

ICU care has been at the forefront.

Infectious disease care has been at the forefront.

And pulmonology has been at the forefront.

These three specialties have actually taken the majority burden of the pandemic -- ICUs being the topmost.

When you say exponential, could you provide some sort of indication?

Let's say, by example for Mumbai, what do you mean by an exponential rise in understanding?

We have now written protocols.

It is a live document, gets updated every now and then, as a new data comes in.

We have everything written up on how to do it.

We have gotten anesthetists and physicians to take up the role of temporary pulmonologists.

We've got, now, good training and short seminars, which we have had for the last four or five months, where we have updated the skills of the people who are not used to the intensive care environment.

And a lot of them have actually voluntarily come and helped us out, which has helped us to build up the manpower to the optimum level.

I would probably say now we have an optimum level of manpower.

A lot of people are there to make sure things are done in a safe manner, which, obviously, when we started off, we were caught off guard, and we were really struggling to have enough people on hand.

But that's not the case now. We have enough people who know what they are doing, who understand what is expected of them and they perform to the best of their ability

*a kind of non-invasive ventilation whereby heated, humidified, high-flow nasal cannula (via a tube) oxygen is administered.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/ Rediff.com