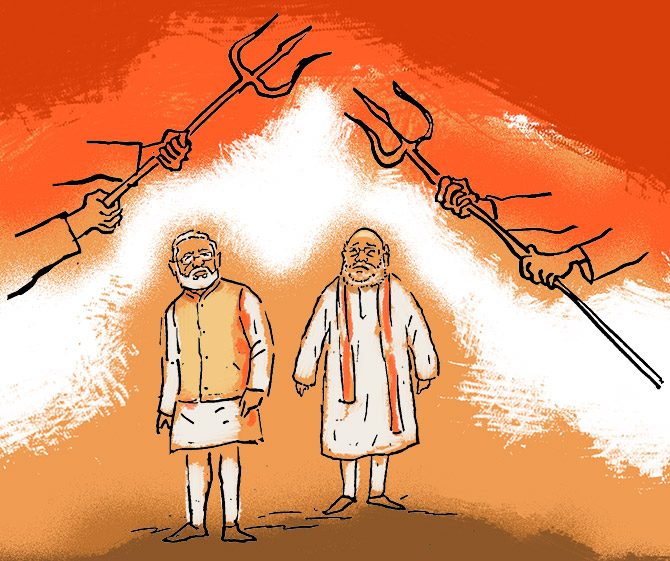

'Since the rise of the Modi-Shah paradigm, the BJP has followed a simple formula.'

'Sweep the Hindi heartland and the two big Western states, and you can rule India with a majority by just adding some little bits on the platter from here and there,' points out Shekhar Gupta.

Like the proverbial 'half-full or half-empty' glass, you can look at the much-discussed India Today group graphic showing the comparative swathes of saffron on the political map of India between 2017 and now.

At first glance, the graphic tells you that the BJP's reign over Indian states has declined from 71% to 40% in these two years -- just when you thought the party had reached its peak of popularity and unassailable domination under Narendra Damodardas Modi.

This, however, is the 'half-empty' perspective.

The half-full view is: Draw a similar map with the Lok Sabha results of last May.

What it would show is the dominant political reality: That in all of the north, the Hindi heartland, most of the coastal west and large parts of the east/north east, the BJP reigns unchallenged.

A fresh general election may not have an outcome very different from May 2019.

So, what are Mr Modi's critics celebrating?

Political reality, however, is complex and multi-layered, and comes in many shades of saffron.

Let's try lifting these layers:

Mr Modi, though a colossus in his own right, is no Indira Gandhi. Or, the other way of seeing it: The Indian voter has matured from the Indira era. She makes a clear distinction between voting choices for the Lok Sabha and the Vidhan Sabha.

Just like Indira, therefore, Mr Modi can still swing a 'lamp-post' election (where a leader can get people to vote for even a lamp-post on his ticket), but only for the Lok Sabha, when seeking votes for himself.

Unlike Indira, he cannot repeat the same magic for assemblies.

Maharashtra is a slightly complicated case and we will return to it.

Think Haryana.

Within five months of the Lok Sabha election, the party's vote share fell by a neat 22 percentage points, to 36% from 58%, leaving it well short of a majority instead of the widely predicted near clean-sweep.

This, in a state with a deep military and nationalist tradition, an insignificant minority vote, and 11 weeks after the action on Article 370.

Now, check the data backwards.

Even after the sweep of 2014, Mr Modi wasn't often able to sweep a state except Uttar Pradesh in 2017 and smaller states such as Haryana, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Assam.

But there also was the debacle of Delhi in 2015 first, and Punjab subsequently.

Gujarat (2017), which he should have won en passant, became a near-thing and stretched him fully.

In Karnataka, despite the anti-incumbency factor against the Congress and the embarrassing compromises it made with the Ballary brothers, the BJP finished well short.

Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh were lost later.

Now flip these numbers.

In each one of the states (barring Punjab) that the BJP lost or failed to win decisively, it swept the Lok Sabha polls.

Even in Delhi, Rajasthan, MP, and Chhattisgarh, where it had just lost to the AAP and the Congress.

Let's see what follows.

The most important takeaway is that, unlike in the Indira era, when one-party domination was accepted as a given, India has evolved into a much more federal nation. If the voter makes a clear distinction between choices made for the Lok Sabha and the Vidhan Sabha, it emboldens those who can hold their own, even if they aren't too hostile to the BJP, like Naveen Patnaik, K Chandrashekar Rao, Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy and, going ahead, probably the DMK.

It gives its adversaries, like Arvind Kejriwal and Mamata Banerjee, heart.

Her three by-election victories, including two by landslide margins six months after she struggled in the Lok Sabha election, underline the same voter discretion.

The third type of regional leader who'd smile is the BJP's own partner.

On the top of this list is Nitish Kumar -- remember, Bihar goes to the polls next year.

But even Prafulla Kumar Mahanta in Assam might revive his opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Bill, and Dushyant Chautala can aspire to punch at a level above his 'weight' category.

Here is why even the count of 17 states currently under the BJP, as the graphic shows, is a half-truth. Some of these, notably Bihar and Haryana, are in partnership with allies who might have a radically different ideological view and vested interests.

Some, like Meghalaya, Nagaland and Manipur, are essentially the political equivalent of leveraged buyouts. So, they aren't particularly BJP states.

Sikkim, Mizoram are part of the NDA, but not the BJP's.

The other, even less convenient unstated half of this truth is that today the BJP owns only three major states: Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, and Karnataka. The last one is fragile.

Since the rise of the Modi-Shah paradigm, the BJP has followed a simple formula. Sweep the Hindi heartland and the two big Western states, and you can rule India with a majority by just adding some little bits on the platter from here and there.

If this cannot be replicated in the states, you are stuck with federalism.

It means having to negotiate with chief ministers, accept some give-and-take, and live with the reality that hostile states will control their own police and law and order, and may even (like Ms Banerjee), refuse to carry forward your grand plans, even good ones like Ayushman Bharat.

They can no longer be ordered around.

You have to treat them with respect and deference, sometimes as equals.

This requires a radical change in method and style.

Because, 'cooperative federalism' that the prime minister often talks about is no longer a mere mantra, but an imperative.

But why did the Shiv Sena break away? It was because they saw in the relentless expansion of the BJP in their state a rapid erosion of their own ideological space. Their rebellion is a straightforward immune reaction to single-party domination, even if it is like-minded.

The Centre-state equation is more likely to return closer to the 25-year epoch of 1989-2014 now.

The noises from Maharashtra are disconcerting: Opposition to bullet train, silly threats on the metro.

Andhra has already delivered a nasty blow to India's FDI-friendly claims by peremptorily throwing out Amaravati and reputed foreign partners, from Singapore to the Gulf's LuLu Group.

The prime minister will have to reach out and hug these chief ministers too as he does his foreign counterparts.

And the biggest issue of them all: The National Register of Citizens, or NRC.

Ms Banerjee might have been the first to reject it formally, but it is unlikely that most of the non-BJP governments would now fall in line with an idea so divisive, so dangerous, and loaded against them.

The smaller Northeastern states have to deal with their own public opinion, which is hostile to the Citizenship Amendment Bill.

In terms of implementability, the NRC is therefore dead on arrival.

It may (and likely will) continue as a communally polarising concept for electoral reasons, a bit like the Ram temple might have been in the past three decades.

But it won't happen, definitely not as an NRC-CAB combo.

And finally, in case you think I am counting only the downsides for the BJP. See that graphic again, with shrinking swathes of saffron. That is a limited electoral reality.

Check out the ideological/philosophical picture. In all of India, you do not find one chief minister who, forget opposing, doesn't instead welcome the blunting of Article 370 and the Supreme Court judgment on Ayodhya.

Over the past decades, these were the favourite BJP/RSS issues that polarised Indian politics.

Now, a consensus similar to Kashmir and the Ram temple is building even on the Uniform Civil Code.

Even the Left Front government in Kerala wouldn't dare implement the Supreme Court order on Sabarimala.

Rahul Gandhi flaunts his janeu, temple visits, and high Brahmin gotra.

Whatever the political shades on the map of India, it is now dyed-in-saffron as far as the key RSS/BJP ideas are concerned.

The RSS, if not the BJP, could easily declare victory now.

Hedgewar, Golwalkar, and Savarkar will agree.

In special arrangement with The Print