| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Building on the potential for closer ties is the changing narrative in each country about the other. The Chinese narrative on India has become significantly more positive over the past few years,' says Walter Andersen and Zhong Zhenming.

The new leadership in India and China are focused on ways to improve their economic collaboration and this goal will almost certainly set the tone of Prime Minister Modi's visit to China.

Both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping have put domestic economic development at the top of their country's respective policy agendas. They also appear to be leveraging their foreign policies to advance this common domestic goal.

Consequently, Modi and Xi seem to be consciously downplaying bilateral strategic tensions so as not to impede the advantages of economic cooperation.

Nonetheless, India and China are engaged in a complex hedging strategy regarding security issues that also includes the US and Japan.

India appears to be moving incrementally closer to the US and Japan to create a multi-centered balance of power in Asia. China for its part will probably seek to build closer economic links with India to counter these moves.

India and China have had a turbulent relationship in the past 65 years, including one full blown war, a couple of tense confrontations and a disputed boundary. In the early years of their relationship, however, the two sides worked cooperatively to decolonise Asia and New Delhi pushed to get the international community to deal with the Communist government in Beijing as the legitimate representative of China. But developments in the region (Tibet) and differences over colonial-era boundaries sent the Indo-China relationship into a tailspin that led to the 1962 war and some thirty years of tense relations after that.

This antagonism contributed to closer Chinese ties to Pakistan and closer Indian ties to the USSR. The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, combined with adoption of far-reaching market reforms by both countries, created a new strategic environment for India and China and opened up the possibility of better relations between them.

China and India, two populous and developing countries, face the similar task of maintaining high rates of economic growth to advance important socio-political goals like reducing high levels of poverty, creating employment for the millions who come into the job market each year, and enhancing popular support for their respective systems of government.

Prime Minister Modi advocates a development model similar to that of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping (1978 to 1989). Deng combined an emphasis on manufacturing to absorb his country's vast labor potential with huge investments in infrastructure to enable people and product to reach new markets. China's economic boom after the adoption of market reforms in the late 1970s transformed its economy.

Modi became well acquainted with the Chinese economic success story during his twelve years as chief minister of Gujarat (2002 to 2014), visiting China four times in that period and seeking Chinese investment and advice on development strategies.

After Modi became prime minister, President Xi Jinping during his September 2014 visit to India committed China to investing some 20 billion dollars over a five year period. The Chinese press reports that even more money will be committed to India during Modi's forthcoming visit.

Almost immediately after Modi's electoral triumph last year, the leadership of the US and Japan -- in addition to China -- moved quickly to establish contact with the new Indian prime minister, demonstrating that the political leaders in these countries view India as a major strategic player in Asia.

From India's perspective, good relations with these three countries make them more likely to refrain from taking steps that would undermine Indian economic and security interests. India thus has the option of moving closer to one or more of the other three as part of a hedging strategy.

An example is the nuclear deal worked out by the US and India between 2005 and 2008, which made a nuclear capable India an exception to the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty that had prohibited it from importing nuclear-related technology or material.

China was not enthusiastic about the exemption, but refrained from voting against it in the multinational Nuclear Suppliers Group rather than risk Indian and American ire. India, for its part, made plain to China and others that this deal did not alter India's foreign policy independence. In short, India would not align with the US against China.

In a broader sense, India and China have already committed to cooperate in many multilateral dimensions, such as collaborating in the BRICs Development Bank, the Asian International Infrastructure Bank, the UN Climate Change Conference, and the G20's discussion on international financial governance.

Since India is concerned by the growing Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean area, Modi's visit provides an opportunity for the two leaders to discuss practical ways to alleviate this competition. For example, the two sides are likely to consider ways to integrate the Chinese 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative with India's Mausam Project, the Cotton Route Plan and Spice Plan.

In order to reduce Indian concerns about China's military influence in the Indian Ocean, Beijing has also proposed establishing a trilateral cooperative partnership among China, India, and a third party such as Sri Lanka and Myanmar. However, the more serious security issue is the disputed border, which is far from being resolved as neither country seems willing to make the concessions that would satisfy the other side.

Perhaps the most that can be expected is that the two may seek ways to put in place improved confidence-building measures to forestall the kind of troop confrontation that took place last September on the first day of President Xi's trip to India and introduced an unexpected sour note during his visit.

The most significant aspect of the recent set of visits between the leaders of China and India is the determination of Modi and Xi to deepen the bilateral relationship even in the face of significant problems.

One sign of that commitment in the forthcoming Modi visit will be proposals to enhance people-to-people ties, reflected by the setting up of a Gandhi Centre at one of Shanghai's most prestigious universities and discussions to reshape the visa approval process.

Building on the potential for closer ties is the changing narrative in each country about the other. The Chinese narrative on India has become significantly more positive over the past few years. Modi in addition seems genuinely popular in China and his election was widely welcomed.

Only a few years ago, the Chinese narrative on India was that of a messy democracy that could not get much right. The new narrative on India is increasingly that of a partner with which to collaborate in addressing common Asian problems. While the narrative on China in India has been generally negative since the country’s military defeat in 1962, Modi's robust engagement with China may gradually change that perception if the two sides can work out mutually beneficial collaborative agreements.

Dr Walter Andersen is the Director, South Asia Studies, SAIS/Johns Hopkins University and a member of the International Relations Faculty at Tongji University, Shanghai. Dr Zhong Zhenming is a Visiting Research Fellow at SAIS/Johns Hopkins University and Associate Professor at Tongji University’s School of Political Science and International Relations, Shanghai.

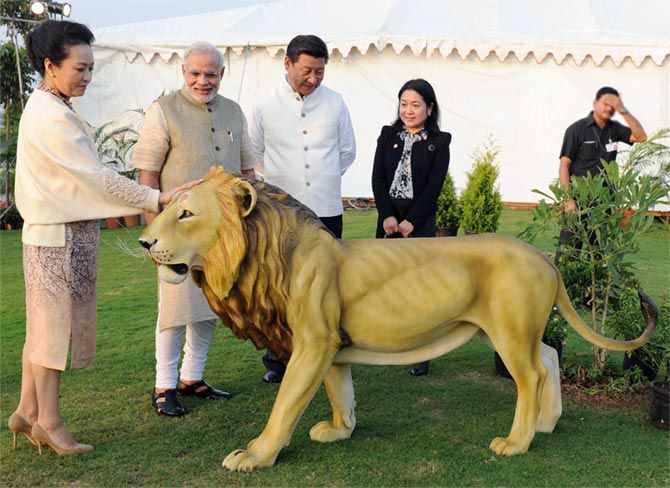

Image: China's First Lady Peng Liyuan, left, admires a statue of a Gir lion on the Sabarmati riverfront in Ahmedabad last September while her husband Chinese President Xi Jinping, third from left, and India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi look on. Photograph: Press Information Bureau