| « Back to article | Print this article |

'What hurts people most is dynastic impulses and corruption under a family-ruled Congress party -- and Nehru has borne the brunt of it... I cannot be blinded by how the Nehru family has functioned but just as Gandhi can't be judged by his descendents, why should Nehru?' asks political scientist Ashutosh Varshney.

'What hurts people most is dynastic impulses and corruption under a family-ruled Congress party -- and Nehru has borne the brunt of it... I cannot be blinded by how the Nehru family has functioned but just as Gandhi can't be judged by his descendents, why should Nehru?' asks political scientist Ashutosh Varshney.

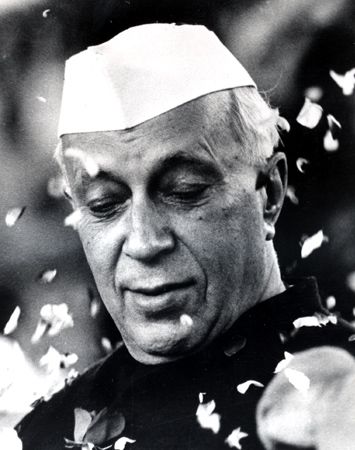

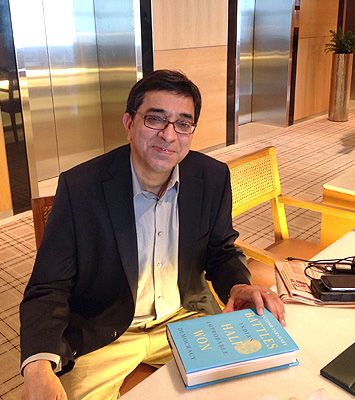

If Gandhi is the father of Indian nationhood, Nehru is the father of Indian democracy, Brown University Professor Ashutosh Varshney, below, right, writes in his latest book Battles Half Won, India’s Improbable Democracy.

The book is an engaging insight into the triumphs, failures and survival of Indian democracy which Varshney calls 'the institutionalised common sense of Indian politics.'

An alumnus of Jawaharlal Nehru University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a former professor at Harvard, the Uttar Pradesh-born Varshney is a leading scholar on India.

On a recent visit to Mumbai, he spoke to Rediff.com's Archana Masih about Jawaharlal Nehru's remarkable, if not impeccable record, the need for Narendra Modi to redefine his relations with the Muslims and how India has moved beyond the riots era.

Part I of the interview: 'AAP's beginning has been promising, but its struggle lies ahead'

Part II of the interview: 'Modi is a very exciting and polarising figure'

In Battles Half Won, India';s Improbable Democracy, you write that the only cleavage that has the potential to rip India apart is the divide between Hindus and Muslims. Has this division become deeper in today's India?

After 1947, the most anxious moment was the 1990s. Nothing promotes polarising anxieties more than rioting.

India now has a different kind of problem and that is the discrimination against Muslims. For example, Muslims can't get flats -- discrimination and everyday biases have to be fought.

That is true of Dalits as well except that they are politically more powerful. It is a suffering that Muslims share with Dalits and the lowest OBCs (Other Backward Classes).

My argument in the book is that India in all probability -- not certainly -- has gone beyond the riots era now.

Riots will not disappear, but the frequency and deadliness will certainly decline.

Instead of riots, India is likely to see hi-tech terrorism and everyday discrimination.

Many India Muslims feel that Indian society does not treat them fairly. They have some concern about riots after seeing what happened in Muzaffarnagar, but I don't think it wakes them up in the middle of the night.

The '80s and '90s were truly alarming. That was truly an anxious moment in the history of the nation. It was the worst moment for Hindu-Muslim relations after 1947-48.

Even Mr Modi's arrival in power, should it happen, will not easily reproduce the 1990s.

Only riots and mass incarceration can produce the kinds of anxieties that Indian Muslims and a lot of liberal Hindus felt in the 1980s, 1990s and in Gujarat in 2002.

It is not that Muslims of India love the prospect of Modi coming to power. What I am saying is that if he does come to power he will certainly produce greater anxieties among the Muslims than they currently have about the functioning of the polity.

But it won't match the depth of anxiety that they had felt in the '80s, '90s. Those were existential threats.

Existential threats are different from anxieties. I am making a distinction between existential threats and anxieties.

Mr Modi will also have to figure out how to redefine his relations with the Muslims. So far, his language is very coarse but he has not demonstrated anti-Muslim virulence since the kutta pilla episode of July.

That showed a certain coarseness of language, it seemed like he was equating Muslims with animals and he should be critiqued for that, but I don't think he meant to express virulence.

He has been trying to check himself since his last victory in December. He has come on the verge of saying sorry, but he pulls back. He is trying to redefine his relationship with the Muslim community, but it is not happening yet.

It can't be that the Muslim community has to redefine its relationship with him. It has to be a two way process.

A leader has to make a greater attempt and make gestures of conciliation.

If he doesn't want to say sorry, then he has to express regret, but the regret has to be primarily to the Muslim community of Gujarat.

You say in your book that as Gandhi is the father of Indian nationhood, Nehru is the father of democracy. Nehru and his policies invite most criticism, especially among the young? Why?

You say in your book that as Gandhi is the father of Indian nationhood, Nehru is the father of democracy. Nehru and his policies invite most criticism, especially among the young? Why?

The young generation of India sees Nehru through the Nehru family which has become extremely unpopular. The Nehru family has produced no one like Nehru.

Mrs Indira Gandhi developed seriously authoritarian proclivities, but I don't think one can claim that Mrs Gandhi was corrupt. Maybe she was, maybe she wasn't, we don't know.

The biggest critique that political science has made of her is her authoritarianism. The Emergency colours her forever.

Rajiv had a very short stint, we don't know what he was capable of. He did generate a lot of energy, but it quickly dissipated and by the time Bofors happened, he lost his base so rapidly that someone like V P Singh could throw him out.

The Congress' seats were halved from 1984 to 1989. Since then we have his widow who at least has two victories to her credit, but the idea that the Government of India has been run primarily according to the wishes of 10 Janpath offends people.

Rahul generated a lot of enthusiasm in 2009, but he hasn't had a single major victory since 2009. That he has not been able to reform the Congress party is an indictment.

But what hurts people most is dynastic impulses and corruption under a family-ruled Congress party -- and Nehru has borne the brunt of it.

Secondly, Nehru's economic policy was flawed. Whether post 1991 models were available in the 1950s is a different question.

In my book I make the case that these models were not available and Nehru was not the only one practising central planning, almost every political leader was doing the same and had distrust of market forces.

The world had just come out of the Great Depression and the Soviet Union in a matter of 30 years of planning had become a superpower.

So the space for market-based models wasn't there and you can't blame it entirely on Nehru, but it is true that India only saw a 3.5% growth rate during the Planning era -- and the father of planning was also Nehru.

Nehru was the father of Indian democracy, a great patriot and someone who contributed massively to the building of the nation after Gandhi's death. All these go in his favour.

As a political scientist I cannot be blinded by how the Nehru family has functioned, but just as Gandhi can't be judged by his descendents, why should Nehru?

The judgement of the young generation should be different. It is wrong to judge Nehru through the dynasty. Also, Mrs Gandhi was not Nehru's successor. Lal Bahadur Shastri was.

She was Shastri's successor, she ran for office and defeated Morarji Desai. She also ran for the Congress presidency during Nehru's time and was president for a year.

It is unfair to judge Nehru from the prism of his descendents.

Do you believe the India that goes to the polls in April is a different India which went to the polls five years ago? What has changed? What has not changed? Is this an election that has never been before?

Of the 760 to 800 million voters, roughly 150 million will vote for the first time. That itself is very distinctive.

Secondly, if the urban middle class returns to voting, that will be another electoral novelty.

The middle classes voted vigorously in the 1950s, '60s, '70s and they propelled India's freedom movement. But their disenchantment began with the rise of the OBCs in Indian politics.

I am not suggesting in any way that OBCs don't have a middle class, but India's middle is predominantly if not wholly upper caste; predominantly if not wholly Hindu; predominantly if not wholly urban.

The return of middle classes to electoral politics will not be a historic novelty, but a novelty for the last 20 odd years.

So 150 million new voters, the likely return of the middle class to electoral politics and a party which is going beyond the three-and-a-half master narratives of Indian politics: First, secularism which has been abused so much that that narrative has lost its appeal. Secondly, Hindu nationalism; Thirdly, justice for lower castes; regionalism as a semi fourth.

The AAP (Aam Aadmi Party) is breaking free of all these. It is obviously causing a great deal of excitement.

You can't say that this is an election you haven't seen ever, but this is a kind of election we have not seen in a long time.

What were the other elections that can be seen as a turning point?

India's first election in 1952 is described as a 'leap in the dark' because no poor country of this size had ever practiced democracy.

Ballots went on camel backs to the farthest hamlets of Rajasthan and on boats to some of India's islands.

The 1967 polls after Nehru were a new kind of election. 1977 was a turning point, so was 1998-99.

We shouldn't say 2014 election will constitute a historic novelty, we should say it will constitute a novelty of recent times.

We shouldn't say 2014 election will constitute a historic novelty, we should say it will constitute a novelty of recent times.

Images: Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first and longest serving prime minister, was the father of Indian democracy who contributed massively to Indian democracy, says Professor Ashutosh Varshney. Photograph: India Abroad Archives. Bottom: Professor Ashutosh Varshney. Photograph: Archana Masih/Rediff.com

Buy Battles Half Won, India's Improbable Democracy at the Rediff Bookstore!