| « Back to article | Print this article |

'What gives hope is that Modi's own leadership is vitally linked to his capacity to deliver on the economic front. Indeed, if he succeeds, India's foreign policies will have changed beyond recognition,' feels Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar.

'What gives hope is that Modi's own leadership is vitally linked to his capacity to deliver on the economic front. Indeed, if he succeeds, India's foreign policies will have changed beyond recognition,' feels Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar.

The widespread expectation in India and abroad had been that the government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi would maintain 'continuity' in India's foreign policy.

As recently as end-July, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj affirmed, 'We think that foreign policy is in continuity. Foreign policy does not change with the change in the government.'

Indeed, India's political culture seldom admits abrupt policy shifts. Maturity and sobriety are synonymous with continuity.

However, one hundred days into the Modi government, it is becoming impossible to maintain the facade. Navigating through three high-level exchanges in rapid succession through September -- with Japan, China and the United States -- Modi is casting away rather summarily the lingering pretensions as if dead leaves in an autumnal month.

Modi's compulsive innovation is self-evident. Some of it may be organic, seasonal, locally sourced and even ethnically produced, but the pride in making the events stand out from the past is unmistakable -- such as the stunning decision to receive Chinese President Xi Jinping at Ahmedabad airport.

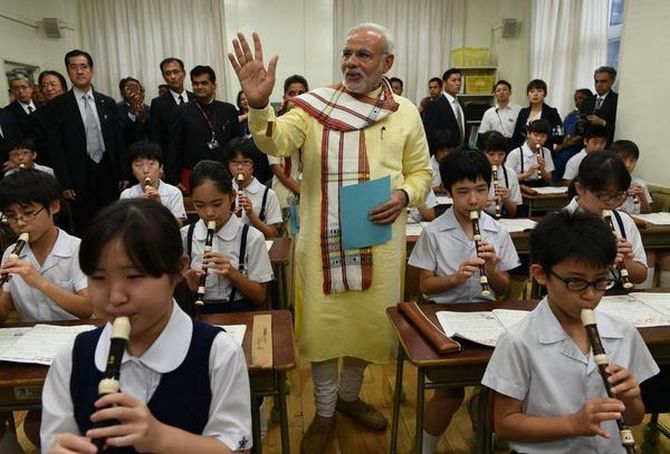

Image, above: Prime Minister Narendra Modi interacts with students at the Taimei Elementary School, in Tokyo. Photograph: The Prime Minister's Office

It seems those who spoke about 'continuity' didn't know Modi's mind while he himself has not cared to present a doctrinaire foreign policy.

But then, this is still work in progress. Modi inherits the anchor sheets of India's foreign policy -- primacy on economic diplomacy and strategic autonomy.

On the other hand, there has been a discernible shift in deploying strategic autonomy no longer as a 'stand-alone' pillar but as purposive underpinning for economic diplomacy.

Second, Modi has relocated the locus of economic diplomacy away from the West to Asia. This needs some explanation.

The heart of the matter is that there had been a pronounced 'militarisation' of India's strategic outlook through the past 10, 15 years, which was a period of high growth in the economy that seemed to last forever.

In those halcyon days, geopolitics took over strategic discourses and pundits reveled in notions of India's joint responsibility with the United States, the sole superpower, to secure the global commons and the 'Indo-Pacific'.

The underlying sense of rivalry with China -- couched in diplomatic idiom as 'cooperation-cum-competition' -- was barely hidden.

Then came the financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2008 that exposed real weaknesses in the Western economic and political models and cast misgivings about their long-term potential.

Indeed, not only did the financial crisis showcase that China and other emerging economies could weather the storm better than Western developed economies but were actually thriving.

The emerging market economies such as India, Brazil or Indonesia began to look at China with renewed interest, tinged with an element of envy.

Suffice to say, there has been an erosion of confidence in the Western system. From a security-standpoint, this slowed down the India-US 'strategic partnership.'

The blame for stagnation has been unfairly put on the shoulders of a 'distracted' and dispirited Barack Obama administration and a 'timid' and unimaginative Manmohan Singh government.

Whereas, what happened was something long-term -- the ideology prevalent in India during much of the United Progressive Alliance rule, namely, that the Western style institutions and governments are the key to development in emerging economies, itself got fundamentally tarnished.

What we in India overlook is that the 2008 financial crisis has also been a crisis of the Western style democracy. There has been a breakdown of faith in the Western economic and political models.

In the Indian context, the growing dysfunction of governance, widening disparity in income and the rising youth unemployment combined to create a sense of gloom and drift as to what democracy can offer and it in turn galvanised the demand for change.

Curiously, through all this, it became evident that the mixed economies and 'non-democratic' political systems weathered the storm far better. Indeed, Modi visited China no less than four times during this period.

Something also needs to be said in this backdrop about Modi's intriguing political personality. He is not really the one-dimensional man that he is made out to be.

The mismatch between image and reality is creating problems for his detractors and acolytes alike in this past 100-day period of his stewardship. And as time passes, it may become increasingly difficult to demonise him, or to perform liturgical rites to this celebrant.

Modi's non-elitist social background, his intimate familiarity with the ugliness and humiliation of poverty and ignorance, his intuitive knowledge of the Indian people and, above all, his keen sense of destiny ('God chooses certain people to do the difficult work. I believe God has chosen me for this work.') -- all this comes into play here, setting him apart from his predecessors in India's ruling elite.

By no means was it accidental that he highlighted human dignity as a vector of development in his famous Independence Day speech in New Delhi on August 15.

Nor is it to be overlooked that his emphasis is on attracting as much foreign investment as possible for projects that could create large-scale job opportunities for the people while pointedly ignoring WalMart as a pilot project.

In sum, Modi visualises Asian partners to be much more meaningful interlocutors at this point in time for meeting India's needs. Modi believes what he said in Tokyo recently, 'If the 21st century is an Asian century, then Asia's future direction will shape the destiny of the world.'

China has shrewdly assessed Modi's national priorities and sees in them a window of opportunity to transform the relationship with India into one of genuine partnership. Japan stalks China wherever the latter goes, but its actual capacity to match China is in serious doubt.

Also, in the ultimate analysis, Japanese businessmen go only when conditions are perfect -- unlike his Chinese or South Korean counterparts.

As for the US and the European countries, they are yet to figure out a way to catch Modi's attention span. In any case, the Western economies are still on recovery path and their interest in the Indian market has traditionally devolved upon boosting their own civil or military exports, rather than help India build its manufacturing industry or develop its infrastructure.

In sum, neither the Western countries nor Japan can hope to match the scale of involvement that China is offering -- setting up industrial parks, making the creaking Indian railway system work and so on. The Chinese offer to invest $50 billion in the first instance for the upgrade of the Indian Railways speaks for itself.

Put differently, Modi has redefined India's strategic autonomy. In the changed circumstances, strategic autonomy goes far beyond a matter of India's aversion toward 'bloc mentality' or, specifically speaking, its diffidence in the authenticity and sustainability of the US' rebalance strategy in Asia.

It may seem a paradox but under Modi, strategic autonomy presents itself as the key underpinning to create a level playing field for India's partnership with China.

Make no mistake, the opening up of sensitive sectors like the railways or ports for the Chinese companies demands a certain security mindset and Modi is surely taking a leap of faith.

The best outcome will be that as India and China get engaged deeply and extensively, they realise that they indeed have so very much in common by way of shared interest while clawing their way up on the greasy pole of the world order, where the lessons of history amply testify that established powers do not easily concede space to newcomers.

On the other hand, an irreducible minimum would also be that India and China settle pragmatically for maintaining peace and tranquility at all costs on their disputed borders without which a smooth and steady expansion of fruitful cooperation becomes problematic.

Therefore, Modi is justified in calculating that either way India is a net beneficiary in this historic gambit to break fresh ground with China. It is, actually, a 'win-win' gambit.

Therefore, Modi is justified in calculating that either way India is a net beneficiary in this historic gambit to break fresh ground with China. It is, actually, a 'win-win' gambit.

Image: Prime Minister Narendra Modi watches Russia's President Vladimir Putin shake hands with China's President Xi Jinping at the BRICS Summit in Fortaleza. Photographs: Paulo Whitaker/Reuters

To be sure, there are obstacles. The Indian bureaucracy, the defence and security establishment, right wing nationalists and a public weaned on official propaganda regarding the border dispute – these constituents look startled and disoriented.

But then, on India's political horizon if there is any leader who can force-march them it is only Modi who can. What gives hope is that Modi's own leadership is vitally linked to his capacity to deliver on the economic front.

Indeed, if he succeeds, India's foreign policies will have changed beyond recognition. The new stirrings already speculate on a border settlement with China in a conceivable future. Up until four months ago, this would have seemed audacious, given that the border dispute is a highly complicated backlog of past and current history. Bold ideas are often born that way.

Evidently, all this will not mean that history has ended. The Indian and Chinese models of development will forever present a fascinating study in comparison and contrast. The modernisation of India's military can be trusted to remain a continuing priority even if the country faces no danger of external aggression.

Equally, India will continue to diversify its external relations and will not put all its eggs in the Chinese basket in the Asia-Pacific. Most certainly, India's belief that it has a leadership role to play in its region is not going to be bartered away.

However, the bottom line is that these templates of foreign policy could become truly relevant only if the country got rid of the curse of poverty. India's influence in the region and its standing as a global player would ultimately depend on its comprehensive national strength and the example it sets as a peace-loving emerging power by creating a just and fair society.

Thus, through a corridor of time spanning a decade or two at any rate, the development agenda should get unquestioned primacy. This is where Modi is far-sighted in reorienting India's foreign policy.

M K Bhadrakumar is a former ambassador.