| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Non-separation of religion from politics is India's most daunting challenge'

Dr Madhav Godbole is one of India's most distinguished civil servants. Union home secretary in Narasimha Rao's government, he resigned from the Indian Administrative Service in March 1993, a couple of months after the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

He has written 26 books on Indian policy issues. The latest being India - A Federal Union of States - Fault Lines, Challenges and Opportunities (Konark Publishers). An extremely important book for our times, it analyses complex and sensitive issues and most importantly, provides solutions for the future of federalism under which Centre and states function in India.

In a detailed interview with Rediff.com's Archana Masih, Dr Godbole discussed the critical issues confronting India and provided some fresh ideas for crafting a better Republic.

India has changed since the Constitution was framed 70 years ago. In what ways has the country changed and what revisions are required for the India of today?

We seem to be oblivious of the major challenges facing this country.

The first one, of course, is secularism in a multi-religious, multi-ethnic, multi-racial country like India.

The Constitution has provided provisions for the right to freedom of religion, culture and educational rights of minorities.

The Supreme Court has ruled that secularism is a part of the basic structure of the Constitution. Minorities constitute twenty per cent of the population and disregarding secularism is not in the long-term interest of the country.

The BJP's propagation of a Hindu Rashtra poses a serious threat to secularism. Hindu Rashtra is not going to keep India together.

The first major fault line is the non-separation of religion from politics which poses a serious danger in the future. Separating religion from politics is a matter of great urgency. Unfortunately, there is no indication that this issue will be taken up in the near future.

It could have been done in the early years of Independence, in fact, even up to when Rajiv Gandhi was in power with a massive majority.

Indira Gandhi had a large majority and, of course, Jawaharlal Nehru who was prime minister for 17 years, but none of them took it up.

In the last twenty years, the ideology of the party in power has completely changed that we are now on a different path altogether.

This is our first and most daunting challenge which has been neglected.

Your book examines the nature of Indian federalism, what changes are required in regard to Centre-state relations? How is Indian federalism different from other countries?

The concept of Indian federalism is different from the conventional understanding of the term 'federalism'.

Indian federalism is not the coming together of sovereign states that acceded some powers to the Centre to form a federation.

The Indian states are a creation of the Constitution.

When India got freedom there was British India and 544 princely states. The integration of the states was a major problem which was dealt very efficiently by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

Only after that did India emerge as one country.

Centre-State relations are defined in the Constitution in the background of Partition. Naturally at that time a strong Centre was needed to hold the country together.

I feel that over a period of time while it is important to have a strong Centre, there are many other important issues which need to be attended as well.

What are some of those important issues?

For example, linguistic states. When the states were created it was not known that this issue could lead to sub-nationalism which digresses from the national objective.

There was a major demand for linguistic states and the Congress itself supported the demand. Nehru and Patel had serious reservations about the dangers of linguistic sub-nationalism, but they had to concede to the demand.

Seven decades later, we are now at the next stage where we are talking about splitting linguistic states into two or three.

The ideology during Nehru's time was that there should be larger states. Nehru wanted Bihar and Bengal as one state. He certainly made an effort to have a bilingual state for Gujarat and Maharashtra which ultimately could not happen because of internal tensions.

But now we have gone to the other extreme where the BJP's ideology propagates smaller states.

How will smaller states be reconciled with the idea of a federal arrangement needs to be given serious thought.

What challenges will the delimitation of Lok Sabha constituencies pose to Indian federalism?

The delimitation of Lok Sabha constituencies is to be done after 2026 and will pose major challenges.

In keeping the present formula of representation, you will find the representation of southern states will reduce and representation of northern states will increase substantially.

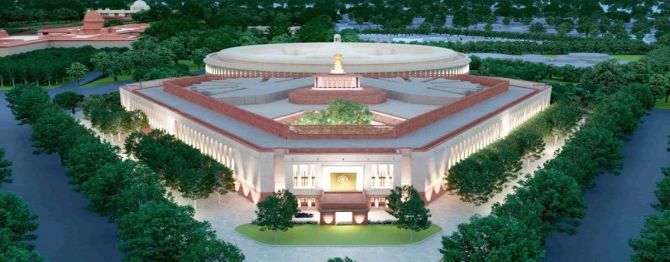

When the central government is building a new Parliament House, it needs to be seen whether a Lok Sabha of 1,200 or Rajya Sabha of 700-800 is something they should aim for.

The important question is how to give representation to various parts of the country.

These are sensitive issues which can't be left till the last minute.

Another point you raise is whether there should be only one national domicile or state domiciles should continue to be recognised as it is at present.

It is a worrisome trend in the last two, three years that states are trying to reserve employment opportunities for people domiciled in that state.

Should there be a state domicile at all in India is a question I have raised in the book.

The Supreme Court at one time had taken the view that there is one national domicile in India under the Constitution, but a later ruling by a full bench of the Supreme Court took the view that there is a provision for providing state domicile.

I can understand that that is relevant for purposes of laws which are to be applied only to the given state, but it also leads to a contradiction.

On the one hand is the concept of state domicile and on the other are the fundamental rights of citizens to move freely/reside in any part and seek employment opportunities all over the country.

Each one of these fundamental rights are being compromised by the state domicile laws where states are competing with each other in trying to reserve not only 50%-60% but up to 90% vacancies in employment opportunities to those residing in their state. This is not just confined to government jobs, but also in the private sector.

This is the negation of India.

India cannot continue like this. We have to address this problem, but since it is a politically sensitive issue no political party is willing to address it.

This is a major fault line that is staring at India and we need to take notice of it.

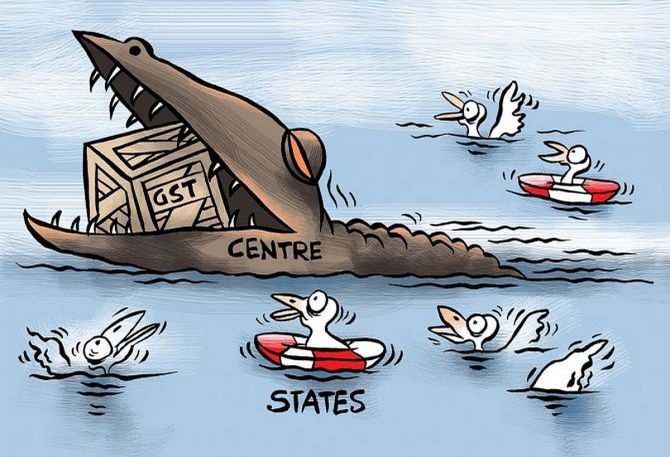

You also argue that a common market is what will keep India together and GST with all its shortcomings is a giant step towards cooperative federalism. What are some other measures that need to be undertaken towards achieving this?

A strong Centre is not enough to hold India together. We need something more and that is economic integration.

One market will keep India together -- a natural intercourse in terms of finance, economics and commerce.

There is a provision in the Constitution that India will have one market, but it was compromised and watered down by a number of other provisions where the states could easily put 'reasonable' restrictions.

This term 'reasonable' was interpreted in various ways, over a period of time.

In many states there was an entry tax on goods coming from outside the state and various other restrictions on so called stocking and marketing of goods.

The situation arose where restrictions were imposed, not just by certain states, but also by the Centre in the so-called larger interest of the country.

The time has come for us to take a look at the Constitution and what needs to be done to make India a unified market for purposes of all kinds of transactions.

This is what will keep India together.

There was a provision provided in the Constitution by the founders about appointing the trade and commerce authority of India. 70 years after the adoption of the Constitution, we still have not set up such a commission.

This should not be a statutory commission, but a Constitutional commission so that it is able to deal with the pressures and counter pressures from states.

Therefore, it must have the power to achieve the objective of a common market.

GST is a step in that direction. What is your assessment?

The success of the Goods and Services Tax is success of cooperative federalism.

Tamil Nadu is questioning whether there should be 'one state one vote' in the GST council. These are counterproductive moves, according to me, because due to the pandemic, the revenues from GST are not adequate. There were large losses which had to be recouped to the states.

The central government has adopted an unacceptable position that borrowing should be done with the Centre's permission by the states individually.

Naturally, there was a clamour about this. The Centre took a totally clinical view of the matter. A change of the mindset is required by both Centre and the states to make this a grand success.

There is a long way to go in terms of covering a number of areas under the purview of the GST, but all this is stuck due to political rhetoric.

It needs a strong political direction and on that will depend whether cooperative federalism will be a success in this country or not.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com