| « Back to article | Print this article |

In an era when the misguided youth of today are trying to build political careers by subscribing to divisive ideologies, they need to look to independent thinking icons such as Acharya Kripalani, says Mohammad Sajjad.

The current generation of India's students and youth are perhaps not as fortunate as their counterparts in the decades of the not so distant past. During the 1920s they had Bhagat Singh; during the 1930-1940s they had Nehru and Bose; and after Independence, during the 1960s and 1970s, they had Ram Manohar Lohia (1910-1967) and Jayaprakash Narayan (1902-1979).

JP and Jiwantram Bhagwandas Kripalani fought against Indira Gandhi's dictatorial behaviour, and against her infamous Emergency which she imposed on June 26, 1975. Many tend to look at the current dispensation as worse than that because sections of the media now are seen to be hand-in-glove with the anti-poor and anti-minority regime today.

This muzzling of dissent assumes alarming proportions with a spurt in fake news, spread not only through social media but even some television channels are indulging in spreading hate and prejudice.

Faced with huge unemployment, growing economic recession, and deepening social inequalities, sections of the youth are resorting to lynch gangs and subscribing to muscular exclusionary nationalism.

The latest instance of such lynching and majoritarian violence came from the town of Sitamarhi in north Bihar where an old, poor, Muslim, Zainul Haq Ansari, was lynched and burnt to death by a mob going to immerse the Durga idol on October 20, 2018. This happened in the police presence.

Some writings about Kripalani on some news portals, in recent years, have not subjected Kripalani to a holistic evaluation. And hence this column.

It may seem ironical that Sitamarhi, having become infamous as one of the most riot-prone regions of Bihar, was one of the first Lok Sabha seats to elect a non-Congress member.

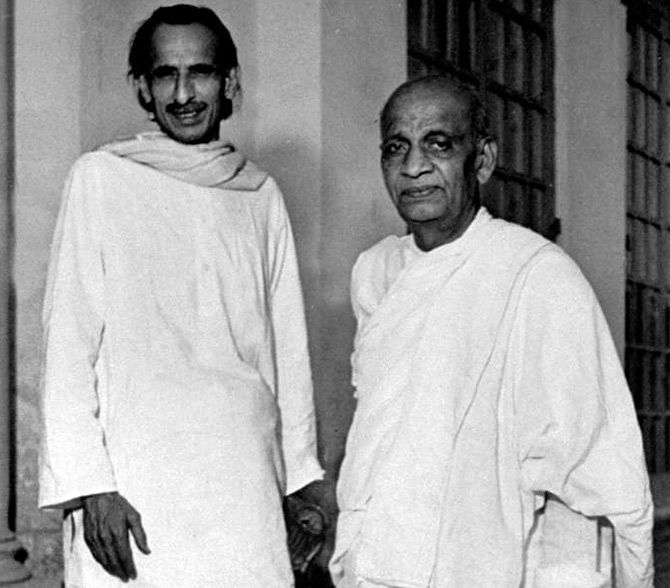

It was none other than the grand Gandhian-Socialist, J B Kripalani. He was elected in 1957 as a nominee of the Praja Socialist Party. Nehru, in order to ensure his victory, did not field a Congress nominee against him.

In 1962, he contested against the then defence minister, V K Krishna Menon, from North Bombay and lost. In 1963, Acharya Kripalani won against Hafiz Ibrahim of the Congress from Sambhal in a bye-election which came about after the death of Hifzur Rahman Seohaarwi (1901-1962), who had subjected the Muslim League's communal separatism to the severest criticism in his Urdu columns and which were later compiled as Tehreek-e-Pakistan Par Ek Nazar.

Sitamarhi was also one of the first seats to have elected an OBC candidate, Nagendra Yadav, in 1962 (who was re-elected in 1967 and 1971). Notwithstanding its educational backwardness, Sitamarhi thrice elected academic parliamentarians -- in 1957, 1977 and 1984 -- namely, Professor Kripalani, Professor Mahanth Shyam Sundar Das (son-in-law of the famous Hindi writer and Socialist, Rambriksha Benipuri), and Professor Ramshreshtha Khirhar, respectively.

The life of Kripalani, a Congressman, Gandhian, Socialist, parliamentarian, and writer, spanned almost a century. As a young man he saw the rise of Mahatma Gandhi to centrestage in Indian politics; and in old age, the fall of the Janata Party government from power.

A social and political activist for some 70 years, at no point did he ever compromise his views or principles to suit those who were in power, or to curry favour with them, recalls T N Chaturvedi in his foreword to Kripalani's thick autobiography, My Times: An Autobiography, published posthumously in 2004.

From 1912 to 1917 he served as a professor of English and history at the college in Muzaffarpur, later named after Langat Singh (1850-1912). It was there that Kripalani played host to Mahatma Gandhi in 1917 when the latter was en route to Champaran for the famous satyagraha against European planters. Because of this association, Kripalani was jailed.

Subsequently, he taught at BHU (1919-1920), and was principal, Gujarat Vidyapeeth between 1920 and 1927. During 1934 and 1945 he was general secretary of the Congress, and in 1946, he became president of the Congress.

In 1950, despite Nehru's support, he was defeated by Patel's candidate Purushottam Das Tandon for the post of Congress president. After this, he left the Congress and was among the founders of the Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party. It eventually merged with the Socialist Party and became the Praja Socialist Party.

He left the Congress on a principled position. Nehru maintained that the president of the party (Congress) should not interfere in the everyday affairs of the government.

His wife Sucheta (1908-1974), however continued with the Congress, served as Union minister in various portfolios, and became the first lady chief minister of Uttar Pradesh (1963-1967).

JB's 1,000 page memoir testifies his critical engagement and encounters with Gandhi. His engagement with Nehru too was critical. Kripalani's memoir also scrutinises Maulana Azad's account about Partition in his India Wins Freedom (pages 183-184), where Azad sort of blamed Nehru, Patel and even Gandhi.

Kripalani has devoted a whole chapter, Setting the Record Straight wherein he asks (page 691), 'why Maulana himself was silent about it in the Working Committee. Why did he not raise his voice of protest there as Ghaffar Khan did? If he had, and the two had been joined by Dr Syed Mahmud and Asaf Ali, in opposing Partition, they would have been four and they would have had the powerful backing of Gandhiji'.

From 1967 to 1977, he kept working for an anti-Congress united coalition. During Emergency he openly criticised Indira, led public demonstrations, and in 1977 wrote that ousting a dictatorial regime indicated growing political consciousness, and that 'those who said that freedom is required only by intellectuals and the cultured few have been proved wrong. It was required by the many, the poor, and the despised in India'.

In 1950, Kripalani also launched a weekly, Vigil. Its main objectives were to 'educate the people to insist that the authorities should adhere to the broad policies and programmes of Gandhiji and to raise their voice against corruption in the administration and the rampant black-marketing and tax-evasion in commerce', which was disliked by Sardar Patel, who tried to prevent its reproduction by other newspapers (pages 735-737). It ran for a decade.

Kripalani was the first ever member of independent India's Parliament to move a no-confidence motion in the Lok Sabha, in August 1963, immediately after the war with China.

With the above quick and synoptic recounting of Kripalani's engagement with almost every social, economic, and political issues, one is surprised that his memoir is almost completely silent about communal violence.

His silence is even more surprising because, one of the most heinous incidents of communal violence took place in Sitamarhi in 1959, when he was representing this seat in the Lok Sabha.

Of all the north Bihar districts, Sitamarhi-Sheohar, part of the then Muzaffarpur district, has historically been most prone to communal violence.

On April 17, 1959, a riot broke out in Sitamarhi town, killing as many as 50 people, mostly Muslims. A false rumour had spread in a cattle fair that a cow had been slaughtered, whereas the cow was subsequently recovered from Janki Asthan.

Nehru, having visited Bihar and having addressed several meetings, wrote, 'The rumour (of cow slaughter) could not be correct because it is hardly conceivable that any Muslim would do such a thing in the middle of a huge Hindu fair. Probably, some mischief makers started this rumour.../

On October 13, 1967, a riot took place in Sursand that claimed 50 lives and led to the burning down of 400 houses.

Four years after Kripalani's death in Ahmedabad, there was yet another incident of communal violence in Sitamarhi and Riga in October 1992.

To the best of my knowledge, there has not been adequate research on Kripalani. It needs to be explored if he really made any significant intervention (inside Parliament or outside) on communal violence post-1947, particularly in Sitamarhi (which he represented between 1957 and 1962).

Or did he just forget the people who elected him? Did he share Patel's views on the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha? In his memoir, Kripalani is silent about the RSS and is almost sympathetic to the Hindu Mahasabha (page 154).

In an era when many Socialists and crypto-Socialists tend to switch over to hate-mongering ideologies, and the misguided youth of today are trying to build their quick political career by subscribing to divisive ideologies, they need to be persuaded to look upon rationally 'rebellious' and independent-thinking icons such as Kripalani, as much as the icons should be evaluated critically in academic as well as popular domains.

Professor Mohammad Sajjad, who is at the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University, is the author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours and Contesting Colonialism and Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur since 1857.