| « Back to article | Print this article |

'A one party-State, with only one kind of Indian,' argues Mihir S Sharma.

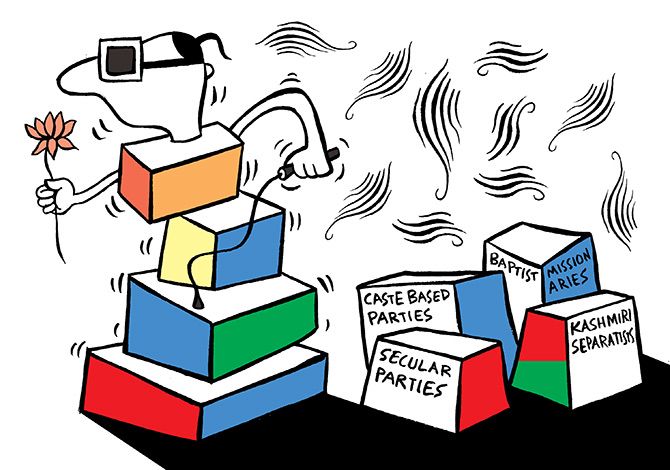

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The greatest rhetorical and ideological victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party and its parent organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, is this: It is now widely accepted, indeed viewed as an indisputable fact, that 'caste-based' politics is by definition bad.

This rhetorical victory might well sustain the BJP's winning streak going forward -- and keep its governments popular with the middle- and column-writing classes in spite of their evident failure to perform on the economic front.

This rhetorical victory was not inevitable.

You might argue that, with the example of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh before us, no Indian could conceivably think that caste assertion is a good idea for society at large.

But, on the other hand, I give you south India.

Karnataka invented the politics of mobilisation of Other Backward Classes or OBCs in the 1970s, and its development indicators have not exactly suffered, whatever Yogi Adityanath might want to go there and say.

As for Tamil Nadu -- a state that is a success story if ever there was one -- it accepted the politics of lower-caste assertion decades ago.

Meanwhile, the state with the least caste politics for decades was, as it happened, West Bengal -- and those decades are hardly the sort you would want to point to as an example for the country.

In other words, the notion that caste-based politics and lower-caste assertion is inherently dangerous, divisive, and bad for development is utter balderdash.

Caste-based politics succeeds and thrives for a reason: It allows members of hitherto deprived castes to recognise that they have a clear voice in governance; caste-based patronage helps fill in the gaps in India's notoriously leaky welfare system; and, for Dalits in particular -- as with many Muslims -- the primary issue that they vote on is one of law and order, of protection from intimidation and random violence.

Various forms of caste-based parties have a natural ability to respond to one or more of these questions, in varying degrees: Lalu Prasad might have focused on being the voice of Yadavs, the Dravidian parties on patronage, and Mayawati's Bahujan Samaj Party on law and order.

But this is by definition problematic for the politics of Hindu assertion.

For parties like the BJP, the basic structure that they wish for Indian politics is essentially a replication of older hierarchies: With people doing the tasks they are assigned by the 'natural' order.

In general, this is not a popular form of social or political organisation among those who have to do all the work.

Thus the movement to preserve and renew these hierarchies -- the essential task of the Sangh Parivar -- has to be concealed; and those who would seek to disrupt this order -- caste-based parties and those that give them succour -- have to be attacked.

This implies the near-panic that has taken over the BJP, the Sangh, and their online soldiers over the past six weeks.

Rahul Gandhi and the Congress are being accused of being dastardly and Machiavellian caste warriors (this would be the same Congress that a few weeks ago was pleading with the Gujarat electorate to see Gandhi as a 'janeu-dhari Brahmin').

Why? Because they stitched together a caste coalition in Gujarat that was enough for them to claim 'moral victory'.

And now because of the unprecedented sight of Dalits marching in righteous anger through the streets of Mumbai.

For the Sangh Parivar, any form of diversity and contestation is a threat, because the only form of social organisation it recognises is a unitary India with a Brahmin from Nagpur at the top.

When the Sangh says it is okay with Indian Muslims as long as they recognise their essential Hinduness, that is what they mean: That Muslims and other minorities need to recognise their place in the natural order -- an order which is very far from being flat.

'Secular' politics -- a politics organised around ensuring, first of all, that minorities of various kinds feel safe in this country -- is the biggest threat to this world view.

Any such concern indicates to the Hindutva right that 'India' is not a single unit.

There is no difference, to their mind, between caste-based parties, 'secular' parties, Baptist missionaries and Kashmiri separatists.

All seek to 'break India' -- an actual term that is increasingly used by the Indian far right.

In other words, the notion that multiple such groups want a sense of equality, voice and presence in a diverse polity is practically treasonous from the Sangh Parivar's point of view.

What is extraordinary is this basic, anti-politics, anti-diversity, and irrational view of India has been transformed into the basic assumption of Indian politics today.

An explanation of the sleight of hand by which this has been performed will have to wait for another day: But suffice it to say that the word 'governance' has been twisted to mean middle-class, upper-caste populism.

That is why the BJP's online warriors today will declare that listening to the Dalit voices in Mumbai is dangerous, populist, even treasonous.

If no secular or lower-caste party or movement can be truly 'Indian', then there's only one force left: The BJP.

And that's exactly what they want: A one party-State, with only one kind of Indian.