| « Back to article | Print this article |

If the Indian Railways thinks it can get away with this sassy attitude, it is because it is, in a sense, a monopolist in the business of transporting people. The distances one has to cover, say from Thane or Virar to Mumbai is impossible by road provides railways the arrogance, says Mahesh Vijapurkar.

If the Indian Railways thinks it can get away with this sassy attitude, it is because it is, in a sense, a monopolist in the business of transporting people. The distances one has to cover, say from Thane or Virar to Mumbai is impossible by road provides railways the arrogance, says Mahesh Vijapurkar.

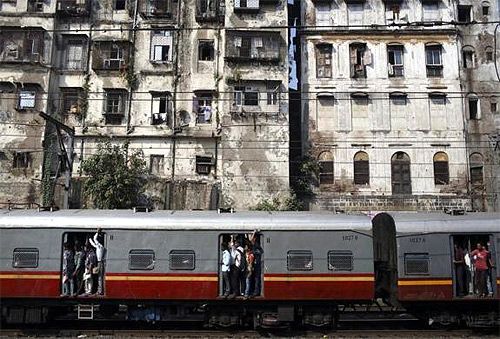

When 7.5 million passengers use the Mumbai’s suburban railway system, and the prices of season tickets are hiked to levels which almost takes away the subsidy component, it is a huge crisis for the commuters. It cannot be seen only from one angle -- making the railways avoid losses. That would be a one-sided perspective.

Not surprisingly Mumbai’s commuters are seething in anger and also know that it would be rolled back, if rolled back it would be, only because of political compulsions. That would be when the ruling alliance in New Delhi realises that Mumbai which was favourable to it in the Lok Sabha elections would turn away in the October assembly polls.

Such rollbacks -- this is a nursed illusion because Narendra Modi’s ‘bitter medicine’ caveat to revive the economy -- have to be on economic considerations. How important is the Mumbai suburban network which brings men and women to their workplaces and younger ones to schools and colleges, to the economy? Does ‘cheap’ travel add value or not?

Commuter trains being Mumbai’s lifeline -- or its entire metro region, nine times larger than the city itself -- was ignored when the choice to up the ticket fares was made. The affordability of the raised fares to the commuters has been stressed by citing a study that shows only three to five per cent of commuters cannot bear the new ticket prices.

Of the all passengers transported by Indian Railways, over half are on the suburban system in the country, and of that, over 80 per cent are said to be on the Mumbai network alone. When such a size is involved, it is expected that two things are considered: the use of the system to keep the economy running, and the impact on the personal economy of the users.

He is forced to pay Rs 550 instead of Rs 335 season ticket to go from Panvel, Rs 715 instead of Rs 355 from Karjat, and the multiples for the first class are worse. When Mumbai Rail Vikas Corporation itself says 68 per cent of them earn between Rs 5,000 and Rs 20,000 per month, you can estimate the burden in inflationary times.

Some 18 per cent are in the ‘no income’ category comprising mainly students and housewives, translating to burdens on the breadwinners who earn less than Rs 20,000. The curious thing is the survey findings were received by the MRVC only last week, which underscores the point: the economics of the users was never the consideration while hiking fares.

A commuter on Mumbai’s local train cannot be stereotyped as rich or poor, or with or without the ability to afford the new fares. They are as varied as the entire city’s population is, and farther from South Mumbai one lives, lower the economic status of the man. He pays high prices for poor real estate, sends children to private schools because government has opted out of even superintending the fees, and deals with medicare that cheats.

He pays higher costs too to keep the economy running. The long hours on the train because of the linear nature of the system, the consequence of not being able to find quality time of a duration worth a mention with the family, leave alone involvement in community activity, robs him or her of a valuable need. These have to be set off by the larger economy they help feed.

Long distance travel, which can be elective, and most often is, and the short -- if travelling nearly 100 km from Karjat, Kasara and Boisar is short distance every day, strap-hanging, forced to smell co-commuters’ armpits, feel molested all the way bodies touching -- distance daily compulsion just cannot be equated. It is not as if a corporate is spending on an AC first class to send someone by the Rajdhani Express to Delhi and pass on the costs to customers.

The commuters’ worth is realised by the bean counters only when the trains are stopped to prevent them reaching workplaces on bandh days. The loss to the economy per day, even if it is only back of the envelop calculation is trotted out each time. If keeping people moving to keep the businesses of Mumbai -- be it formal or informal running -- then Rs 300 crore is small change.

The official way of counting the pennies by ignoring the pounds is short-sighted, especially when the system that claims now higher costs from the commuters. They do not have proper stations, nor are the trains in their numbers anywhere being adequate, and the supply is too far behind the demand curve. It cannot be that they pay to get the services; it just doesn’t happen. This justifies the outcry against the higher levies.

If the Indian Railways thinks it can get away with this sassy attitude, it is because it is, in a sense, a monopolist in the business of transporting people. Poor management of road systems and road transport which force people to share three-wheelers and taxis driven by rude people gives the railways their attitude. The distances one has to cover, say from Thane or Virar to Mumbai is impossible by road provides railways the arrogance.