| « Back to article | Print this article |

'A class antagonism of rich versus poor took the colouring of a communal confrontation,' says Sunil Sethi.

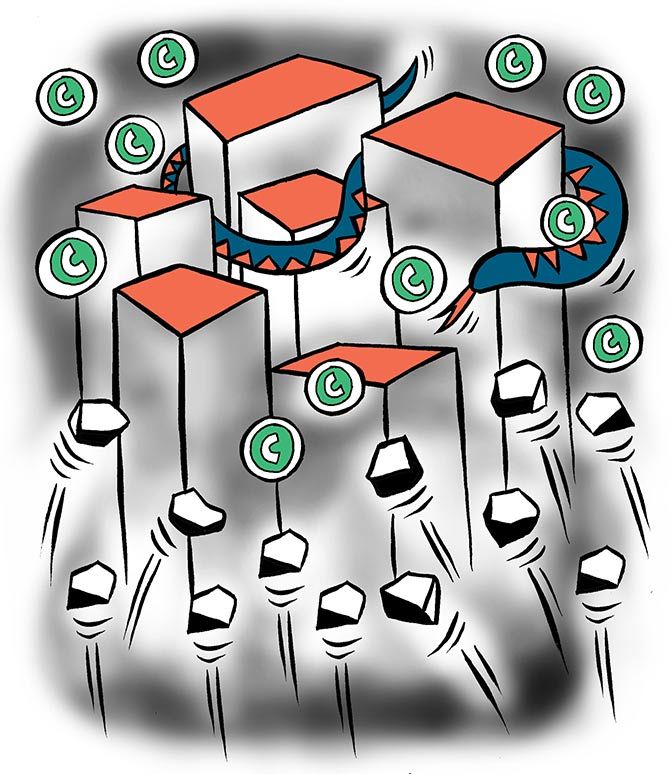

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

A small and ugly riot broke out in the capital's satellite city of Noida on July 12. A 26-year-old Muslim maid went missing from an apartment in a prosperous housing society.

When she did not return home to the nearby slum at night, a large crowd gathered and began stoning the building; its residents were expectedly terrified.

The dispute turned to be a nasty but not uncommon maalik-naukar (master-servant) row.

The maid's employers said she had stolen money and had footage to prove it; she accused them of unpaid wages and ill-treatment.

Meanwhile, conditions in the servants' settlement, as in many urban slums, were described as appaling -- a mass huddled in an insanitary, garbage-choked warren, living under tin roofs in the full pelt of the monsoon.

But an uglier subtext to the violence soon erupted.

Although the slum settlers are migrants from Cooch Behar (in West Bengal) their settlement is known as 'Bangladeshi colony'.

A series of provocative WhatsApp forwards and statements by residents' welfare associations (RWAs) on the 'terror of Bangladeshis in Noida' aggravated tensions.

Example: 'I would advise that all RWAs ban entry of Bangladeshi workers with immediate effect... they are encashing our need... and thinking it our weakness... (and) will all come down on their knees (sic).'

In short, a class antagonism of rich versus poor took the colouring of a communal confrontation.

Enmities of class, caste and creed have flared up in bigger, more virulent ways, from beef bans and lynchings of Muslims and Dalits to love jihads, but increasingly, the real and imagined politics of grievance finds expression in unexpected situations.

I got talking to a well-informed and articulate professional at a social occasion recently -- of the sort that right wing trolls label a 'libtard' -- and on being asked what she did, with good-humoured irony, she replied, "I'm a professional anti-nationalist you could say. I teach at Jawaharlal Nehru University."

Many a good professor is troubled, most notably Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, a documentary on whom has been held up by the censor board until the words 'cow', 'Gujarat', 'Hindutva view of India', etc are deleted.

The censor board chief Pahlaj Nihalani has done worse, from making B-grade films to doting music videos on Narendra Modi; evidently his Hindutva identikit of gau rakshak disallows anyone else from using the words.

The bitter twist of caste identities and grievance politics are best exemplified by the champion of social justice, Lalu Prasad, and his corrupt progeny, a 'Cricket XI' that beat the cricket control board for nefarious wheeling-dealing.

Cornered in a gigantic property scam of ill-begotten farm houses and real estate in Delhi and Patna, Bihar's (now deposed) deputy chief minister and former cricketer Tejashwi says he will go to the 'people's court' to seek legitimacy.

Like other icons of deprived classes such as Mayawati and Mulayam Singh Yadav, Bihar's Lalu Yadav family today stands for, in Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad’s withering phrase, 'the Robert Vadra model of development'.

Their aspirations are of princely proportion, their identities defined by social markers of untold wealth.

Ms Mayawati may strut around in diamonds to unleash a building mania for pleasure parks in B R Ambedkar's name to rival the Bourbon queens, but her political rivals in Uttar Pradesh are driven by a craze for foreign cars.

While Mulayam Singh and Akhilesh Yadav profess a preference for latest bullet-proof Mercedes models, younger son Prateek proudly posts images of his sky blue Rs 5 crore Lamborghini.

This flagrant exhibition of rapacity contributed to their defeat in the state election in the spring.

The noose of financial malfeasance is also tightening round Pakistani Premier Nawaz Sharif, as investigations into his family's huge hoard of hidden overseas assets are spotlighted.

Here is columnist F S Aijazuddin's writing in Dawn: 'One has only to turn the leaves of Pakistan's ledgers kept since 1947 to see how almost every ruler -- whether elected, nominated or self-appointed -- has in time blurred the distinction between State ownership and private possession...'

'The situation now is so chronic that... should Pakistan be headed by an honest leader, determined to cleanse the country of corruption, he would be hounded out of office soon enough for incompetence or unforgivable negligence.'

Like Mr Tejashwi, Mr Sharif is also mulling the idea of approaching the 'people's court'.

A general election is due next year, but will he call a snap poll to test his mandate?

As Mr Aijazuddin cynically remarks, 'Pakistani politicians could never become Roman Catholic priests. They refuse to take a vow of poverty.'

That fate, as in India, is reserved for the so-called Bangladeshi slum dwellers of Noida who took to stoning the apartments of their well-to-do employers.

The real injury of the aggrieved is not the same as the grievance politics of those in power.